- Article is about Prambanan Temple, Candi Ceto-Dieng Plateau and Lontar temples.

With Abundant Fertile Land Yielding Three Rice Crops a year, Indonesia has historically been an agriculturally prosperous region—as it continues to be. We can get a sense of the great investment in religion the kingdoms of centuries ago made from the Prambanan temple and the Buddhist Borobudur monument, two lavish complexes located just a few kms apart in central Java, possibly built by the same king. We omitted these historical sites from last issue’s accounts of the Hindus of Java because as they unfortunately no long figure much in the lives of the island’s Hindus. They are today popular tourist destinations and remain a remarkable testament to a past era.

This article is "Courtesy Hinduism Today magazine, Hawaii".

We find References to Java in HINDU literature as early as 200 bce; the oldest Hindu relic discovered there to date is a first-century-ce statue of Ganesha found on Panaitan Island, off the northwest coast of Java near Jakarta. Throughout the first millennium of our current era, successive Indian kingdoms—the Palavas, Guptas, Palas, Cholas and others—spread Indian culture across Southeast Asia, including what is modern Indonesia.

Hinduism

was brought here first by Hindu traders. Buddhism, still strong in India at

that time, was brought by pilgrims passing through on their way to and from

India, and by Chinese missionaries.

The two religions

harmoniously coexisted to the extent that both Hindu and Buddhist temples,

including some of the most magnificent on the island, were built by the same

Javanese kings. But Java is a seismically active region with numerous

volcanoes, with eruptions and frequent earthquakes through the centuries, some

of devastating magnitude. Even immense stone structures do not hold up under

such conditions.

By the mid-19th

century, shaken apart by earthquakes, the temples were in unfortunate

condition. Stones and other materials have also been looted from the

structures. And the seismic unrest continues: as recently as 2006, an

earthquake caused substantial damage to Prambanan Temple.

Reconstruction

programs have been conducted at the most prominent temples, first under the

Dutch in the 1930s and then under the government of Indonesia, continuing to

this day. This is no easy task. Essentially the original structures were

largely collapsed, with hundreds of stones scattered around the area, some

buried beneath the soil. Parts of monuments were below the current ground

level, particularly at Borobudor. The government specified that before any

shrine could be rebuilt, at least 75 percent of the masonry must be found and

identified and their position in the temple schematic determined. Of smaller shrines only the foundations are visible.

The results of the restorers’ valiant efforts are mixed. They neither possessed the skills of the original builders nor did they try to recreate each temple exactly as it had been. Aware of their own limitations, they simply tried to piece structures back together as best they could and fill in what was missing.

It is understandable, therefore, that most of these structures are no longer active places of worship. In fact, Indonesians refer to them as “dead monuments”—as opposed to the “living monuments” of Bali, the ancient temples there where worship has never ceased. Although puja is performed from time to time in the dead monuments, their primary use is by the tourist trade. Indeed, they are very popular with Indonesians and international travellers alike.

Our April, 2014, tour

of Java had two objectives: to meet the local Hindu community, as reported in

the October/November/December, 2014, issue and to explore these old temples,

the subject of this report.

In particular, we visited several in Central Java, including the largest and best known, Prambanan, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. From there we went to the site called Ratu Boko’s Palace-the residence of a king that commands a stunning view of Prambanan Temple. We then visited Ceto, built in the 15th century and quite different from Prambanan. Finally we explored the Dieng Plateau temples, the island’s oldest Hindu temple complex, dedicated to the

principal figures in the Mahabharata. Our report concludes with the 9th-century Borobudur temple, Indonesia’s most popular tourist attraction and the largest Buddhist temple in the world. Map of Java showing the four temples covered in this report.

Map of Java showing the four temples covered in this report.

