- Read why Indic culture ended in Khotan, Legacy

of Indian Masters, Contribution of Sanskrit texts in cultural development, Arts

and Architecture, Performing Arts of Central and to an extent East Asia, Buddhist

sutras for State Protection.

This was the topic of an International seminar organized by the Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan in New Delhi. Papers presented have now taken the form of a book. We present book introduction in smaller parts. Note “Central Asia is a region in Asia which stretches from the

Caspian Sea in the west to China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan

and Iran in the south to Russia in the north, including Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan-Editor.

History (1st – 13th century): An Age of Harmony, Beauty and Wisdom

How

did Buddhism gain its foothold in such a remote part of the world and what

forms of expression did this religion develop in these out of the way places? A

precise chronology of the important events and achievements of the great

scholars, active in the kingdoms of Central Asia provide mile-stones for a

study of their cultural heritage and chronology of their relations with India.

Sequence

of movements of traders and pilgrims, scholars and missionaries, their major

activities, their travelogues provide a broad base to the study in historical

perspective. Inscriptions and art styles are equally important for a

comprehensive study of evolution and development of various sects in Central

Asia and beyond. text-indent:0cm'>Power

struggle went on for centuries among the Chinese, Uigurians, Turks, Tibetans

and others. In the ninth century Chinese Central Asia was predominantly

controlled by the Uigurians. Around the beginning of the second millennium the

monasteries began to become victim of destruction. Arabs were threatening.

Khotan was attacked several times. With the decisive victory of Islam in the

tenth century Kashgarh was converted to Muhammadanism.

This

marked death knell to the classical traditions and arts of Central Asian

kingdoms. In a few centuries beauty of paintings, elegance of sculptures,

wisdom contained in the scriptures buried under sand. Sand in the desert

preserved the cultural heritage and history of Indo-Central Asian cultural

intercourse for centuries.

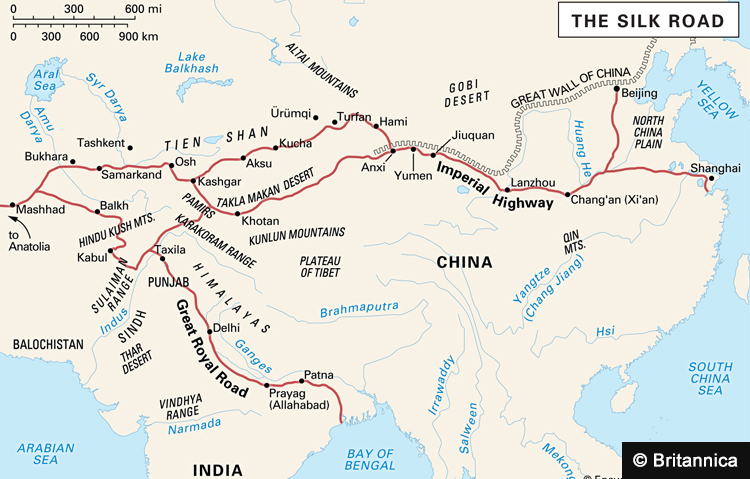

See route to China through Xinjiang.

See route to China through Xinjiang.

Scholar pilgrims: Life and Legacy of Indian Masters

A tradition holds that the first

translation of Indian scriptures in Chinese occurred during 246-219 B.C., the

reign of Chin dynasty, when eighteen wise men carried the scriptures from India

to China. But the exact and official date given in an inscription at the White

Horse monastery, of the first Indian teachers going to China is A.D. 67, when

two Indian scholars-Kasyapa Matanga and Dharmaraksa had reached there on an invitation of

the King Ming Ti of the Late Han dynasty. They settled in Loyang initiated

translation activities.

From then onwards there was an unbroken tradition of teachers going to China. They translated Sanskrit texts beginning from the first century. Loyang was one of the vibrant centers of Buddhist learning. 359 texts were translated by twelve translators who were active at a monastery there, during the Han supremacy, in the first to third century A.D. Chinese scholars, well versed in Sanskrit were engaged in translation in collaboration with Indian scholars. 176 Sanskrit texts were translated by the most celebrated translator—An-Shih-Kao, a Prince from Parthia. He reached China in A.D. 148 and carried on translation work till A.D. 170.

An Indian Sramana, Vighna was active in AD 224. During the rule of the Western Tsin dynasty, Indian intellectuals were active in the then-capital Loyang. A large number of Sanskrit texts on Mahayana were translated by them. Twelve of those scholars translated 447 works, of which just 153 are extent. Saddharma-pundarika-, Lalita-vistara- and Panca-vinsati-prajna-paramita are the prominent sutras among them. One of the most popular sutras— Panca-vimsati-prajna-paramita- was first translated by Dharmaraksa in 286 and later by Kumarajiva. Asta-sahasrika-prajna-paramita-sutra was translated twice by Kumarajiva in 408 and Lokaksema in 179, in 10 fascicles each. Kumarajiva was so famous for his wisdom that he

was taken as a prisoner by the Chinese.

