- The essay compares Samkhya and Buddhist thought by stating the Samkhya position in brief, then the Buddhist criticism of Samkhya and the Advaita Vedantin response and compares other parameters for e.g. concept of God and Self, meditation etc.

Sāṃkhya

and Buddhism are amongst two of the oldest philosophical systems from India. At

first glance, they may seem different, but a closer look shows that Buddhism

developed from ideas already present in Sāṃkhya.

Both

traditions aim to answer the same basic question: how can human beings overcome

suffering? They offer different answers, but they share many core ideas,

especially in their early forms.

In fact, Buddhism is not entirely sui generis. It is not a system created from nothing. Instead, it is best understood as an offshoot of Sāṃkhya: a system that keeps the practical and philosophical insights of Sāṃkhya but moves beyond them in subtle and radical ways. In a certain sense, Buddhism is a critique of Sāṃkhya ideas which are always not tenable under scrutiny.

We

will do well to see what the Buddha has to say first and then see how Sāṃkhya

and Advaita Vedantins countered these Buddhist axioms:

An

example that directly undermines the Sāṃkhya concept of an eternal, unchanging

Self (Puruṣa) comes from one of the most important primary scriptures in

the Pali Canon: the Anattalakkhaṇa Sutta.

Reiterating the Sāṃkhya Position in

brief:

Before the critique, it's essential to understand the Sāṃkhya position being critiqued. Sāṃkhya philosophy is a radical dualism positing two eternal, fundamental realities:

Puruṣa (पुरुष): The Self, which is pure consciousness. It

is manifold (many individual puruṣas exist), eternal, unchanging, and a passive "witness" to the world. It does not act.

Prakṛti (प्रकृति): Primordial

matter/nature. It is singular, active, and composed of three constituent

qualities (guṇas). All physical and mental phenomena, including the

intellect (buddhi), ego (ahaṃkāra), and mind (manas), are

evolutes of Prakṛti.

Liberation

(kaivalya) in Sāṃkhya is achieved

through discriminative knowledge (viveka jñāna), where the Puruṣa

realizes its complete separation from Prakṛti and all its activities. The Buddhist on the other hand argues that no such

permanent, independent, and unchanging Self (Puruṣa or ātman) can

be found within experience. The Anattalakkhaṇa Sutta ("The Discourse on the Not-Self Characteristic") demonstrates this by systematically deconstructing the individual into five components (the five aggregates or skandhas) and showing that none of them can be the Self.

This directly refutes the practical tenability of identifying or locating a Puruṣa.

The Analysis of the Five Aggregates

Scripture: Anattalakkhaṇa

Sutta (Saṃyutta Nikāya 22.59 (SN 22.59))

In

this discourse, the Buddha addresses his first five disciples. He breaks down

the entirety of personal experience into five aggregates (pañcakkhandhā):

1.

Form/Matter (rūpa)

2.

Feeling (vedanā)

3.

Perception (saññā)

4.

Mental Formations/Volitions (saṅkhārā)

5.

Consciousness (viññāṇa).

The

Buddha then applies a devastatingly simple and practical line of reasoning to

each aggregate. Here is the structure of his argument, which he repeats for all

five:

He

asks the monks concerning Form (rūpa):

“Bhikkhus, is form permanent or impermanent?" "Impermanent, venerable sir.” “Is that which is impermanent suffering or happiness?” “Suffering, venerable sir.” “Is it fitting to regard what is impermanent, suffering, and subject to change as: 'This is mine, this I am, this is my self'?” "No, venerable sir."

He

repeats this exact sequence for feeling, perception, mental formations, and

finally, for consciousness (viññāṇa)—the very aggregate that Sāṃkhya would associate with the Puruṣa.

Why This Is a Critique of Sāṃkhya's Practicality

1. It Dismantles the "Witness": The Sāṃkhya Puruṣa is pure, unchanging consciousness. However, the Buddha's analysis in the Sutta demonstrates that consciousness (viññāṇa) as we experience it is not a

monolithic, unchanging entity. It arises dependent on conditions (e.g.,

eye-consciousness arises from the eye and a visible form), it is impermanent (anicca),

and it is unsatisfactory (dukkha). Therefore, the very candidate for the

Self is shown to be conditioned and unstable, making it untenable as an

eternal, passive witness.

