- Credit for success of ISRO goes to its

Team, Dr Mahendra Sarkar and Indian Institute of Science. Swami Vivekananda,

Jamshedji Tata, Sister Nivedita, Maharaja of Mysore helped set up IISc. How IISc

contributed to ISRO?

Yesterday evening the Chandrayan 3 Lander

made a successful landing on the south pole of the moon. The national mood was

similar when India won the cricket World Cup in 1983. Pranams ISRO.

Congress leader Jairam Ramesh was quick

to tweet, as if to say that the foundation for this success was laid during Congress rule. “In February 1962, the farsightedness of Homi Bhabha and Vikram Sarabhai created INCOSPAR (Indian National Committee for Space Research). In August 1969, the development-oriented Vikram Sarabhai established ISRO. Between 1972 and 1984, Satish Dhawan provided extraordinary scientific, technological and managerial leadership to decisively shape the ISRO that we know today. Along with him, we remember Brahm Prakash, the great metallurgist who made fundamental contributions to both our nuclear and space programmes.”

The tweet does not mention of Congress contribution between 1985-1989, 1991-1995 and 2004-10.

Actually

the foundation for the Indian Institute of Science (IISc), the cradle for ISRO,

was laid in the 19th century.

This essay covers contribution of Dr Mahendra Sarkar; India’s first modern science visionary. Plus Swami Vivekananda, Jamshedji Tata, Sister Nivedita and Maharaja of Mysore’s role in setting up IISc. Know how IISc

contributed to ISRO, its Budget and number of Women employed. Lastly, about HAL

that was founded by Walchand Hirachand.

Together these institutions helped

create an ecosystem for aeronautics in Bengalaru. As India begins to

manufacture electronic goods, it is realizing the importance of an ecosystem. Read

about contributors. This ecosystem needs protection from anti-India forces.

1. Dr Mahendra Lal Sarkar 1833-1904

Dr Sarkar was the second MD graduate

from Calcutta Medical College. Although educated as in allopath he took to

homeopathy and treated notably, Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay and Sri Ramakrishna.

As a devotee, Dr Sarkar spent a lot of time with Sri Ramakrishna and is said to

be influenced by him.

Dr Sarkar realized the need for a forum

to exchange scientific knowledge in India. After all, the country had a rich

tradition in science.

Read The Indian

Foundations of Modern Science

“Since 1867 he started a campaign for a National Science Association as he felt India needed its own scientific knowhow away from the British supremacy and thus planned for an association that would be funded, run, and managed by native Indians, with the aim of turning out a pool of scientists for national reconstruction.

Thus, was born the Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science in 1876 and Sarkar was its first secretary. It had basic science departments such as Physics, Chemistry, Mathematics, Physiology, Geology, Botany, etc. and notable Indian scientists participated in the association. Regular lectures and demonstrations were arranged for the public to popularize science.” Reference and

credits

The institution founded by Dr Sarkar

provided a platform to C V Raman to carry out research. Read on.

Even though Nobel laureate C V Raman joined the Indian Finance department in 1907 “Raman found opportunities for carrying on experimental research in the laboratory of the Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science at Calcutta (of which he became Honorary Secretary in 1919). After 15 years at Calcutta he became Professor at the Indian Institute of Science at Bangalore (1933-1948).” Source

2. Why Calcutta

Bengal was the first region to be captured by the British due to their victory in the (1757) Battle of Plassey. Calcutta became the capital of British India in 1772. The Supreme Court was established here in 1774. Reference It was but natural that European medicine medical colleges and educational institutions were set up in the city. Note that West Bengal’s two living Nobel Laureates live outside India.

IISc Bengaluru.

IISc Bengaluru.

The story of modern Indian science

started on a ship. Read on.

3. Contribution of Swami

Vivekananda, Jamshedji Tata, Sister Nivedita to setting up of Indian Institute

of Science

In 1893 Swami Vivekananda (monk) and J N Tata (trader-industrialist) were together on a ship from Yokohama in Japan to Vancouver in Canada. This is before Swamiji’s address at the Parliament of Religions in September 1893.