Statue of Kumarajiva, Kizil

Caves, Kucha, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China. Pic

by Benoy K Behl.

Statue of Kumarajiva, Kizil

Caves, Kucha, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China. Pic

by Benoy K Behl.

Full caption by Benoy K Behl – Kumarajiva,

of the 4th century CE, was the son of the Indian Pandit Kumarayana,

the royal teacher at Kucha. He was married to Princess Jiva of Kucha and their

son was named Kumarajiva, after both their names. At a very young age he was

taken to Kashmir, the land of his father, to learn Sanskrit and Buddhist

scriptures. He returned to Kucha to become the greatest translator of Buddhist

texts into Chinese.

Bodhidharma, the

Indian monk from Kancipuram, transmitted the philosophy of Dhyana, which became popular in China as Ch’an and in Japan as Zen. In Mahayana Buddhism the most systematic treatments of the ten stages leading to enlightenment are offered in the Dasa-bhumika-sutra translated by Bodhiruci in A.D. 508-35. Paramartha, Buddha-bhadra, Siksananda, Dharmaksema, Buddhayasas, Upasunya, Sanghapala, Gunabhadra, Bodhiruci, Gautama Prajnaruci, a Brahmana from Benaras, Narendrayasas, and other prominent teachers from India will be discussed in this chapter.

Contribution of Sanskrit texts in cultural development of

Central and East Asia

The

lost legacy of Indian masters and their contribution in the cultural spheres

can be traced through Sanskrit manuscripts discovered from Afghanistan, Khotan,

Kizil, Turfan, Niya, Dandan Uilik, Shanshan, Dunhuang, and several other

places. The oldest Sanskrit manuscript (Kushana period, i.e. second century

AD), from Qizil in the Turfan area is of the drama Sariputraprakarana by Asvaghosa. Biography of Kalidasa and

fragments of Sakuntala are valuable

documents for studying the impact of Indian drama on the Chinese.

The

echo of six elements of painting in the Kamasutra can be traced in the “Six aspects” of painting established by Hsieh Ho in 490 AD. By the seventh century the Chinese were fascinated by the science of astronomy, calendrical knowhow and mathematics. They were known as P’o-lo-men, or Brahmin books. Gautama Siddha, had introduced the symbol of zero, an early form of trigonometry and other innovations. An Emperor of the T’ang dynasty had sent s mission to Champa to bring their library of 1350 Sanskrit manuscripts as war booty.

Sudhana’s way to enlightenment, painted or drawn on the basis of the Gandavyuha-sutra, was a favorite for the philosophers and artists in China. Sanskrit texts on medicine, astronomy and astrology, written in Brahmi script discovered from Central Asia introduced secular sciences. Hundreds of documents of administrative, commercial and legal use, drafted in Sanskrit surmise the use of Sanskrit as a language of administration.

Buddhist

sutras inspired large scale projects of decorating the caves, i.e. pictorial

representation of Bhaisajyguru-sutra, recited for prolonging one’s life, goes back to the fourth century AD. Sanskrit played the same role in Khotanese medicine, as Latin in the European.

An

interesting document of Indian cultural heritage in Central Asia is the

so-called Bower manuscript that contains seven medical texts. Other texts related to medicine are--Jivaka Pustaka

and Siddhasara etc. The ancient sites at and near Khotan have also yielded

Khotanense texts of Amitayurdhyana-sutra,

which was recited for long life and has inspired painters from Dunhuang to

Japan.

Sanskrit

was taught at the monasteries in Kucha. After learning Brahmi alphabet, a

student had to study Sanskrit grammar according to the Katantra system. The

Germans discovered a text from the Turfan Oasis in which verses are composed in

meters like Sikharini, Vasantatilaka and Praharsini. Such texts introduced new

style in poetics.

Art and Architecture

Outstanding

works of art and architectural remains discovered from various sites, supply

invaluable information about their contemporary culture. The findings show that

Kucha was a center of Hinayana Buddhism and Turfan of Mahayana school of

Buddhism. Fahien has stated that each family of Khotan had its own domestic

chapel with a stupa. text-indent:0cm'>According to Fahien the king’s New Monastery, which was one of the grandest monasteries of Central Asia was constructed in eighty years. Many of the temples were adorned with Chinese, Turkish and Indian inscriptions and magnificent frescoes. Sculptures and paintings illustrate intermingling of the art of China, India and Persia, and indeed with that of Greece and Rome.

Sculptures

discovered from ancient cities, and once flourishing oasis kingdoms illuminate

in many ways the crosscurrents of iconography and style. They relate the

history of Buddhism traversing the path from the Northwest frontiers of the

then-India to China, Korea and Japan. The images are of divine beings, of

Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, protectors, benefactors, guardians, eight classes and

sravakas etc. for purity and

perfection resulting from punya/merits and jnana/knowledge.