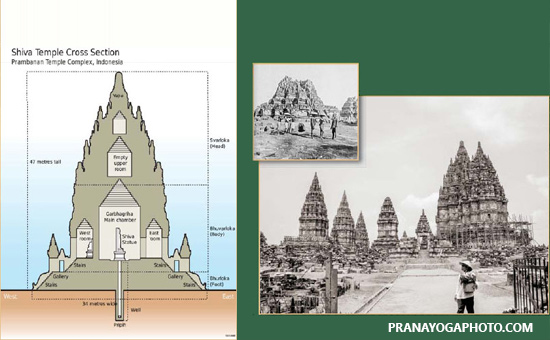

Diagram of the main Siva temple; repairs underway shortly after the 2006 earthquake; (inset) the partially collapsed central Siva temple around 1895, after its rediscovery by the British.

Diagram of the main Siva temple; repairs underway shortly after the 2006 earthquake; (inset) the partially collapsed central Siva temple around 1895, after its rediscovery by the British.

Prambanan“Prambanan,” explains archeologist Manggar Sarl Ayuati, “is one of the largest Hindu temple complexes in Asia with an enclosed area 390 meters on a side. It was built in 856 by King Rakai Pikatan of the Sanjaya dynasty, which ruled the Mataram Kingdom, and was expanded by later kings. It is dedicated to Siva.”

Prambanan has three

concentric courtyards. The innermost contains 16 temples, including the 156-foot-high main temple to Siva and 108-foot temples to Vishnu and Brahma. Each is faced by a smaller temple for the God’s vahana (mount): Nandi the bull for Siva, Hamsa the swan for Brahma and Garuda the eagle (Indonesia’s national symbol) for Vishnu. Scenes from the Ramayana and the life of Krishna are carved on the

outer walls of the temples. The Siva temple has multiple chambers - Siva in the center, Durga in the north, Rishi Agastya in the south and

Ganesha in the west.

The second courtyard

originally contained 240 small temples; only 129 have undergone any degree of

restoration. The rest are just piles of rocks. No structures remain in the

third courtyard, and the historical use of that area is unknown. The complex

also contains four Buddhist temples, built by a Hindu king for his Buddhist

wife.

Prambanan was

abandoned in the 10th century, likely when the Mataram kingdom moved to East

Java following a huge eruption of nearby Mount Merapi that covered the entire

area in volcanic ash. A major earthquake in the 16th century collapsed the

upper parts of the main structures. The temple sustained additional damage in

the 6.5-magnitude earthquake of 2006. Repairs were still underway during our

2014 visit.

I was saddened to

hear this spectacular place referred to as a dead monument and to see it

reduced to a picnic spot for tourists. Puja is performed here only once a year,

but that brings thousands of people from all over Indonesia to worship Siva,

Brahma and Vishnu. With some difficulty, puja can be arranged at other times of

the year. Our guide, Pak Dewa Suratnaya, a journalist with Media Hindu magazine, said

strongly that these great temples should be brought to life again through

regular worship. I agreed with him wholeheartedly.

Ratu

BokoTwo miles away, commanding a spectacular view of Prambanan, lies Ratu Boko’s Palace. This forty-acre complex of buildings and fortifications was likely built by the same kings who built Prambanan. An inscription found in the ruins during restoration has been dated to 792 ce.

One enters Ratu Boko through a grand staircase (photo below), beyond which are pavilions, audience halls, three miniature temples, what is believed to be a crematorium, a terrace with multiple pools of water and at least two major artificial caves, apparently built for meditation. A gold plate found here carries the inscription “Om Rudraya namah swaha,” a prayer to Siva in His Rudra form. There is also evidence here of Buddhist worship. A good three-part video on Ratu Boko can be viewed at bit.ly/RatuBoku

Candi CetoThis 15th-century

Siva temple is located on the western slope of Mount Lawu at an elevation of

about 3,000 feet, on the border between central and east Java. The 62-mile

drive from our hotel in Klaten took us over three hours.

One of several temples in this area, Candi Ceto is among the last built by the Hindu kings. In appearance it is much different from Prambanan. By this time, six centuries after the construction of Prambanan, the Javanese Hindus had developed an architectural style that diverged from the traditional Indian design and motifs found in the earlier temples. Furthermore, when Ceto was renovated in 1975-76, some “reconstructions” were made that were not justified archeologically and were not part of the original structures. An example is the several tall split or winged gates. Although these are a defining element of Balinese temples today, there is no evidence that they were a part of the original architecture of Candi Ceto. But even if not historically authentic, the gates provide a soul-stirring impact.

