- Read

about life and thoughts of Bhagat Singh and know who his fellow fighters were. Despite

his socialistic leanings, he did not join the ranks of the leftists. Likewise,

his love for humanity did not land him in a religious cradle.

The sapling of freedom is nurtured by the blood of martyrs. Bhagat Singh (1907-1931) sacrificed his life at the altar of India’s freedom without a groan on his lips or a tear in his eyes. He was no ordinary martyr to be remembered only for his chivalrous deeds. Rather, he personified the forces which aimed both at the political and social emancipation of his motherland.

Bhagat

Singh was not a man but a movement, nay, a tornado that swept across the nation

to shake off the complacency of his countrymen, the naive mendicancy of elite

groups and the somewhat mild postures of political leadership.

The

promethean hero of Indian nationalism stole the fire of patriotic ardour from

the sublime depths of human psyche, and spread it all over in the hope that one

day his motherland would rise to its ancient glory and make others bask in the

sunshine of its eternal values so essential for the progress and well-being of

mankind. He promenaded on the shores of death to show that human dignity is

more precious than life itself, that servility is a sin and that any attempt to

break man-oriented shackles leads one nearer to the path of virtue.

Born

on September 27, 1907 at Banga in Jaranwala tehsil now in Pakistan, Bhagat

Singh, the third son of Kishan Singh and his wife,

Vidyavati, hailed from a family of revolutionaries who originally

belonged to Khatkar Kalan, a suburb of Jalandhar district. At a tender age, he

imbibed the best of the prevailing traditions and ideologies in a short while

and came to sense the misery of his countrymen under an alien regime, and the

oppressive social structure.

Different strands of thought –the Arya Samajist, the pyrrhonistic, the humanist and the Marxist–Leninist went into the making of his personality.

First

published in Journal of Bharatiya Vidya Bhawan.

At

home, he assimilated in him the nobility of his mother, Vidyavati, the literary

acumen of his grandfather, Arjan Singh, the zeal for social service of his

father Kishan Singh and the sacrificing spirit of his uncle, Ajit Singh.

As

a student of D. A. V. School, Lahore, in 1916, he came under the spell of some well–known political celebrities such as Lala Lajpat Rai (1865-1928), Sufi Amba Prasad (1858-1919) and Rash Behari Bose (1886- 1945). He acquired the skill of writing while he worked on the staff of Arjan, Kirti and Pratap at different periods of time.

The execution of the young lad, Kartar Singh Sarabha (1896- 1915), the Rowlatt Satyagraha of 1919 characterised by massive demonstrations against the British Raj, the brutal slaughter of civilians at Jallianwala Bagh, Amritsar (1919), the success of the Russian Revolution (1917), the 4th May Movement in China (1919) aimed at annihilating “the dregs of history, the rule of Confucius and the exclusive ranks of the mandarins” and, the rise of working class movements in different parts of India influenced him greatly and strengthened his determination to rid the country of all forms of exploitation–political, social or economic in nature. The deep urge to serve his country often brought Sarabha’s famous couplet on his lips.

Seva desh di jindariye’ bari aukhi Gallan karnian dher sukhalian ne; Jinhan desh seva vich pair paya Unah lakhan musibatan

jhalian ne.

“It is easy to indulge in a gibberish but difficult to serve the country. Those who undertake the task of serving their motherland are sure to suffer many privations.”

Bhagat Singh’s initial revolutionary fervour got ample expression in the Non-cooperation Movement (1920-22) and the Gurudwara Reform Movement launched respectively by Mahatma Gandhi and, the Akali (Sikh) leadership. The formation of Naujawan Bharat Sabha in Lahore (1925), of which he became the General Secretary and that of Hindustan Socialist Republican Association in Delhi, three years later, which he organised along with Shiv Varma, Sukh Dev, Bejoy Kumar Sinha and Ajoy Ghosh, set his work on systematic lines.

Ajoy Ghosh (1909-1962) a revolutionary from Uttar Pradesh, later wrote that the anti-imperialist struggle was to be so waged as to culminate in the formation of a socialist state. Armed action by individuals and groups was deemed necessary for achieving the set goal. “Nothing else, we held, could smash constitutionalist illusions, nothing else could free the country from the grip in which fear held it. When the stagnant calm was broken by a series of hammer blows delivered by us at selected points and on suitable occasions against the most hated officials of the Government and a mass movement was unleashed, we would link ourselves with that movement,... and give it a socialist direction.”

