- How to become happy per Vedanta? For that know Different Types of Joys, 3 types of Spiritual Joy and Bliss of Joy.

Human life is a constant struggle to find joy or happiness. It is one of the most fundamental impulses in all human beings. Chandogya Upanishad says: ‘It is for happiness alone that living beings make efforts, whatever possible.’1 The driving force of all human endeavours is but the thirst for happiness. All living beings survive on this earth as long as they get some kind of joy. That is why Taittiriya Upanishad goes to the extent of declaring: ‘Who would have ever breathed without that (bliss)?’2

In layman’s language, this idea can be expressed thus: When our desires are fulfilled, a kind of joy is felt, which has been known by several words like pleasure, happiness, enjoyment, elation, gladness, and so on. In this world, we run towards enjoyments throughout our lives without properly knowing what is the source of joy and understanding the science behind it. If pleasure is in objects, then everyone should get the same amount of pleasure from them. But it is not the case.

Figure A

Figure A

Different

Types of Joys

Pleasures can be

broadly classified into three types as shown in Figure (A), as pointed out by

Vidyaranya Swami in his Panchadashi.3

They are as follows:

(i) Vishayananda, Sensual Joy: It includes

the joy derived from the five sense organs like smell, sound, touch, form, and

speech. It is the happiness resulting from the fulfilment of the desire with

the contact with external objects.4

In order to obtain

worldly enjoyments, one should have a healthy and strong body, young age and

all the objects of enjoyment.5 Bhartrihari says that even all the objects in the world put together cannot satisfy the needs of a single person. Even for those who get those pleasures, young age—which is the best period of enjoyment—will not last forever. Moreover, these pleasures take away the vigour of organs as well as the vitality of the human body. The extreme limit of this joy is that of a mighty king, a sovereign of the world, who has all kinds of enjoyments.6

(ii) Vidyananda, Intellectual Joy: The

network of joy is wider in human life compared to that of animals. Sensual joy

is common to both; but in addition to it, a human is privileged to enjoy

intellectual and spiritual happiness as well. In contrast to sensual joy,

intellectual joy does not give us immediate joy, but is acquired through steady

practice.7 Vidyaranya Swami says

that sensual desire is demonic and is innate in all. However, higher desires

like intellectual desire are obtainable only through the personal endeavour.8 Such personal effort is painful in

the beginning but will be sweet like nectar in the end. It leads to still

higher types of joy, experiencing which, an aspirant finds sensual pleasures

not only insipid but also inferior.

Intellectual Joy

is the joy that makes a scientist spend long hours in the laboratory, a

musician practise daily without break, a scholar study books for hours, and a

person on a telescope gaze at stars and planets for months together. An

ordinary person engrossed in sensual enjoyments can never understand the joy of

such persons, who are engrossed in intellectual pursuits. Swami Vivekananda

says:

Because sense-enjoyments please many, they seek for them, but there may be others whom they do not please, who want higher enjoyment. The dog’s pleasure is only in eating and drinking. The dog cannot understand the pleasure of the scientist who gives up everything, and, perhaps, dwells on the top of a mountain to observe the position of certain stars. … To you, the old sense-things are, perhaps, the greatest pleasure, but it is not necessary that my pleasure should be the same, and when you insist upon that, I differ from you. That is the difference between the worldly utilitarian man and the religious man.9

Again, the

intellectual joy has a very wide range from that of the scientist engaged in

the lab to that of the recluse studying scriptures with the sole aim of

Self-realisation. The highest limit of this joy is experienced by a sage well

versed in scriptures.10

(iii) Brahmananda, Spiritual Joy: when a

person is not satisfied by the intellectual study of scriptures alone but

experiences the truth they teach, he or she becomes the knower of Brahman. The

joy attained by such a person is the highest of all and it does not fade with time

or place.

This spiritual joy

can further be divided into three types depending upon the advancement of

spiritual aspirants (Figure A).

Yogananda, Joy

of Yoga: It is the joy of cessation of all desires. According to Upanishads,

the steady control of the senses is considered to be Yoga.11 The aim of Yoga is the cessation of all the normal activity of

the five sense organs and the mind. According to Sage Vyasa, the highest joy

gained on this earth or in heaven is not even one-sixteenth part of this joy.12

Atmananda, Joy of the Atman: When the desires are fully controlled or annihilated, one comes to know one’s real nature, that is, the Soul (Jivatman). It is the indicator of the experience ‘I Am’, and witnesses three states of consciousness-jagrat, Svapna, and suṣupti;

waking, dream and deep sleep-and is also separate from panchakoṣas, five sheaths-physical, vital energy, mental,

intellectual, and blissful.13

Advaitananda, Joy of Non-Duality: In this state, one experiences the same Reality everywhere. Yogananda and Atmananda are restricted by time and place. One can have Atmananda only in samadhi and not always. Desires also can crop up in the mind at different times and places which will lead to problems for the spiritual aspirants. So, it is said: ‘Yo vai bhuma tat sukham-infinite alone is the (real eternal) bliss.’14