2. It Challenges the Locus of Control: The Buddha adds

another layer to his argument. If any of these aggregates were a true Self, it

should be fully controllable. He states:

“If, bhikkhus form were the self, this form would not lead to affliction, and it would be possible to have it of form: ‘Let my form be thus; let my form not be thus.' But because form is not-self, it leads to affliction, and it is not possible to have it of form: 'Let my form be thus; let my form not be thus.’”

This is a practical, empirical test. We cannot command our bodies to not get sick or old. We cannot command our feelings to always be pleasant. We cannot command our consciousness to remain stable. Since there is no ultimate control, none of these can be the “Self.” This directly undermines the idea of a sovereign Puruṣa

that is distinct from and yet somehow associated with the psycho-physical

organism.

3. It Shows the Sāṃkhya View Leads to Suffering: The Sutta's conclusion is that identifying with any of these impermanent, conditioned phenomena as "Self" is the very root of clinging and suffering. The Sāṃkhya project, from a Buddhist viewpoint, is an attempt to grasp at a metaphysical entity (Puruṣa) which is simply a refined

concept of the Self. By positing its existence, one creates a subtle object of

attachment. The Buddhist path, in contrast,

finds liberation by seeing through the illusion of any self, thereby

ceasing all clinging.

In

summary, the Anattalakkhaṇa Sutta (SN 22.59) provides a foundational and

practical refutation of the Sāṃkhya view by inviting the practitioner to look

at their own experience. It concludes that no permanent, independent Self (Puruṣa) can be located, and the very belief in one is a philosophical error that is “not tenable in practice” for anyone seeking liberation from suffering.

Now

against this apparently watertight Buddhist logic, we now see how it is

impossible that the Buddhist is right. The Buddhist argument, particularly as

articulated in the Anattalakkhaṇa Sutta, was met with powerful and sophisticated counter-critiques from Hindu philosophical schools, chiefly Sāṃkhya and Advaita Vedānta. They essentially argue that the Buddha's analysis is either incomplete (Sāṃkhya) or fundamentally misguided in its method (Advaita Vedānta). They contend that the Buddha correctly identified that the phenomenal aggregates are not the Self, but then made the erroneous leap to conclude there is no Self at all.

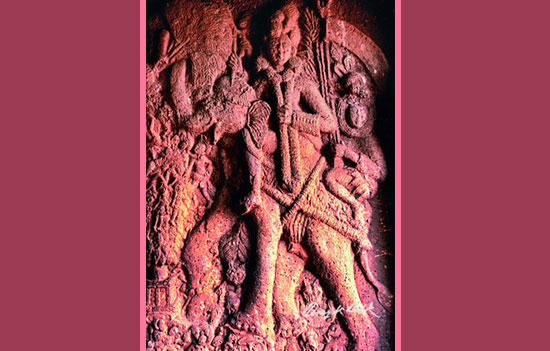

Earliest depiction of Lord Indra in Bhaja Cave,

Maharashtra. Pic Benoy K Behl.

Earliest depiction of Lord Indra in Bhaja Cave,

Maharashtra. Pic Benoy K Behl.

The Sāṃkhya Critique: An Incomplete

Analysis

The Sāṃkhya school would agree with the Buddha's entire analysis of the five aggregates: form, feeling, perception, volitions, and phenomenal consciousness are indeed all products of Prakṛti (primordial nature), and are therefore impermanent, mutable, and "not-self."

However,

Sāṃkhya argues that the Buddha stopped his analysis too soon. After

deconstructing everything that belongs to Prakṛti, he failed to infer

the existence of the entity for which all of this machinery exists: the pure,

unchanging consciousness, Puruṣa. The Sāṃkhya argument is not that the

Self is found within the aggregates, but that its existence must be

inferred because of the aggregates.

The foundational text of classical Sāṃkhya, Īśvarakṛṣṇa's Sāṃkhyakārikā,

provides a famous verse that lists the arguments for why Puruṣa must

exist.

संघातपरार्थत्वात् त्रिगुणादिविपर्ययादधिष्ठानात् । पुरुषोऽस्ति भोक्तृभावात् कैवल्यार्थं प्रवृत्तेश्च ॥ Sāṃkhyakārikā

Verse 17

Transliteration: saṅghāṭa-parārthatvāt

triguṇādi-viparyayād-adhiṣṭhānāt | puruṣo'sti bhoktṛ-bhāvāt kaivalyārthaṃ pravṛtteś-ca || 17 ||

Translation: “The Self (Puruṣa)

must exist because:

1.

Aggregates must exist for the sake of another (saṅghāṭa-parārthatvāt).

