- In brief know about

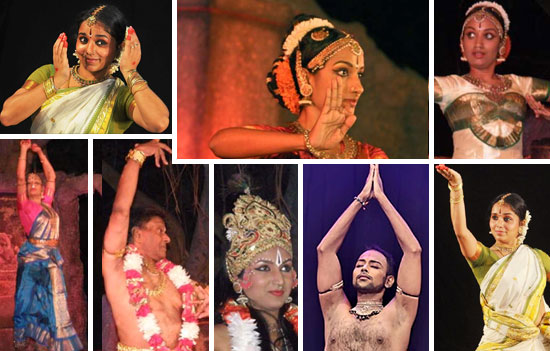

individual classical art forms i.e. Mohiniyattam,

Bharatanatyam, Kuchipudi, Koodiyattam and Kathakali etc.

India has her own classical artistic traditions,

particularly in the realm of visual art forms. The foundation of our culture is

rooted in the four Vedas: Rig, Yajur, Sama and Atharva Vedas which are composed

in Sanskrit, a language difficult for the common man to comprehend. According

to the legend the gods implored Brahma, the creator to provide a more

accessible Veda for humanity.

Moved by their request, Brahma instructed sage Bharata to

compose a fifth Veda in a simpler language. Bharatamuni extracted the essence of the Vedas and crafted the Natyashastra, infusing it with poetry from the Rig Veda theatrical

skills from the Yajur Veda, music from the Sama Veda, and the concept of rasa (emotional

essence) from the Atharva Veda.

This article was

first published in the Bhavan Journal.

Hailed as the ultimate authority on dance and drama, the Natyashastra comprises 37 chapters

imparting knowledge on various aspects of dramatic art and music. It elaborates

on literary devices such as simile, metaphor, and pun, while expounding on the

ten qualities (guna) of poetry and

identifying its dosha (flaws).

Eminent critics like Mitraguptan, Harshavardhan,Shankukan, Udhbhattan, Bhatanayakan, and Abhinavaguptan have contributed extensive commentaries on the Natyashastra. Among these only Abhinavaguptan’s Abhinam Bharati has survived through the ages.

In Vikramorvasiyam, the second of the three plays written by Kalidasa (the first and third being Malavikagnimitram and Abhijnanasakuntalam) he alludes to sage Bharata, as one who trained the devas or Gods in the art of dramatics. The term ‘Margi’ signifies the classical visual art traditions upheld by the Natyashastra transcending regional and temporal boundaries. ‘Desi’ refers to the regional and folk-art forms, such as Padayani, Mudiyattam, Velakali, Theyyam, and Theeyaattam, which are deeply ingrained in India’s diverse cultural landscape.

Margi, the national network of performing art forms evolved embracing the

regional art forms nascent to Kerala. Though visual art forms like Koodiyattam,

Kathakali, Mohiniyattam, Bharatanatyam, Kuchipudi are essentially based on the

principles of Natyashastra, the heritage of Kerala is

embedded in them.

Our Temple Art Forms

The temple and its precincts have long been the fount of

our classical art forms. These art forms are intricately linked to rituals, with

bhakti (devotion) as the spiritual foundation. Temple festivals, or Ulsavams, showcase a rich tapestry of

cultural expressions, including Panchavadyam

(orchestra of five instruments), Pandimelan

(classical percussion concert), Ezhunnallathu

(processions), Deepalankaram (lamp illuminations),

Vedikettu (fireworks), and performances of Kathakali, Koodiyattam, Koothu, Thullal, and various cultural fairs. Even monumental sculptures stand as testaments to India’s artistic and spiritual culture.

Mohiniyattam

Gods were fond of flowers and music. Women dedicated to

temple service, known as Devadasis, undertook

various devotional duties, including cleaning, garland making, singing, and

dancing to appease the deities. Self-ordained men would appease the almighty

with songs and music. They were known as Bhagavatar

or one who is close to the lord. Gradually music was extolled to the level of

being the language of gods. Music took its place in temple sopanam or steps and dance took to the front portals of the temple.

It is believed that these danseuses were the successors of Urvasi the celestial

dancer in the court of Lord Indra.

Over time, this devotional dance evolved into Mohiniyattam, Kerala’s own classical dance form. Mohini means one who rouses desire. Most of the compositions of Swathi Thirunal and Irayimman Thampi have been presented in the form of Mohiniyattam.

Bharatanatyam

Kerala’s Mohiniyattam shares several similarities with Tamil Nadu’s Bharatanatyam. ‘Bharatanatyam’ is short for Bhava (expression), Raga (melody), and Thala (rhythm). It adheres to the principles of the Natyashastra of sage Bharata. Bharatanatyam was further refined by eminent artistes like Krishnan Iyer, and Rukmini Devi Arundale. While Bharatanatyam originated in Tamil Nadu, it enjoys immense popularity in Kerala too.