However, Advaitananda transcends the barrier of time and space. This boundless

and endless joy has four characteristics:

Absence of sorrow

(dukhabhava)

Fulfilment of all

desires (kamapti)

Accomplishment of

all deeds (kritakritya), and

Achievement of all

that is to be achieved (praptaprapya).15

Upanishads claim

that for such a person, who has attained Advaitananda, there can never be any

delusion and sorrow.16

Nature

of Tamasik and Rajasik Persons

To the above

mentioned three kinds of joy, Bhagavan Sri Krishna in Bhagavadgita adds one

more: the joy of sleep, sloth, and laziness, which is of tamasik or ignorant

nature.17 Such a person goes to sleep or remains inactive most of the time. It deprives one of right judgement and subjects one to doubt, dullness, and uncertainty. Such a condition of inertia finally results in the wastage of one’s life. Sensual enjoyments are rājasik in nature.18

The persons

engaging in them have too many goals in life, which keep on changing with time.

A rajasik person will not have a definite goal like a sattvik person. His or

her energy, not being focused, is scattered away in many directions. The rajasik

joy, which arises from the contact of the senses with their objects, engages

one in intense activity. It is like nectar while enjoying, but becomes like

poison in the end. Also, ceaseless activities of this nature give rise to

ambition, lust, anger, avarice, arrogance, egotism, envy, pride, jealousy, and

so forth. This leads one to the loss of strength, vigour, complexion,

intelligence, wealth, and wisdom.

Progression

of Joy

Intellectual joy is rajas mixed with sattva. The percentage of sattva keeps increasing from Yogānanda to Atmānanda. In Advaitānanda, what we will find is śuddha sattva, pure sattva. This turns out to be a real friend in one’s effort to realise Truth. Śuddha sattva manifests itself in a person in the form of humility, guilelessness, unselfishness, contentment, faith, devotion, and leads one to purity and self-control.

As a matter of fact, in all human beings, there is always an urge to seek higher forms of happiness. Sri Shankaracharya says: ‘Sarvo hi upari

upari eva bubhūṣati lokah—everyone aspires to higher and higher forms of joy.’19

The higher forms

of joy are potent even in the most sensual persons. However, they may not find

immediate expression of higher joy due to their strong sensual passions. But in

due course, as one progresses in spiritual life, the higher joys will get

manifested.

It is a rule that

any sensual pleasure, pushed beyond a certain limit, ends up in satiety and one

develops disgust for it. So sooner or later, everyone will develop dispassion

for sensual pleasures. Such dispassion finds expression in the form of

practising ethical values like truth, goodness, and charity. But later, when

the dispassion finds its highest expression in spirituality, the person will

not get satisfied by the moral life alone. Sri Ramakrishna would say in this

context:

What are you

talking about? People talk about leading a religious life in the world. But if

they once taste the bliss of God they will not enjoy anything else. Their

attachment to worldly duties declines. As their spiritual joy becomes deeper,

they simply cannot perform their worldly duties. More and more they seek that

joy. Can worldly pleasures and sex pleasures be compared to the bliss of God?

If a man once tastes that bliss he runs after it ever afterwards. It matters

very little to him then whether the world remains or disappears.20

The same idea is

echoed by Swami Vivekananda also when he says:

The going from

birth to death, this travelling, is what is called Samsara in Sanskrit, the

round of birth and death literally. All creation, passing through this round,

will sooner or later become free. ... It is true that every being will become

free, sooner or later; no one can be lost. Nothing can come to destruction;

everything must come up. ... The vast masses of mankind are content with

material things, but there are some who awake, and want to get back, who have

had enough of this playing, down here. These struggle consciously, while the

rest do it unconsciously.21

Without getting a

taste of spiritual joy, one cannot give up sensual enjoyments completely.

Hence, Sri Ramakrishna prayed to the Divine Mother to make devotees who visited

him also experience divine ecstasy at least to some extent.

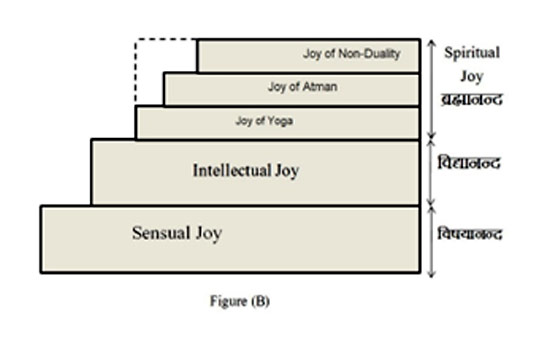

Figure B.