2. This 'other' must be the reverse of that which is composed of the three guṇas

(triguṇādi-viparyayāt).

3.

There must be a basis of superintendence or control (adhiṣṭhānāt).

4.

There must be an enjoyer or experiencer (bhoktṛ-bhāvāt).

5.

And there is striving for the sake of liberation (kaivalyārthaṃ pravṛtteś-ca).”

This

verse directly confronts the conclusion of the Anattalakkhaṇa Sutta.

Point 1 & 4 (Aggregates for Another/Enjoyer): The Buddha shows that the five aggregates are a selfless process. Sāṃkhya retorts: a process or a collection of things (like a bed or a chariot, or the five aggregates) cannot exist for its own sake. It must exist for an external user or "enjoyer." The body-mind complex is an instrument, and an instrument implies an agent or experiencer who uses it. This experiencer is the Puruṣa.

Point 2

(Reverse of the Guṇas): The Buddha proves the aggregates are impermanent and

cause suffering. Sāṃkhya agrees and says this is the nature of Prakṛti

and its three guṇas. Therefore, the Self for which they exist must have

the opposite qualities: it must be eternal, pure, and beyond the guṇas.

Point 5

(Striving for Liberation): Why would a selfless process seek liberation? The

very striving for an end to suffering implies there is someone who

suffers and who can be liberated. This someone is the Puruṣa.

In essence, Sāṃkhya argues that the Buddha's "not-self" conclusion is like examining every part of a chariot, finding no charioteer in the wood or wheels, and declaring the charioteer doesn't exist. Sāṃkhya insists the charioteer (Puruṣa) is logically necessary to explain the chariot's existence and purpose.

The

Advaita critique is even more profound. Advaita Vedānta, championed by Śaṅkara, argues that the Buddha's method of searching for the Self is fundamentally flawed. The Buddha tries to find the Self (Ātman) as an object among other objects (form, feeling,

etc.). The core teaching of Advaita is that the Self is the eternal Subject and

can never be objectified.

To

look for the Self is a category error. It is like trying to see your own eye

with your eye, or trying to illuminate the sun with a torch. The Self (Ātman)

is the very light of Consciousness (Cit) that illuminates the five

aggregates.

Murti of Buddha replaced Vishnu in the sanctum at Angkor Wat Temple, Cambodia.

Murti of Buddha replaced Vishnu in the sanctum at Angkor Wat Temple, Cambodia.

The Seer Who Cannot Be Seen

This principle is articulated masterfully in one of the oldest and most important Upaniṣads, and it forms the bedrock of Śaṅkara's refutation.

In this passage, the sage Yājñavalkya is questioned by Uṣasta Cākrāyaṇa, who asks him to explain "the Brahman that is immediate and direct—the Self that is within all." Yājñavalkya responds:

न दृष्टेर्द्रष्टारं पश्येः, न श्रुतेः श्रोतारं शृणुयाः, न मतेर्मन्तारं मन्वीथाः, न विज्ञातेर्विज्ञातारं विजानीयाः । एष त आत्मा सर्वान्तरः । Bṛhadāraṇyaka

Upaniṣad

3.4.2

Transliteration: na dṛṣṭer-draṣṭāraṃ paśyeḥ, na śruteḥ śrotāraṃ śṛṇuyāḥ, na mater-mantāraṃ manvīthāḥ, na vijñāter-vijñātāraṃ vijānīyāḥ. eṣa ta ātmā sarvāntaraḥ.

Translation: “You cannot see the Seer of seeing. You cannot hear the Hearer of hearing. You cannot think the Thinker of thinking. You cannot know the Knower of knowing. This is your Self that is within all.”

How This Negates the Buddhist View:

This

statement completely invalidates the Buddhist methodology from the Advaita

perspective.

1. The Self is Not an Object: The Anattalakkhaṇa Sutta proceeds by objectifying each aggregate for inspection ("Bhikkhus, what do you think of form?"). Yājñavalkya's teaching states that the true Self—the Seer, the Knower—is the one doing the inspecting. It is the transcendental subject and can never be made into an object of perception or cognition. The moment you "know" something, that something is an object, and the Self is the knower behind it.

2. The Self is Self-Evident: For Advaita, the Self (Ātman) requires no

proof because it is the foundation of all proof. To deny the Self is to deny

the very denier. Śaṅkara, in his commentary on the Brahma Sūtras (especially in

his introduction, the Adhyāsa Bhāṣya), argues that the "I"-consciousness (asmat-pratyaya) is the undeniable substrate

of all experience. While we can doubt everything else, we cannot doubt the

existence of the one who doubts.