A signboard posted at

the site tells us that the temple has 13 terraces from its base to its

peak, reminiscent of the prehistoric Javanese structures. At the entrance is a

large stylized stone turtle; other animals are depicted throughout the area.

The various statues found here appear to represent humans rather than Gods.

Candi Ceto has its

own worship schedule. Puja is performed every fifth day by 50 devotees and

priests. A special ceremony is held every seventh five-day cycle, called Angora

Kasi on the Javanese calendar. Because of the active worship, this remains a

spiritually charged place; but it is also a popular tourist destination. Many

people were here simply to enjoy the cool, pleasant weather and beautiful

scenery.

Dieng ComplexWe stopped to explore the Dieng Plateau of north central Java on our way to the Semarang airport, but one of the island’s frequent rainstorms descended upon us and we quickly resumed our journey. This is the oldest set of temples in Java, dating to the seventh

century and likely among the first built with Indian design and technology.

Today the temples are named after principal characters in the Mahabharata, but little is known

about their original purpose nor the king who built them.

Archaeologists believe the designs to be in the

Dravidian and Pal lava style of South

India. They are grouped in irregular clusters, named today as Arjuna, Gatotkaca

and Dwarawati. The original site may have included as many as 400 temples, of

which only eight remain standing. When they first came to the attention of a

British soldier in 1814, they were in the middle of a lake. The Dutch East

Indies government undertook their restoration in the mid-nineteenth century.

Compared to

Prambanan, built just a short time later, everything here is relatively small,

lacking in ornamentation and neither uniform in design nor organized in the

elaborate, concentric mandalas of later temples. It is believed that increased

volcanic activity led to their abandonment in the 10th century, around the same

time as Prambanan.

Lontar (palm-lead manuscripts)One other form of

ancient monument, if you will, is found here in Java: the palm-leaf manuscripts

known as lontar. Written in Sanskrit and Old Javanese, these are clearly sourced in South India’s and Nepal’s Saiva Agamas, among other

scriptures. While hundreds of lontar are known to scholars - many in the library of Leiden University in Holland, as well as

in libraries in Bali and Jakarta - readers may recall

from the previous article that priests I met refused to even show me the lontar

in their possession, considering them sacred and secret. Many other lontar are

believed to have been lost when the Majapahit kingdom fell in the 15th century

and Hindus fled to Bali.

According to scholar Andrea Acri, “These are practical manuals, intended as guides for initiates. They deal with the Saiva concepts of salvation, cosmology, micro/macrocosmic classifications, yoga, mantras, Absolute Reality and the various aspects of Siva.” One known source of the lontar is the Kirana Agama.

A heretofore unknown commentary on Patajali’s Yoga Sutras called Dharma Patanjala has also been

discovered in Java. This is different than the well-known Yogabhasya attributed to

Vyaasa.

The first and second

shloka of Dharma Patanjala, as translated by Acri, reads, “The Lord—unfathomable, formless, appeased, constant, immutable—that is Siva, subtle, supreme, appeased, with form as well as formless. What is called the cessation of the functions of the mind is the yoga, extremely difficult to achieve. Having undertaken that yoga, the soul itself alone shines forth.”

ConclusionAs an Indian, I was

startled to find all these distinctly Indian-style temples built so long ago in

this far-off land. These Hindu kingdoms were not established by conquest and did not involve one racial group ruling over another; these were ethnic Javanese kings, ancestors of the people who still reside here. Through the kings’ interchanges with India, Hinduism and Buddhism were imported wholesale, complete with their mysticism, yoga, scriptures, rituals and architecture. Only now, in the 21st century, are we again seeing a similar exportation of Hinduism from Mother India, with huge and elaborate temples being established in distant lands.

First published in Hinduism Today. To read article with all pictures click here

Also see

1. Prambanan

Temple Java

2. Mother

Temple Bali

3. Naga

Temple Batam

4. Meet

Hindus of Java