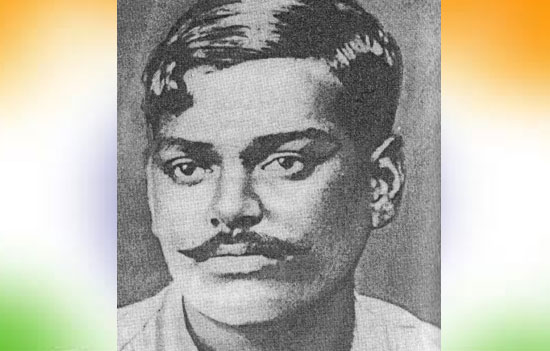

Chandrasekhar Azad, Rajguru, Bhagat Singh avenged death of Lala Lajpat Rai.

Chandrasekhar Azad, Rajguru, Bhagat Singh avenged death of Lala Lajpat Rai.

The

accounts of the role Bhagat Singh played in

boycotting the Simon Commission (1928) and then avenging the death of his

mentor, Lala Lajpat Rai by killing J. P. Saunders, Deputy Superintendent

of Police (in association with Shivaram

Rajguru 1908-1931, and Chandrashekhar

Azad, 1906-31), by throwing two non-lethal bombs and the Hindustan

Socialist Republican Association (HSRA) leaflets in the Central Assembly (in

association with Batukeshwar Dutt)

on April 8, 1929, and, then voluntarily offering himself for arrest with a view

to highlighting the audacity of the Viceroy in enacting the Trade Disputes and

the Public Safety Bills, even though these had been rejected by the house, read

like adventurous tales.

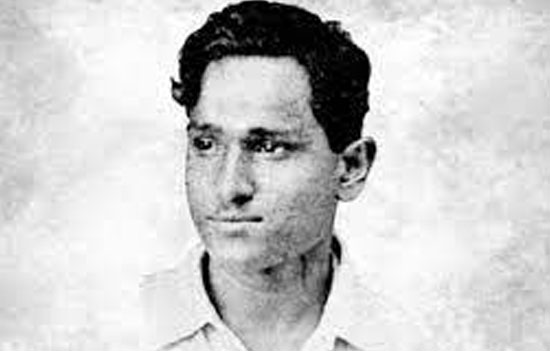

Batukeshwar Dutt is hardly remembered in India.

Batukeshwar Dutt is hardly remembered in India.

The leaflets thrown in the Central Assembly read thus:

“It takes a loud voice to make the deaf hear. With these immortal words uttered on a similar occasion by Valliant, a French anarchist martyr, do we strongly justify this action of ours.... Let the alien bureaucratic exploiters do what they wish. But they must be made to come before the public eye in their naked form... We are sorry to admit that we who attach so great a sanctity to human life, we who dream of a glorious future, when man will be enjoying perfect peace and full liberty, have been forced to shed human blood. But the sacrifice of individuals at the altar of the great revolutions that will bring freedom to all, rendering the exploitation of man by man impossible, is inevitable. Long live Revolution.”

Who

except Bhagat Singh could organise his ranks and fight the obduracy of the

British Raj even when in jail, resort to 64-day hunger-strike along with fellow

revolutionaries, Batukeshwar Dutt (1910-65), Jatin Das (1904-29), Ajoy Ghosh,

Shiv Varma, Des Raj, Kishori Lal and others, in protest against some inhuman

clauses in the Jail Manual, and the high-handedness of those in authority who

had tried to break the morale of satyagrahis by resorting to forced feeding?

Who else could win the admiration even of his detractors for transmuting vague

national feelings into a mass upsurge against the alien regime? Who else could

disdain all the attempts of his sympathisers to get his death sentence commuted

or waived off and, who else could even take his worthy father to task for

revelling in sentimentality?

“My life is not so precious - at least to me - as you may probably think it to be. It is not at all worth buying at the cost of my principles”, he wrote: “This was the time whe n everybody’s mettle was being tested. Let me say, father, you have failed. I know you are as sincere a patriot as one can be. I know you have devoted your life to the cause of Indian independence; but why at this moment, have you displayed such weakness, I cannot understand.”

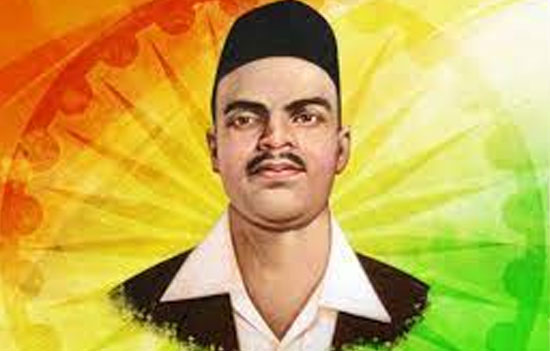

Rajguru was from Maharashtra.

Rajguru was from Maharashtra.

March 23, 1931. The Central Jail

of Lahore (now in Pakistan) hummed with routine activity but towards the

evening, eerie silence fell all over when the word spread that Bhagat Singh

along with his two associates, Shivram Rajguru (1908-31) and Sukhdev Thapar

(1907-31) was to be hanged in accordance with the sham judgment of the Special

Tribunal in the Lahore Conspiracy Case.