Swamiji urged J N Tata to get into manufacturing instead of trading (a bit like today’s Make in India). This would create more jobs and development. “He also talked of training Indians not just in science, but also technology, so that the country’s requirements could be significantly fulfilled by its domestic manufacturing.” Source and

Reference

“Impressed by Vivekananda’s views on science and deep-rooted patriotism, Jamshedji requested his guidance in his campaign in establishing a research Institute in India. The visionary monk smiled, gave his blessings and remarked, “How wonderful it would be if we could combine the scientific and technological achievements of the West with the asceticism and humanism of India!” Source

Extract from J N Tata’s 1898 letter to Swamiji from the Tata.com site.

“I recall these ideas in connection with my scheme of Research Institute of Science for India, of which you have doubtless heard or read. It seems to me that no better use can be made of the ascetic spirit than the establishment of monasteries or residential halls for men dominated by this spirit, where they should live with ordinary decency and devote their lives to the cultivation of sciences –natural and humanistic.”

Mr Tata wanted Swamiji to head the institute of science and give a lease of life to India’s ancient traditions.

Vinay Logani wrote in the

wire.in, “Tata, was referring in the letter to his pledge of a gift of 200,000 in pound sterling (about Rs 30 lakh then), widely reported nationally towards setting up a research institute to “induce the students of this country to undertake researches on the problems of tropical diseases or tropical chemistry, to investigate the vast and neglected materials of our national history and Indian philology” and “to found laboratories and libraries, where students may work under the direction of great teachers.”

Swamiji refused the offer due to his ongoing efforts in setting up of the Ramakrishna Mission but sent Sister Nivedita to meet Mr Tata.

Sister Nivedita.

Sister Nivedita.

Thereafter, “Sister Nivedita, began to actively campaign for the actualisation of this scheme by this great patriot-industrialist and wrote several articles in the English press championing it.” The Scottish Irish lady, born Margaret Elizabeth Noble’s life changed after she met Swamiji in 1895. She came to India in 1898. Swamiji gave her the name Nivedita.

Read Sister Nivedita – Offering of grace and Sister Nivedita – Vajra Shakti

In 1901, Nivedita took up the matter with the education department in London. Vinay wrote, “Sir Birwood reiterated the establishment’s prejudice with regard to the Tata scheme as, in his opinion, even the three universities in the presidency towns had failed to produce an original mind since 1857.” Not one to lose heart Nivedita wrote to world thinkers.

Swamiji passed away in 1902 and Mr Tata

in 1904. The proposal was finally approved by Lord Minto in 1909. Source and

Reference

The rulers of Mysore State shared Tata’s commitment to education and research. The Maharaja’s father, H.H. Chamaraja Wadiyar, was a devoted disciple of Swamiji.

The “Regent Queen Maharani Kempananjammani Vani Vilasa Sannidhana-her son Krishnaraja Wadiyar was a minor then, provided 371 acres and 16 guntas of land in Bangalore, funds for capital expenditure, and an annual contribution for Tata’s ambitious project. The remaining money to set up IISc came from the colonial government of India.” Source

The contributions of Swami

Vivekananda, the Maharaja of Mysore and importantly, Sister Nivedita to the

establishment of IISc need to be more widely known.

She also helped J C Bose. “From organising financial support to editing his manuscripts, Sister Nivedita made sure the pioneering Indian scientist was able to continue with and share his work.” In one of his letters Bose wrote, “Sister Nivedita was also greatly interested in the revival of all intellectual advances made by India, and it was her strong belief in the advance of Modern Science accomplished by Indian Men of Science that led me to found my Research Institute.” Source and read Sister

Nivedita made sure J C Bose never gave up

Swami Sandarshanananda wrote. “Nivedita wanted these two great sons of India to come close in order to make the country strong.” Source Her

efforts made them meet and appreciate each other.

4. Birth of Indian Institute of Science in 1909 (IISc)

Thus, ‘The Tata Institute of Science’ was born. It was renamed Indian Institute of Science (IISC) in 1911.

“The Institute also grew to include departments such as those of Biochemistry and Physics. The latter was set up under Sir CV Raman, a Nobel Laureate who also became the first Indian Director of IISc in 1933. IISc counts among its former students and faculty several eminent scientists such as Homi J Bhabha, the founder of India’s nuclear program, Vikram Sarabhai, the founder of India’s space program, the meteorologist Anna Mani, the biochemist and nutrition expert Kamala Sohonie, and solid state and materials scientist CNR Rao, to name just a few.” Source Satish Dhawan was Director IISc from 1963 to 1981.

5. How IISc contributed to

ISRO?

