- Article tells about the origins of Thangka paintings, types of paintings, favourite Gods depicted in Thangka, painting process, guidelines for aspiring artists and spiritual connection of Thangka paintings.

The

Origins of the Thangka

The

Tibetan Thangka is an art form that originated in Nepal, and was brought to

Tibet by Nepalese princess, Bhrikuti, who was the wife of Sonsgtsen Gampo,

the founder of the Tibetan Empire. The paintings were developed over the

centuries from the early wall murals that can be seen in a few remaining sites

like the Ajanta Caves in India and the Mogao Caves in Gansu Province, Tibet.

The

Mogao Caves have extensive wall paintings, and were previously a repository for

many Tibetan paintings on cloth, which are some of the earliest surviving

Thangka, as well as other manuscripts, paintings and prints. The earliest dated

prints from the “Library Cave” were dated to be from around 780-848 AD, when

the region was under Tibetan rule.

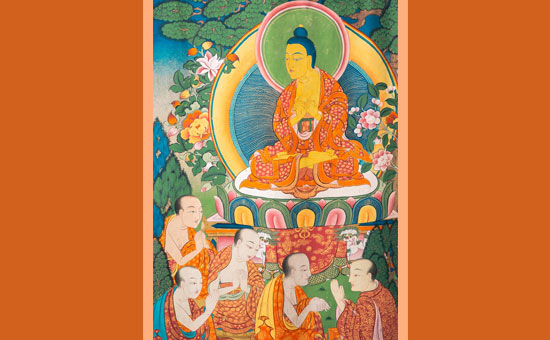

Traditionally,

the Thangka are designed to tell the life of

Buddha, as well as other influential lamas and deities. The Tibetan word

THANG KA means “recorded message” in English.

The

composition of the Thangka is very complex and elaborate, and often

incorporates the central figure - normally a deity - surrounded by many smaller

figures, in a symmetrical design.

Although

they are less common, narrative scenes are also depicted on Thangkas. Thangka

are also used as devotional pieces during religious rituals or ceremonies, and

can be used as a medium for prayer.

Moreover,

Thangkas can aid in the spiritual path to

enlightenment as the religious art is used as a meditation tool.

Devotees often have Thangka paintings hung in their homes, bedrooms and

offices.

Types of paintings

In

Tibet, religious paintings come in several forms, including wall

paintings, thangkas (sacred pictures that can be rolled up), and

miniatures for ritual purposes or for placement in household shrines.

Some

thangka artists travelled all over Tibet, working for monasteries as well as

for private patrons. Thangkas were

commissioned for many purposes - as aids to meditation, as requests for

long life, as tokens of thanksgiving for having recovered from illness, or in

order to accumulate merit.

Those

who commissioned thangkas also supplied the materials, so their

financial status determined the quality of the pigments, the amount of gold

used for embellishment, and the richness of the brocade on which the painting

was mounted.

Thangkas could be woven, embroidered, or appliquéd.

Special Thangkas

And

at the Shoton Festival, one of the most popular of Tibet’s traditional

festivals, the Thangka is unveiled at the Drepung Monastery in Lhasa.

As

the sound of the horn echoes through the valley, a host of lamas carry the huge

portrait of Qamba Buddha from the Coqen Hall and towards the western end of the

monastery to a specially erected platform. As smoke rises from all sides and

monks chant scriptures, the lamas slowly unroll the Thangka to cheers from the

crowds, who rush to the painting to offer their white hada, or prayer silks.

This Thangka is only open for around two hours, before the monks move it

carefully back inside for another year.