Kuchipudi

This vibrant dance originated in the village of Kuchipudi in Andhra Pradesh’s Krishna district, where it was primarily patronised by the Brahmin community. Blending the elegance and poise of Bharatanatyam with the acrobatic agility of Odissi, Kuchipudi features dynamic movements, including dancing on the rims of brass plates and balancing water filled pots on the head. The rhythmic tunes of the mridangam, flute, violin and the guru’s syllabic mnemonics (verbal rhythm recitation) guiding the dancer’s footwork and movements are all synchronised to make this art form truly attractive.

Odissi dance.

Odissi dance.

Koodiyattam

This ancient Sanskrit theatre tradition, dating back over

2,000 years, finds its roots in the dramatic works of playwrights like Bhasan,

Sakthibhadran, and Mahendra Vikraman, who emphasised Angika Abhinaya (expressive body movements) in accordance with the

principles laid down by scholars. Mantrankam,

Anguliyankam, Mattavilasam, Thapti Savarnan were the texts selected for Koodiyattam. This art form that dates back to 2000 years, was recognised by the UNESCO in May 2001, as one of the ‘Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity’. This was largely due to the documentary on the artists of Margi by the internationally acclaimed filmmaker Padma Vibhushan Adoor Gopalakrishnan.

Koodiyattam for the Masses

Koodiyattam the art form was liberated from the confines

of the madom or homes of the Chakyars

by the efforts of Painkulam Rama Chakyar. He took the initiative to bring the

art form to the masses. In 1948 Painkulam Rama Chakyar performed the koothu in

an illam at Kottarakara. In 1952 he

performed Koodiyattam in Ganapath High school at Kozhikode. As a result, those

born outside the Chakyar community also got opportunities to learn the koothu

and Koodiyattam.

Had it not been for him, there would not have been great

performers like Padmasree Kalamandalam Shivan Namboothiri, Kalamandalam Girija,

Kalamandalam Shylaja, Margi Sathi and Margi Usha. In 1965 Koodiyattam kalaris were started in Kerala

Kalamandalam.

In 1975 Painkulam Rama Chakyar took a bold and revolutionary

step. Defying all norms and risking the penalty of being excommunicated, he

sailed across the seas. Under his leadership Koodiyattam was staged in Paris.

In 1981 the Koodiyattam kalari was

introduced in Margi at Thiruvananthapuram.

Padma Bhushan Ammannur Madhava Chakyar and Padmashri Kalamandalam

Krishnan Nair lighted the traditional lamp and inaugurated the kalari. Margi kalari is the only centre, south of Tripunithura

to impart training in Koodiyattam. Margi has produced artists like Margi

Narayanan, Margi Madhu, Margi Sathi, Margi Raman and Margi Usha.

Chakyar Koothu

This dance form is the elaborate presentation of the

tales from Ramayana, Mahabharata and the Upanishads. The vibrant language and

theatrical expressions of the performer in the guise of a clown are laced with

humour and wit.

Chakyars are famous for their skills in highlighting

contemporary issues, often pointing out the faults, shortcomings and lack of

concern of the dignitaries seated in the front rows in witty language.

Nangiarkoothu

An offshoot of Koodiyattam, Nangiarkoothu is an elaborate

dance-drama performed by Nangiars. It comprises an elaborate portrayal of

stories of Lord Krishna by Kalpalathika, the cheti or maid of Subhadra, Krishna’s sister. King Kulasekara Verman of the 11th century AD played a key role in legitimising this art form. He married a Nangiaramma, a woman renowned for her extraordinary beauty and linguistic prowess. However, their children faced excommunication from society. Heartbroken and indignant. Kulasekara Verman issued a royal decree commissioning the performance of Sri Krishna’s stories through Nangiarkoothu in temples.

He granted approval and allocated royal funds to support its propagation.

As a result, Nangiarkoothu gained immense acceptance and flourished as a revered

art form. Today this art form is open to all and is also a means of livelihood

for many women.

Shri Ramacharitham

Margi artist Sathi composed and choreographed the

Ramacharit (the story of Rama) as Nangiarkoothu adhering to principles of the

art form. This is her unique contribution.

Thullal

Following the Koothu, is the creation of Thullal, an art

form rich in wit and satire by Kunchath Nambiar. Legend has it that he fell asleep

while playing the Mizhavu drum during

a Chakyar Koothu performance in Ambalapuzha. The chakyar ridiculed him

seamlessly in a lucid and engaging language with abundant humour and wit.

Later Nambiar developed this lively and engaging art form and Thullal was born. It evolved into three distinct forms Ottan Thullal, Parayan Thullal, and Sheethankan Thullal—each distinguished by unique costumes and performance styles.

Kathakali

Kathakali is universally recognised as a complete art form, preserving its 500-year old threefold structure—Kottu (percussion), Paattu

(vocal music), and Aattam (expressive

dance and acting). This harmonious blend of melody, rhythm, and movement is

known as Thouryatrikam. The thuram or perumbara, an ensemble of

percussion instruments, dictates the rhythm and pace of the performance,

reinforcing the essence of thouryatrikam.