In 2019 Deepika S wrote How IISc

Launched Aerospace Research in India on the IISc site. Excerpts:

“From HAL to ISRO, IISc's enormously talented scientists played pivotal roles in building India’s aerospace programme.

IISc set up its Department of Aeronautical Engineering in 1942 – bang in the middle of World War II. Although the war wasn’t the stated focus of the Department of Aeronautical Engineering, it was involved in it straight away. Classes began formally in the Department on 1 January 1943 with a compact one-year course populated with 15 engineering graduates and just two members of faculty: a lecturer and an assistant professor. That assistant professor was Vishnu Madhav Ghatage.

HAL went from overhauling and repairing British and American aeroplanes during the war to making indigenous aircraft, and its close relationship with IISc is one that continues to this day.”

Because IISc and HAL were already in

Bangalore (now Bengaluru) the National Aeronautical Laboratory (NAL) relocated

from Delhi in 1960.

“The year NAL moved to Bangalore, IISc’s Aerospace Department began helping them design and set up a large transonic/supersonic wind tunnel, which could be used to test models of vehicles that could travel close to or faster than the speed of sound. P Nilakantan was NAL’s Director from its inception to his untimely death in 1964. He was an IISc alumnus who studied under CV Raman.”

IISc was at the centre of the aeronautical ecosystem that was being created in Bangalore.

“The criss-crossing trajectories of the Aerospace Department’s faculty and alumni have helped build what its current Chairperson, S Gopalakrishnan, describes as an “ecosystem”. From training programs for DRDO scientists to providing IITs with faculty members, Gopalakrishnan says the Department’s footprint has been ubiquitous. HAL, NAL, and ISRO are its close relatives.

However, considering the comparatively large role that ISRO plays in the public imagination and the strong connection it would come to have to the Aerospace Department, it is perhaps ironic that the Department had little to with ISRO’s earliest years. There, the seed appears to be World War II: without it, there may never have been a direct link at all.”

It was at IISc that Sarabhai met Homi J Bhabha, whom author Amrita Shah describes as “the man who was to found India’s atomic energy programme and loom like a Colossus over Indian science until his death in the mid-1960s.”

Would they have met if there was no IISc is difficult to answer?

This India Today report explains the sequence of events well. “Bhabha was keen on developing nuclear weapons for the country's defence. At his Cosmic Ray Research Unit at IISc, Bhabha began to work on the theory of point particles movement, while independently conducting research on nuclear weapons in 1944. Bhabha realised that being a young nation, India needed to be independent when it came to energy, and looked at nuclear power towards that end.

Funded by industrialist JRD Tata, Bhabha started the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR) in 1945, which later went on to play a major role in India's space program.”

TIFR began functioning within the Cosmic Ray Research Unit on the campus of IISc, Bangalore and moved to Bombay (now Mumbai) in October that year.

In 1954, the government created the Department of Atomic Energy (DAE). Subsequently, in 1958, the Atomic Energy Commission came under the Department of Atomic Energy. Seeing the launch of Sputnik satellites by the Soviet Union, Sarabhai convinced the government of the importance of a space programme. In August 1961, the Department of Atomic Energy (DAE), whose secretary was Bhabha, was asked to look after space research. In 1962, Bhabha founded the Indian National Committee for Space Research (INCOSPAR) as a wing under the Department of Atomic Energy.”

According to the Tata.com site, “IISc has helped create and nurture other laboratories and scientific institutions within the country. The Tata Institute of Fundamental Research and the Atomic Energy Commission were born here. In fact, Homi Bhabha wrote the proposals for creating both these institutions when he was part of the faculty of the Institute. The Indian space programme, too, was developed here.”

Deepika also wrote, “In 1962, Sarabhai was appointed Chairman of the Indian National Committee for Space Research (INCOSPAR) and began looking for a suitable location for their sounding rocket experiments: they settled on Thumba, a fishing village in Kerala. In November 1963, the first sounding rocket was launched from India. Six years later, INCOSPAR grew into ISRO.

When Sarabhai passed away in 1971, Dhawan, IISc’s Director at the time, was contacted by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, and asked to run ISRO.” One of the two conditions by Dhawan was that ISRO be shifted to Bangalore.

