-

The

word Mujra has negative connotations. It basically, means to bow down and pay

respect. So how did Mujra get negative connotations? Read on.

If one searches online the meaning of the word ‘Mujra’, the results that appear are: Urban dictionary - An erotic dance performed in front of a king or nobleman. Wikipedia

- A dance performed by a Tawaif that originated in India during the Mughal

rule. Some random results also say - Dance

by a prostitute. Even YouTube throws up some disturbing search results for

Mujra.

Most

people, if asked the meaning of Mujra, would give these answers. Well! These

meanings might not be grossly wrong but they are definitely inadequate and

result of a perception twisted by several factors, over many decades.

Mujra, basically, means to bow down and pay respect. In Marathi, salutations paid to a great personality are called ‘Manacha Mujra’ even now. In Uttar Pradesh, a folk Bhajan राम झरोखे बैठ के सबका मुजरा ले, जैसी जाकी चाकरी वैसा वाको दे (Ram jharokhe baith ke sabka mujra le, jaisi jaaki chakri vaisa vaako dey) is hugely popular. It means Bhagwan Ram watches through a Jharokha (window), accepts Mujra (salutations) from everyone and rewards them as per the intensity of their devotion.

The word Mujra here, clearly, doesn’t refer to any dance performance, erotic or otherwise. These Bhajan lines are also inscribed on the performance stage of the central lawn at the National Botanical Research Institute (NBRI), Lucknow.

It

was customary for dance performers to bow down and pay respects to God, their

Guru and the audience, before starting their performance. This tradition is still

alive in the form of Namaskar and Salaami tukdas/todas of Kathak. It was

probably this act of Mujra or paying respect that lent its name to the entire

performance. An example of the Kathak

Salaami can be seen in the Video

Under

the patronage of Nawab Wajid Ali Shah, the last king of Awadh, two Kathaks (Kathakars

or storytellers) Kalka Maharaj and Bindadeen Maharaj developed and refined the

classical dance form of Kathak. The Nawab learnt the form himself and is known

to be an able performer who often essayed the role of Krishna-Kanhaiya in the

Kathak recitals.

Kalka and Bindadin Maharaj established the Lucknow Gharana (Lucknow school) of Kathak and also trained the Tawaifs (courtesans) and Bhaands (entertainers) of the Awadh darbar in this performing art. Mujra was born from this very dance tradition.

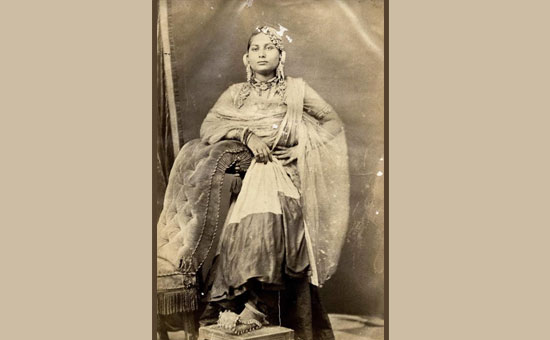

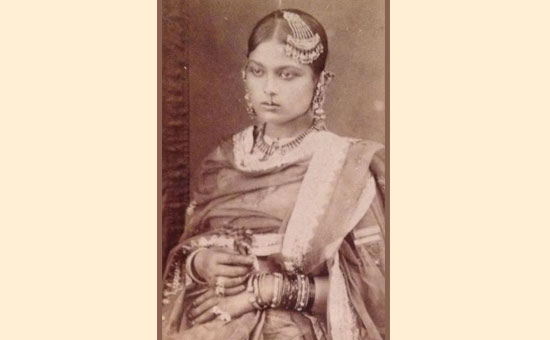

.jpg) Courtesans of Lucknow.

Courtesans of Lucknow.

The

commercial Indian cinema is guilty of misrepresenting the Mujra. However, a few

classic and art films like Mughal-e-Azam, Pakeezah and Umrao Jaan have

recreated some tasteful Mujras as well.

A film where the Mujra performance has been depicted with utmost authenticity is Shatranj ke Khiladi (1977), directed by the legendary director Satyajit Ray. The film shows a Mujra being performed for Nawab Wajid Ali Shah on the Thumri ‘Kanha mein tose haari.’ It was a composition of Bindadin Maharaj himself. Birju Maharaj, his descendant, rendered it vocally, for the film. Birju Maharaj’s disciple Saswati Sen performed the dance on it. The instruments used and also shown in the video, especially, Pakhawaj and Sarangi were authentic. So was the costume, the Awadhi Khada Pyjama and Peshwaz, worn by the dancer.

By

looking at this Video one can imagine what the real Mujras must have been like – Graceful, sophisticated and artistically invigorating.

The Ghazal ‘Inn aankhon ki masti ke’ from the film Umrao Jaan (1981) is more cinematic than realistic, but it definitely brings out the artistic flair and poise that Tawaifs had as performers. Viewing their musical performances was much like it is today, only the set-up used to be of a ‘Kotha’ (the residence of a courtesan) instead of an auditorium or amphitheatre. The other difference was that these events were not ticketed and a selected segment of the society had access to them. The director of the film, Muzaffar Ali, hails from an aristocratic family of Awadh.