3. Buddhism Mistook the Reflection for Reality: The "consciousness" (viññāṇa)

that the Buddha analyzes as the fifth aggregate is, for an Advaitin, merely

phenomenal, reflected consciousness. It is the light of the true Self (Ātman)

illuminating the mind (antaḥkaraṇa). The Buddha correctly saw that this reflection was impermanent, but he failed to recognize the original, unchanging source of the light—the eternal Consciousness itself (Brahman/Ātman).

Therefore, from the Advaita standpoint, the Buddha's discovery of "not-self" in the aggregates is not a discovery of ultimate truth, but a predictable failure resulting from a flawed search. He looked for the Self where it could never be found—in the realm of objects—and thus concluded it didn't exist, falling into what Advaitins would consider a sophisticated form of nihilism (śūnyavāda).

It

is keeping in mind the errors of Buddhist metaphysics we return to our survey

of Sāṃkhya and Buddhism.

Yama, or Emma, Inoji, Kyoto, Japan. Photograph by Benoy K Behl

Yama, or Emma, Inoji, Kyoto, Japan. Photograph by Benoy K Behl

Shared Beginnings

Before

the Buddha reached enlightenment, he studied with two meditation teachers.

One of them, Alara Kalama, taught practices that closely followed early Sāṃkhya thinking. He trained the Buddha in deep states of meditation, including what is called the “sphere of nothingness.” These meditative states are also described in Sāṃkhya-Yoga philosophy.

The

very name of the Buddha’s birthplace—Kapilavastu—points to a connection with Sāṃkhya. It is believed to be named after Sage Kapila, who founded the Sāṃkhya school. Some legends even suggest that the Buddha was Kapila in a previous birth. Whether or not these stories are taken literally, they show that the intellectual and spiritual environment in which the Buddha grew up was already shaped by Sāṃkhya ideas.

The Shared Problem: Suffering

Both

Sāṃkhya and Buddhism begin by trying to solve the problem of human suffering. Sāṃkhya

says there are three types of suffering:

Ādhyātmika,

Ādhibhautika, and Ādhidaivika duḥkha

(Suffering

caused by oneself, by others, and by unseen forces)

The

Sāṅkhyakārikā (Karika 1) says:

दुःखत्रयाभिघाताज्जिज्ञासा तदभिघातके हेतौ ।

duḥkhatrayābhighātāj jijñāsā tadabhighātake hetau

“Suffering from the three sources leads to inquiry into its cause and removal.”

Buddhism,

too, begins with the recognition of suffering (dukkha) as the first Noble

Truth. Neither system believes that prayers, sacrifices, or rituals can remove

suffering. Instead, both focus on direct knowledge, inner work, and personal

transformation.

Kapila Rishi, founder of Samkhya philosophy. Said to have meditated in Amarkantak, Madhya Pradesh, where the Holy Narmada starts.

Kapila Rishi, founder of Samkhya philosophy. Said to have meditated in Amarkantak, Madhya Pradesh, where the Holy Narmada starts.

No Creator God as understood by

contemporary religions

Both

traditions reject the idea of a creator god. Sāṃkhya says the world arises from

the interaction between Purusha (pure consciousness) and Prakṛti (material

nature), without any divine being behind it. This is stated in the Sāṅkhyakārikā

(Karika 57):

कर्मणो नाधिकारः पुरुषस्यास्त्यकर्तृत्वात् ।

karmaṇo

nādhikāraḥ puruṣasyāstyakartṛtvat

“Purusha is not the doer of actions; hence, he cannot be the cause of creation.”

Buddhism also teaches that the world runs on causes and conditions, not the will of a god. It teaches paṭiccasamuppāda—dependent origination—as the explanation for all things. Both systems are early forms of rational and atheistic thought in India. Read Concept

of God in Sanatana Dharma and Christianity

Lord Indra temple at Sukumwit street, Bangkok.

Lord Indra temple at Sukumwit street, Bangkok.