“Dhawan also brought IISc’s Aerospace Department directly into the picture. Aravamudan writes that he was “very particular that local industry and academia should be associated with the programmes. He felt there should be a two-way dissemination and absorption of expertise. So he inducted organisations like HAL, HMT and BEL and institutions like IISc and government research laboratories to partner ISRO.”

What we call public-private partnership today. This is certainly not easy to achieve even today. In the 1970’s this must have been a real and huge challenge.

“K Kasturirangan, ISRO’s former Chairperson, said that Dhawan “transformed every institution he got involved with” and “strengthened and gave new direction to the Indian space program.” And in the process, Dhawan appears to have placed the Aerospace Department in the forefront of Indian space technology.”

Since Deepika S referred to HAL as a

close relative of IISc here is brief information about its formation.

6. Hindustan Aeronautics

Limited

(HAL)

According to the HAL site Hindustan Aircraft Limited was incorporated in 1940 by

Shri Walchand Hirachand (1882-1953) in

association with the then Government of Mysore, with the aim of manufacturing

aircraft in India. The Government of India took over its management in 1942. In 1951, the HT-2 Trainer aircraft, designed and produced by the company under the leadership of Dr. V. M. Ghatge flew for the first time. In 1964, Aeronautics India Limited and Hindustan Aircraft Limited were merged to form HAL.

Note that Walchandnagar Industries are

equipment suppliers to ISRO even today. Their association

started in 1973 with manufacturing of motor cases for SLV-3. Source

7. Budget ISRO

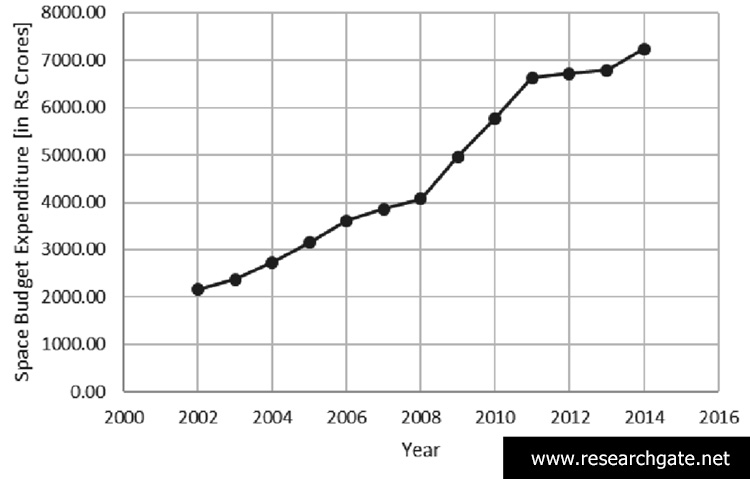

This chart (source-researchgate.net) shows the India’s Space Budget. It moved up from app Rs 2,000 crs in 2002 to over Rs 7,000 crs in 2014.

India’s Space Budget 2002 to 2014.

India’s Space Budget 2002 to 2014.

According to a report in spacereport.org the

allocations were Rs 6,959 crs in 2015-16016, Rs 8,045 crs 2016-07 and Rs 9,156

crs in 2017-18. As per this report in The New Indian Express the budget

allocations were 2019-20 Rs 13,017 crs, 2020-21 Rs 9,500 crs, 2021-22 Rs 12,642

crs, 2022-23 Rs 13,700 crs and 2023-24 Rs 12,544 crores.

Read Tracking ISRO

Budget over the years

Clearly, barring the pandemic year of

2020-21, budgetary allocations for Space are going up. Read How India keeps

its space missions frugal

8. Number of Women

Employees ISRO

As per the Annual Report for 2022-23

ISRO has 16,079 employees of whom 3,199 are women (20%). Of 3,199 scientific

and technical staff are 2,058.

9. What are the benefits

of a successful ISRO?

10. Anti-India

forces might seek to harm Indian organizations that are helping India scale new

heights. They need protection by the Central and State governments. Do

not under-estimate your enemy.

Author is a chartered accountant who is inspired by the Rishis and Yogis of Bharat, Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, Guru Govind Singhji and Indian Women Warriors.

Also

read

1. A

very brief history of Indian Science

2. Understanding

mysticism through quantum physics

3. The

Voice of Life by J C Bose

4. How

Indian Maths defined Zero as a concept

5. Talks

on maths in a metrical form

6. Landmarks

of Science in Early and Classical India

7. Chandrayaan’s success will motivate private space industry enterpenurs