In Kathakali, the Aksharamala (alphabet) corresponds to its fundamental 24 mudras (hand gestures). These, combined with intricate eye movements and facial expressions, bring each word or padam to life. The ensemble of percussion instruments—Chenda, Aladdalam, Edakka, Chengila, and Ilathalam—complements the Aangika Abhinaya (expressive

gestures), making movements meaningful. The song explains the storyline. As the

performance unfolds, the narrative attains depth, while the dance reaches a

state of self-actualisation. In Kathakali, every movement is dance, rhythmic

dance.

Knowing the story beforehand allows the audience to fully

grasp the gestures and appreciate the performance. Female characters generally

do not require the Chenda, except for dark characters like Putana, where the

beat of the Chenda adds depth to the portrayal. No other dance form culminates

in such a grand crescendo, where a symphony of all instruments brings the

performance to a rhythmic climax. This unique quality makes Kathakali a dance

form revered worldwide.

Plot of Kathakali

Kathakali derives its themes from Puranic and historical

stories, particularly the Mahabharata, Ramayana, and Bhagavatam. The

Mahabharata, a vast repository of wisdom, serves as the foundation for many

dance narratives. Vyasa proclaimed upon completing the Mahabharata:

“What is found in this epic may be found elsewhere, but what is not found here will not be found anywhere else.” The Ramayana and Bhagavatam extensively chronicle the feats of Rama and Krishna, the 7th and 9th avatars of Lord Vishnu, respectively. These two divine figures are unique in that they performed numerous leelas (superhuman

exploits), forming the primary themes in Kathakali.

Special Features of Kathakali

Kathakali richly portrays otherworldly characters and

their extraordinary feats. Some examples are:

1. Ten-headed Ravana juggling Mount Kailasa.

2. Hanuman’s heroic journey across the sea to Lanka, discovering Sita, receiving her Chudamani (ornament), and setting Lanka ablaze on being captured by Ravana’s henchmen.

3. Ravana observing severe penance for obtaining four boons from Brahma. Brahma refusing to appear. Nine of his heads getting

severed and reduced to ashes. Brahma making his appearance and granting him the

boons when the sword is raised to sever his 10th head.

4. Epic battles featuring uprooted trees—between Bali and Sugreeva in the Ramayana and between Bhima and Bakaasura in the Mahabharata.

5. Slaying of Bali and Bakaasura—Bali being killed from behind by Rama in the battle between Bali and Sugreeva. Bheema killing Baka using his fist and tree stumps.

6. The shrewdness of Sri Krishna, who repeatedly uses strategy and

intelligence to protect the Pandavas.

Kathakali artists depict all these grand spectacles without props or elaborate stage settings. Without any external props, Kathakali relies solely on the actor’s expressions, movements, and gestures, to transport the audience into its mythical world. This is neither required nor is it possible for any other art form to communicate, in this manner.

For example, in Bali Vijayam, Narada, the narrator, stands alone on stage with the performer. During the Kailasodharanam (Ravana lifting Mount Kailasa), there is no actual mountain, no Pushpaka Vimana, no Shiva or Parvati—only the artist portraying the character of Ravana. Kathakali performances are almost cinematic in their storytelling.

Consider the depiction of Kailasodharanam. Ravana notices Mount Kailasa obstructing his path and commands it to move. When the mountain remains unmoved, he decides to uproot it. In that moment, Shiva seizes the opportunity while Parvati is away bathing, to release the Ganga and embrace her. Parvati unexpectedly returns and is furious to find Ganga in Shiva’s arms. Just as her anger reaches its peak, the mountain trembles due to Ravana’s act of lifting it. Overcome with fear Parvati seeks refuge in Shiva’s arms, forgetting her wrath. Shiva, realising Ravana has inadvertently saved him from a domestic quarrel, rewards him with the divine ‘Chandrahasa’ sword.

This entire sequence is enacted through gestures and Aangika Abhinaya, accompanied by

rhythmic music. The depth of expression ensures that even without dialogues or

props, an attentive audience can fully grasp the narrative. This unparalleled

scope for acting and expression is unique to Kathakali.

In Kathakali, every action becomes dance—be it a wedding, chariot ride, battle march, or war itself, all unfold within the rhythmic cycles (Thalas).

Music in Kathakali

Kathakali music (Sangeetham) is soulful, clear, and easy

to understand. The rhythmic cycle enhances the abhinaya, allowing it to delve

into deeper layers of meaning. The synchronised interplay of eyes, lips, facial

muscles, hand gestures, body movement and the final intense and laborious flourish, make Kathakali an art form unparalleled in its

grandeur and theatrical brilliance.

Author is Hon. Secretary, BVB,

Thiruvananthapuram Kendra.

This article was first published in the Bhavan’s Journal, June 16-20, 2025issue. This article is courtesy and copyright Bhavan’s Journal, Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, Mumbai-400007. eSamskriti has obtained permission from Bhavan’s Journal to share. Do subscribe to the Bhavan’s Journal – it is very good.

Pic of Kathak Dance of North India.

Pic of Kathak Dance of North India.

To read all

articles on Indian Dance Forms