Video

Lahore Conspiracy Case

explained by Ashimaji-20 minutes

The stoical trio moved hand-in-hand towards the gallows raising anti-imperialist slogans. They embraced the hang-man’s noose as if they were on a honeymoon. Justice died as the wooden plank under their feet was retracted. The attending doctor declared them dead.

Little did anyone realise that they had resurrected in the minds

of millions of their countrymen.

The massive demonstrations against the manner in which the bodies of the revolutionaries were unceremoniously disposed of on the banks of the Sutlej in Ferozepur, and the criticism of Mahatma Gandhi and the Congress for not adequately pleading for the release of the revolutionaries (i.e. making it a pre-condition before signing the Gandhi–Irwin Pact) substantiated this fact.

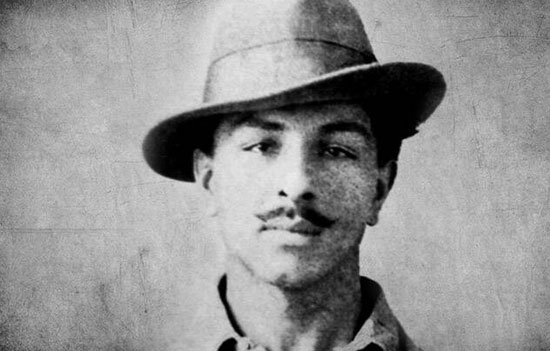

Bhagat Singh

Bhagat Singh

Referring to the increasing popularity of Bhagat Singh, an intelligence report mentioned that “for a time he bade fair to oust Mr Gandhi as the foremost political figure of the day”. Mahatma Gandhi ruefully admitted that his plea to the Viceroy to save Bhagat Singh’s life went in vain. But he observed that he was not to blame for it. “I might have done one thing more you say, I might have made the commutation a term of the settlement. It could not be so made. And to threaten withdrawal would be a breach of faith. The Congress Working Committee had agreed with me in not making commutation a condition precedent to truce. I could, therefore, only mention it apart from the settlement. I had hoped for magnanimity; my hope was not to materialise....”

Before his execution, Bhagat Singh had bluntly told the Magistrate in-charge that Indians could embrace death with pleasure for the preservation of their ideals. He reminded one of Danton, a leader of the French Revolution of 1789, who said before being guillotined: “Show my head to the people. It is worth showing”. Addressing himself as if in a soliloquy, he observed: “Danton! No weakness.”

Even though a fire-brand revolutionary cast in the mould of a Mazzini or a Garibaldi Bhagat Singh disapproved of violence that was brutal in nature and brought travails in turn. “We hold human lives sacred beyond words and would soon lay down our lives in the service of humanity than injure anyone else,” he told the Lahore High Court, in a joint statement with Batukeshwar Dutt. “Unlike mercenary soldiers of imperialist armies who are disciplined to kill without compunction, we respect and insofar as it lies in us we attempt to save human life. Bhagat Singh clarified that the purpose of throwing bombs in the Assembly was only to “awaken England from her dreams” as Chittaranjan Das had once observed, and not to splash blood all over.

According to him, Indian Parliament symbolised “the over-riding domination of an irresponsible and autocratic rule”, and it existed only “to demonstrate to the world the Indian humiliation and helplessness”. It had ignored the interests of a sizeable section of society, humiliated the representatives of the people by “trampling underfoot” the resolutions passed by them, endorsed “repressive and arbitrary measures’’, and prepared the ground for the wholesale arrest of trade union leaders. There was thus no justification for the existence of an institution, which, “despite all pomp and splendour organised with the hard-earned money of the sweating millions of India”, was “only a hollow show”.

Obviously, Bhagat Singh had diagnosed the malady afflicting his motherland. During his trial he took the British government to task for depriving “the starving and struggling millions” of their primary right to promote “their economic welfare”. “None who has felt like us for the dumb-driven drudges of labourers could possibly witness this spectacle with equanimity, none whose heart bleeds for those who have given their life-blood in silence to the building up of the economic structure of the exploiters, of whom the government happens to be the biggest in the country, could repress the cry of the soul agonising anguish which is so ruthlessly wrung out of our hearts.”

Bhagat Singh may not have agreed with Leon Trotsky (1879-1940) that “revolution operates like war; it kills individuals, and puts fear into thousands”, but he was convinced that the idea of elimination of force from the face of the earth was utterly utopian. That should not be taken to mean that Bhagat Singh ever offered an apology for violence like Mikhail Bakunin (1814- 1876) and his followers, about whom Karl Marx and Engels had once said: “What terrible revolutionaries! They want to annihilate everything....These little brainless people puff themselves up with horrifying phrases to appear revolutionary giants in their own eyes.”

Sukhdev was part of the 3 some who was hanged.

Sukhdev was part of the 3 some who was hanged.