Therefore,

he presented the nuances of the culture in which the Mujra was born, in the

most tasteful and refined manner. Set design of the Baithak (drawing room) of

the Kotha, the costumes and jewellery, the music, the poetry and the dance,

every detail was immaculate and exuded finesse. To see Video

The

word Tawaif has become synonymous with prostitute today but Tawaifs were

courtesans, much like the Geishas of Japan. They were respected culturists,

aesthetes, connoisseurs and entertainers. They were artists who thrived on

patronage from the royalty and aristocracy. It is common knowledge that princes

were sent to them to learn art appreciation and etiquettes.

Courtesans of Lucknow.

Courtesans of Lucknow.

There existed a hierarchy even among performers, there were Domnis, Miraasins, Paturias who were defined based on where they performed. Some of them were nomads and danced in public for commoners. Some visited homes to sing at ceremonies and celebrations. Some were rural while others were urban. Tawaifs were at the top of this hierarchy. This is an elaborate subject of research by itself. Author Prabhat Ranjan has touched upon it in his book ‘Kothagoi’ (Hindi). A systemic crushing of the Indian performing arts by colonial forces and their display of extreme prejudice by labelling all the performers as ‘Nautch girls’ became deeply rooted in the Indian psyche. As a result, the performing classes were further marginalised after India gained independence. These stereotypes were further perpetrated by the tone-deaf commercial cinema.

In early India, there were Ganikas and Veshyas. A Veshya was someone who traded sex for money but a Ganika was like a Tawaif, a performer. Ganikas and Tawaifs were respected but not accepted as a part of the society. The rigidly patriarchal system did not allow women to have a life outside the confines of a home.

Women who had a public life were considered ‘Baazaru’ (of the market) no matter how good they were as artists. The word Ganika (Gan+ika) literally means the one who belongs to the public (Gan). It was not possible for a woman to pursue arts and be a ‘family woman’ at the same time. If she chose to be an artist she inevitably became public property, even if she remained an artist and never took up prostitution.

In his book, ‘Yeh Kothewaliyan’ (Hindi), renowned author Amritlal Nagar has documented his in-depth research on this subject. The book also contains interviews of ‘Khandani’ Tawaifs of Lucknow and Benaras, that Nagar ji recorded personally.

Courtesans of Lucknow.

Courtesans of Lucknow.

Khaandani

Tawaifs were women whose family profession was entertainment and their

foremothers had been in it for generations. However, some laws (formed after

the Indian independence) and decline in patronage

led to the gradual extinction of their class. Some of them were also forced to

take up prostitution for survival.

Thereafter, the institution of Kotha was reduced to a brothel and Mujra became an erotic dance performance which was provocative and borderline vulgar. This was a terrible and irreparable loss for India’s indigenous performing arts, as a huge repertoire of songs and dance styles also vanished with their keepers.

Thankfully,

we are no longer this cruel to female dancers, musicians and artists. But we

still view female artists of the past with contempt. We might never be able to

use the words Tawaif and Mujra with respect, owing to the distortion that they

have gone through.

But it cannot be denied that Mujra in its true form was aesthetically much more evolved than the item numbers of today. It illustrated that entertainment doesn’t have to be crass or devoid of art.

There is a lot that the artists and entertainers of today can learn from the Tawaif and Mujra culture, as illustrated beautifully by Kathak dancer Manjari Chaturvedi in her performance ‘The Courtesan’. This performance is a part of a larger project aimed at busting myths about the Tawaifs and giving them the respect they deserved as keepers of tradition and culture. To see Video

All

pictures are taken by and courtesy photographer Darogha Abbas Ali, published in

a book called The Lucknow Album (1874). Copyright lies with them.

Author is from Lucknow. She is a Jewellery

Designer, runs www.desidrapes.wordpress.com

and lots more.

To read all

articles by author

References

1. Author’s personal experience of learning the basics of Kathak and folk culture of Uttar Pradesh.

2. Stage shows – Manjiri Chaturvedi’s dance drama ‘The Courtesan’, Lillete Dubey’s play ‘Gauhar Jaan’

3.

Yeh Kothewaliyan, Amritlal Nagar (Hindi)

4.

Kothagoi, Prabhat Ranjan (Hindi)

5. Chatterjee, Gayatri. “The Veshyā, the Ganika and the Tawaif: Representations of Prostitutes and Courtesans in Indian Language, Literature and Cinema.” Prostitution and Beyond: An Analysis of Sex Work in India. Eds. Rohini Sahni, V. K. Shankar and Hemant Apte. New Delhi: SAGE Publications India Pvt Ltd, 2008. 279-300. SAGE Knowledge

6. Ganikas in Early India: Its Genesis and

Dimensions by Monika

Saxena