Figure B.

Bliss

of Brahman

Whatever happiness

experienced by us in this world comes from Brahman alone (Figure A). This is

the clear dictum of Upanishads and of Vidyaranya Swami, the author of

Panchadashi. However, Brahmananda, the bliss of Brahman can be felt by a Jnani alone.

It is because an aspirant (sadhaka) elevates oneself from sensual to

intellectual and then to spiritual, step by step (Figure B). Happiness

experienced in all these stages are but a reflection of the bliss of Brahman;

but only a fraction of it is experienced in the sensual and intellectual

planes. However, when vrittis, mental modes are directed inward and withdrawn

from the external objects, the bliss of Brahman flows unobstructed.22

In this state, the

highest bliss (bhuma) is experienced. In Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, sage Yajnavalkya instructs king Janaka: ‘This is the supreme attainment, this is the supreme bliss, on a particle of this very bliss or on a fragment of this, other beings live.’23

The person who is

satisfied with joy derived out of sensual pleasure is like a person attempting

to read a book in a dim light coming through three or four big sheets of misty

glass. An ancient text called Paramartha Sara says that it is ‘like a thirsty person immersed in the ocean, who neither sips it nor even looks at it. But when far off mirage water is seen, he runs towards it to satisfy his thirst. The whole life is being spent running like this. Lo! How mysterious is this situation!’24

We run after

sensual or intellectual enjoyments until we get a glimpse of spiritual joy.

Without tasting this bliss, however, we may try to control the senses-a longing

for these enjoyments or a pull of sensuality called rasa 25 in Bhagavadgita

will always remain in our mind and will keep on tormenting us. However, after

having tasted the bliss of Brahman, the reality of all inferior joys would be

exposed bare and the source of all the joys is known like a crow,26 which has a single pupil that moves

between the right and left eyes depending on the requirement. In the same

manner, a knower of truth clearly experiences such a state where one is aware

of the fact that all joys originate from Brahman alone. In that state, the

lower forms of joy can never befool a Jivanmukta,

a realised soul as the rasa or the taste for them 27 is gone forever. He will then experience all these pleasures indifferently and sorrows no more torment him. Jivanmukta will always be immersed in the bliss of Brahman and this is the ultimate fulfilment one can have in one’s life in this world.

This article was first published in the June 2022 issue of Prabuddha Bharata, monthly journal of The Ramakrishna Order started by Swami Vivekananda in 1896. This article is courtesy and copyright Prabuddha Bharata. I have been reading the Prabuddha Bharata for years and found it enlightening. Cost is Rs 200/ for one year and Rs 570/ for three years. To subscribe https://shop.advaitaashrama.org/subscribe/

References

1. ‘Yada vai sukham labhate atha karoti’ (Chandogya Upanishad, 7.22.1).

2.

Taittiriya Upanishad, 2.7.1.

3.

Panchadashi, 11.11.

4.

Panchadashi, 11.86.

5.

Taittiriya Upanishad, 2.8.1.

6.

Panchadashi, 11.51.

7.

Bhagavadgita, 18.36 (abhyasad ramate

yatra...).

8.

Swami Vidyaranya, Jivan Mukti viveka,

trans. Swami Mokshadananda (Advaita Ashrama, 2019), 89.

9.

The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda, 9 vols (Calcutta: Advaita Ashrama, 1–8, 1989; 9, 1997), 2.16.

10.

Panchadashi, 11.52.

11.

Katha Upanishad, 2.3.11.

12.

Vyasa’s commentary on Yoga Sutra 2.42.

13.

Vivekachudamani, verse 125 (avastha-traya sakṣi

san panca kosa vilakṣaṇah).

14.

Chandogya Upanishad, 7.23.1.

15.

Panchadashi, 14.3.

16.

Isha Upanishad, 7.

17.

Bhagavadgita, 18.39.

18.

Bhagavadgita, 18.38.

19.

See Sri Shankaracharya’s commentary on the Katha Upanishad, 1.1.28.

20.

M, The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna, trans.

Swami Nikhilananda (Chennai: Ramakrishna Math, 2002), 756.

21.

Complete Works, 2.259.

22.

Panchadashi, 15.19.

23.

Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, 4.3.32.

24. Paramartha Sara of Adi Shesha, verse 2.

25.

Bhagavadgita, 2.46.

26.

Panchadashi, 11.128–29,

kakakṣivat.

27.

Bhagavadgita, 2.59.