Revolution, for Bhagat Singh, was something natural as he

intended to rid himself of exploitation and create a new social order. It was the law of the world, “the secret of human progress,” the means to change “the present order of things based on manifest injustice” and “the inalienable right of mankind.” It did not necessarily involve “sanguinary strifes” nor had it any place for “personal vendetta.”

It was definitely not “the cult, of the bomb and the pistol” but a social process which culminated in the eliminations of both imperialists and capitalists. Bhagat Singh regarded the capture of state power necessary for bringing about a revolution. To achieve this, the involvement of the masses was a prerequisite.

The masses could be awakened by individual acts of sacrifice. In his statement before the Delhi court, he said: “To the altar of this revolution we have brought our youth as incense, for no sacrifice is too great for so magnificent a cause .We are content to await the advent of revolution”.

Hindustan Socialist Republican Association (Hindustan Republican Association until 1928) with which Bhagat Singh was closely associated had clearly stated in its manifesto that the youth could bear “the most inhuman torture smilingly and face death without hesitation as the entire history of human progress was “written with the blood of young men and women”.

Bhagat Singh’s concept of revolution has socialistic overtones. He believed in the sovereignty of the people and wanted to ameliorate the lot of the poor and the tortured sections of society even though he did not live long enough to wipe out their tears. His confirmed belief was that the exploiters were, at best, sitting on a volcano and the time was coming when the citadel of their power would collapse like a pack of cards. Bhagat Singh’s concern for the depressed sections of society is well expressed in this statement which he made before the Delhi court:

“Producers or labourers, in spite of being the most necessary element of society are robbed by their exploiters of the fruits of their labour and deprived of their elementary rights. On the one hand, the peasants who grow corn for all starve with their families; the weaver who supplies the world-markets with textile fabrics cannot find enough to cover his own and his children’s bodies. Masons, smiths and carpenters who rear magnificent places live and perish in slums. On the other hand, capitalists, exploiters, parasites of society squander millions on their whims.... Unless.... the exploitation of man by man and of nation by nation....is brought to an end the suffering and carnage with which humanity is threatened today, cannot be prevented....”

But

Bhagat Singh was no catchword hero or arm-chair revolutionary. He was clear

about his goal and the means to achieve it. Despite

his socialistic leanings, he did not join the ranks of the leftists.

Likewise, his love for humanity did not land him in a religious cradle (his

respect for Arya Samaj, notwithstanding).

Bhagat Singh knew how to stand on his own without the crutches of ideologues or political demagogues. He did not either believe in unprincipled violence. “Force when aggressively used is violence and is, therefore, morally unjustifiable. But when it is used in the furtherance of a legitimate cause, it has its moral justification....The new movement which has arisen in the country....is inspired by the ideals which guided Guru Govind Singh and Shivaji, Kamal Pasha and Riza Khan, Washington and Garibaldi Lafayette and Lenin.”

Bhagat

Singh was a voracious reader and had as much liking for Sanskrit and Urdu as

for Punjabi, his mother tongue. He could imbibe the gospel of a peripatetic or

a Hobbesian with the same ease as the dialectical materialism of Karl Marx.

Although

he proclaimed that his religion was desh-bhakti or service of his motherland,

he was, in no sense, a chauvinist and envisaged the creation of a world

federation which would redeem humanity from the bondage of capitalism and the

misery and perils of wars.

Bhagat Singh is not merely a historical personage for he survives in the values which he ardently professed throughout the course of his life. He does not belong to any particular sect, group or community, for he is much above man-made distinctions. He is the pride of the whole mankind. Let not anyone tag a label to Bhagat Singh’s name for labels may suit lesser men like us who are self-seeking. myopic in outlook and cramped in mental vision.

This article was first published in the Bhavan’s Journal, 15 April 2010 issue. This article is courtesy and copyright Bhavan’s Journal, Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, Mumbai-400007. eSamskriti has obtained permission from Bhavan’s Journal to share. Do subscribe to the Bhavan’s Journal – it is very good.

Author Dr Satish K

Kapoor,

former British Council Scholar,

Principal, Lyallpur Khalsa College, and Registrar, DAV University, is a noted

educationist, historian and spiritualist.

Also read

1.

The

Triveni Sangam of the Independence Movement in Tamil Nadu

2.

VP

Menon the man who saved India

3.

Veer Surendra Sai – Freedom Fighter from Orissa

4.

Life

Story of Sardar Patel

5.

How the INA contributed to India’s Independence

6.

Karnataka Goddess of Courage – Kittur Rani

7.

Who

was responsible for Partition

8.

Did

Ahimsa get India freedom?

9. Lal Bal Pal – The Tridev of India’s Independence Movement

10. Freedom

Struggle in Punjab

11. Lala Lajpat Rai gave a fillip to India’s Freedom Movement