Favourite gods

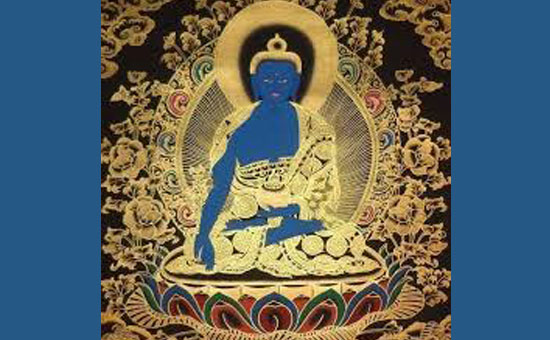

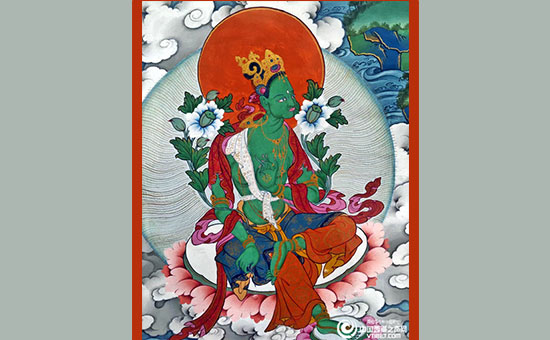

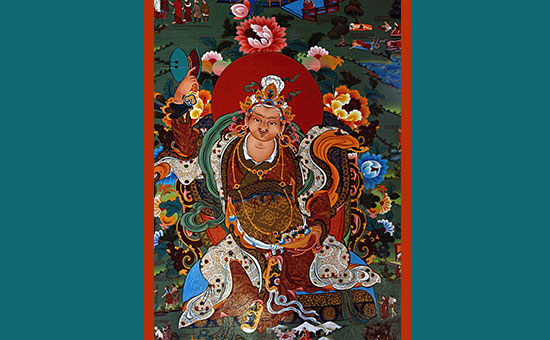

Peaceful

deities, wrathful deities, and mandalas are among the subjects depicted

in thangkas. Each Tibetan Buddhist sect has its favorite gods; therefore,

identifying a particular god depicted on a thangka helps determine the sect

with which the painting is associated. For example, a blue image of the Buddha

Samantabhadra situated at the top center of a thangka associates that

painting with the Nyingma order, and paintings made for the Gelug order usually

include a figure of TsongKhapa.

Thangkas

are fragile objects; they fade when exposed to light. The Asian Art Museum’s

policy is to preserve these objects by displaying them in low light and by

rotating the collection; happily, this will allow visitors to see a new group

of thangkas about every six months.

Painting Process

Traditionally,

thangka paintings are not only valued for their aesthetic beauty, but primarily

for their use as aids in meditational practices. Practitioners use

thangkas to develop a clear visualization of a particular deity,

strengthening their concentration, and forging a link between themselves

and the deity.

Historically,

thangkas were also used as teaching tools to convey the lives of various

masters. A teacher or lama would travel around giving talks on

dharma, carrying with him large thangka scrolls to illustrate

his stories.

The

deities shown in thangka paintings are usually depictions of visions

that appeared to great spiritual masters at moments of

realization, which were then recorded and incorporated into Buddhist

scripture.

The

proportions are considered sacred as not only are they

exact representations of Buddhist deities, but also the visual expression

of spiritual realizations that occurred at the time of a vision.

Thangka

painting is thus a two-dimensional medium illustrating a multi-dimensional

spiritual reality. Practitioners use thangkas as a sort of road map to

guide them to the original insight of the master. This map must be accurate. Hence,

it is the sole responsibility of the artist to make sure that the Thangka

Painting is considered genuine and guides one and all to the proper and

peaceful place.

Because

thangkas are not the product of an artist’s imagination, but are as carefully

executed as a blueprint drawing, the role of the artist is somewhat different

than the inventor we know him to be in the West. The role of the artist becomes

one of a medium or channel, who rises above his own mundane consciousness to

bring a higher truth into this world. In order to ensure that this truth

remains intact, he must diligently adhere to all the correct guidelines.

Guidelines for Aspiring Artists

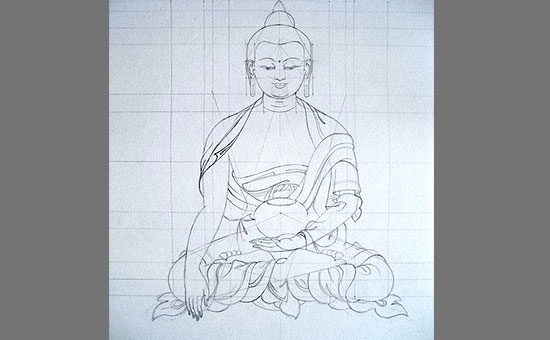

Aspiring

thangka artists must spend years studying the iconongraphic grids and

proportions of different deities and then master the technique of mixing and

applying mineral pigments.