Meditation and Understanding the Mind

The Buddha’s training in meditation included deep states known in Buddhism as the four arūpa-jhānas (formless absorptions), which align closely with meditative practices known in Sāṃkhya-Yoga systems. These stages are:

Ākāsānañcāyatana – Infinite space (ākāśānantyāyatana)

Viññāṇañcāyatana – Infinite consciousness (vijñānānantyāyatana)

Ākiñcaññāyatana – Nothingness (ākiñcaññāyatana)

Nevasaññānāsaññāyatana – Neither perception nor non-perception (naiva-saṃjñā-nāsaṃjñāyatana)

These

are recorded in Majjhima Nikāya 26 (Ariyapariyesanā Sutta) and Majjhima

Nikāya 121 (Cūḷasuññata Sutta).

Sāṃkhya

likewise emphasizes deep meditation and internal detachment. The Yogabhāṣya,

associated with Sāṃkhya, affirms:

योगश्चित्तवृत्तिनिरोधः ।

yogaś

citta-vṛtti-nirodhaḥ

“Yoga is the stopping of the movements of the mind.”

This

shared structure of meditative insight makes it clear that Buddhism adopted—not invented—these inner methods. It refined and

reinterpreted them.

The Self: Divergence from Sāṃkhya

The

key difference between the two systems lies in how they understand the self. Sāṃkhya

teaches that every person is at their core a pure, unchanging self, called

Purusha. Liberation comes when one realizes that they are not the body or the

mind, but only this silent witness:

सत्त्वपुरुषान्यताख्यातिर्अविवेकः ।

sattva-puruṣānyatā-khyātir

avivekaḥ

“Not knowing the difference between nature and the self is ignorance.”

(Sāṅkhyakārikā,

Karika 64)

In contrast, Buddhism teaches anatman—there is no permanent self. The Buddha said that none of the five aggregates (form, feeling, perception, mental formation, and consciousness) should be taken as a self. As he declared:

"Sabbe dhammā anattā."

“All things are not-self.”

(Anattalakkhaṇa

Sutta)

But even here, Buddhism does not fully break with Sāṃkhya. Some scholars argue that the Buddha was not rejecting the experience of pure consciousness, but only the idea of it as a fixed, separate self. His method of not-self (anatta) mirrors Sāṃkhya’s method of viveka (discrimination) by removing false identifications.

MAITREYA enroute from Leh to Kargil in Ladakh. Carved about 1st century a.d.

MAITREYA enroute from Leh to Kargil in Ladakh. Carved about 1st century a.d.

The Practice: Knowing and Letting Go

Both systems teach that knowledge—not belief—frees the mind. Sāṃkhya calls this viveka-khyāti, the clarity that we are not the body or mind. Buddhism uses mindfulness and insight to see that all things are impermanent, unsatisfying, and not-self.

Sāṃkhya aims for kaivalya—complete separation of Purusha from Prakṛti. Buddhism aims for nirvana—freedom from craving, ignorance, and rebirth. The process is different, but the direction is the same.

They

also share ethics: a middle way between indulgence and self-denial. Both accept

karma and rebirth. Sāṃkhya says karmic impressions continue through the subtle

body; Buddhism says a stream of causes and consciousness continues, though

without a fixed soul.

Buddhism Is Not Sui Generis

Buddhism is not a system created in a vacuum. It did not arise without influence or precedent. It grew out of a living tradition of Indian philosophy—especially Sāṃkhya. The Buddha inherited its language, its tools, and its methods. What he did was refine them. He kept Sāṃkhya’s rejection of divine control, its analysis of suffering, and its internal disciplines. But he took a bold turn by questioning even the belief in an eternal witness.

Conclusion

Buddhism did not appear out of nowhere. It emerged from an Indian intellectual world where Sāṃkhya was already asking the deepest questions about life and mind. The Buddha’s teachers were part of this tradition. His methods—especially meditation and inner analysis—were already part of Sāṃkhya’s heritage.

But the Buddha went further. Sāṃkhya says, “Know you are Purusha.” Buddhism says, “See that all clinging—even to Purusha—is suffering.”

Buddhism is both a child of Sāṃkhya and its strongest critic. It keeps the tools, keeps the goal, but redefines what it means to be free. In doing so, it proves that new truths often grow from old roots—not in rejection, but in fearless transformation.

Author Dr S Chattopadhyay Ph. D is a student of Comparative Religions.

Also read

1.

What

is common to the Bhagavad Gita and Dhammapada

2.

Lord

Indra in Buddhism

3.

Common

Hindu Buddhist strains in Thailand, Japan and Cambodia

4.

Introduction

to Buddhism

5.

Concept

of Atheism in Samkhya and Buddhist Philosophy

6.

Commentary

on BRIHADARANYAKA UPANISHAD

To

read all articles by author