Norbulingka

Institute in Dharamshala, Himachal Pradesh offers a three-year training program

for Tibetan students. After completing their three year course, most artists

then join their workshops, where they must complete an additional three years

as apprentices before they are considered fully qualified artists.

To

make a thangka, first a piece of canvas is stitched onto a wooden frame. It

is prepared with a mixture of chalk, gesso, and base pigment, and rubbed

smooth with a glass until the texture of the cloth is no longer

apparent.

The

outline of the deity is sketched in pencil onto the canvas using

iconograpic grids, and then outlined in black ink. Powders composed of crushed

mineral and vegetable pigments are mixed with water and adhesive to create

paint. Some of the elements used are quite precious, such as lapis lazuli for

dark blue. Landscape elements are blocked in and shading is applied using both

wet and dry brush techniques. Finally, a pure gold paint is added, and the

thangka is framed in a precious brocade boarder.

A

standard thangka painting in Norbulingka, which is about 18 x 12 inches,

takes an artist about six weeks to complete.

These days, it is becoming more and more rare to find genuine thangkas because

of the length of time it takes to learn the skill and create a painting

properly. However, Norbulingka is committed to preserving the skill of thangka

painting in the traditional form.

Some

more institutes in India which offer courses are -

1. Thangde

Gatsal Art Studio and School, Dharamshala, Himachal Pradesh.

2. Institute

of Tibetan Thangka Art Dharamshala, Himachal Pradesh.

3. Living

Buddhist Art & Thangka Painting Center Dharamshala, Himachal Pradesh.

4. Buddha

Thangka Art Gallery, Rishikesh, Uttarakhand.

Spiritual Connection

Aside

from being an aid to spiritual practice, commissioning a thangka is considered

a means of generating spiritual merit, and many times, if an individual is

facing some kind of hardship, a lama is consulted and recommends the creation

of a thangka of a specific deity as a remedy. The artist then designs a thangka

by referring to the measurements of deities detailed in the scriptures,

following the prescription of the lama.

Creating

these one-of-a-kind thangkas requires extensive research, especially as the

descriptions explaining the proportions of each deity are not compiled in one

text, but are located in different volumes throughout the hundreds of volumes

of Buddhist scripture. Furthermore, some texts cannot even be touched unless

one has received the proper initiation for that specific deity.

Because

the art is explicitly traditional, all symbols and allusions must be in

accordance with strict guidelines laid out in the Buddhist scripture. The

artist must be properly trained and have sufficient religious understanding,

knowledge, and background to create an accurate painting.

Conservation

The conservation treatment of a thangka is a complex process that reflects the

complexity of the original composite object. All of the issues raised above

must be evaluated in deciding on the appropriate treatment for a specific

thangka.

For example, a Conservator must look carefully for any exposed colour notations

and not confuse them with iconographic lettering on the final paint layers. A

Conservator must evaluate what regional and stylistic techniques were used in

producing the painting and mounting and also look for damage from past

handling. And finally, the Conservator must examine the current mounting to

determine its relation to the painting and document whether it covers

significant sections of the painting.

Conclusion

Thangkas

are complicated composite objects which are designed to communicate

iconographic ideas in a beautiful and practical form. A thangka in laboratory

or collection may be the production of many painters and tailors with differing

intents, and differing skills and training. The textile mounting may have a

completely different style, date and region of origin from those of the

painting.

Pure,

single artistic intent is lost through a combination of iconographic

specifications, regional and doctrinal differences in style, changes in form

subsequent to the original creation and many years of harsh treatment.

Author is a Mumbai based artist.

The

purpose of this compilation is to document and promote. We have given credits

and reference links in this compilation. In case some are missed, it is not

with malafide intent.

To read all

articles by author