Paintings and drawings were done on paper, silk or walls. Inside the caves, paintings and sculptures intermingle to create the most glorious scenes. Empty niches of today, once housed images of great beauty. Hell scenes were awe-inspiring, they were meant to instill a sense of virtue in the minds of the devotees. Buddhist texts served as source books for paintings.

See Kashghar & adjoining countries as of today.

See Kashghar & adjoining countries as of today.

Buddhist philosophy as a Way to Higher Aspirations of Life

Mahayana

found its highest expression in East Asia. Its life friendly concepts were the

basis of several sutras. Satya, truth has motivated Buddhists at all times and

in all climes. Refraining from untrue speech is one of the five fundamental

vows (pancasila). It is often chanted at the Buddhist activities. Pancasila was the basis of the first constitution of Japan

created by Prince Shotokutaishi in the seventh century. The text

Satyasiddhi gave a foundation to the Jojitsu sect in Japan.

For the Chinese, gaining spiritual merit by secular acts was a new concept, which came with Buddhism. Other social ideals like sunyata and paramita became popular with Bodhisattvayana.

Zen became the culmination of Buddhist art in East Asia. The

Indian teacher Bodhidharma had carried the philosophy of dhyana to East Asia which is known as Ch’an in China and Zen in Japan. Or saying the other way, it is a product of the Chinese and Japanese soil from the Buddhist seed of Enlightenment.

The

Heart Sutra provides the dictum of Zen art: Form is Emptiness, and Emptiness is

Form (rupam eva sunyata, sunyata eva

rupam). The diaphanous colours and the blank spaces in a Zen painting echo

this relativity of form and emptiness. The perfect whole of Zen aesthetic

expression possesses seven characteristics: asymmetry, simplicity, austere

sublimity, naturalness, subtle profundity or profound subtlety, freedom from

attachment and tranquility.

Ahimsa has permeated the social -lives in China and Japan. The Chinese have written poems and drawn sketches on Ahimsa. It is non-violence both in mind and deeds. It was conveyed to the people of China in four Chinese renderings of the Udanavarga which was translated from the original Sanskrit text of Dharmatrata by the Chinese monk Chu Fo-nien in collaboration with Sanghabhuti a monk from Chi-pin (Kabul) in A.D. 3741, under the title Ch'u yao-ching.

This version was reworked into pentasyllabic verse under the title Fa-chi-yao-sung-ching, in A.D. 985 by T'ien Hsi-tsai who had come to China from Kashmir (var. Jalandhara). In the Sino-Japanese school of the Abhidharmakosa (Kusha-shu), ahimsa is one of the ten basic good functions (kusala-mahabhumika) which arise when a virtuous state of mind exists.

According to the Japanese, “It is a mental function which prevents a person from doing disagreeable things to others and injuring them.” Printing flourished as an integral part of Buddhist requirements of large number of sutras and mantras for mass distribution to acquire due merit. Sutras were recited for protection, peace and prosperity of the state. The history of 23 Patriarchs translated by Kekaya & Than–yao in AD 472 lauds the talents of Asvaghosa as a musician and

singer in the service of the Dharma.

Shiva and Parvati, Mural,

Kizil Caves, Kucha, Xinjiang, c. 6th Century CE, China.

Photograph by Benoy K Behl.

Shiva and Parvati, Mural,

Kizil Caves, Kucha, Xinjiang, c. 6th Century CE, China.

Photograph by Benoy K Behl.

Full caption by Benoy

K Behl - Hindu

deities are commonly seen in the art of the Buddhist caves in India and across

the many countries of Asia. We are reminded of the cosmopolitan culture of

ancient times, when Buddhist caves and art were made in the rule of Hindu kings.

Ancient inscriptions also show that the wives of Hindu kings in India quite

often worshipped a Buddha or a Jaina Tirthankara.

Sanskrit inscriptions, Indic Scripts and Calligraphy

Libraries were built for the community living the monastic establishments in Central Asia. They kept huge collections of Buddhist texts copied and translated from Indian manuscripts written in different scripts and languages. At times, the texts are bilingual or even multilingual. Buddhist texts in Sanskrit, Prakrit or local languages, are largely written in Indian scripts-Brahmi and Kharosthi. Sanskrit dramas and texts on medicine, astronomy and astrology, written in Brahmi have also been discovered from Central Asia. Besides them, hundreds of documents are of administrative, commercial, and legal use, drafted in Sanskrit, Prakrit or Central Asian dialects, and written in Indian scripts, as well as common alphabet of the Brahmi script, have been found from various sites. Inscriptions in the ‘Cave of the Painters’ are written in Turkestanian Brahmi of 5th-6th

century. Brahmi has been written in various styles in different regions and

periods.

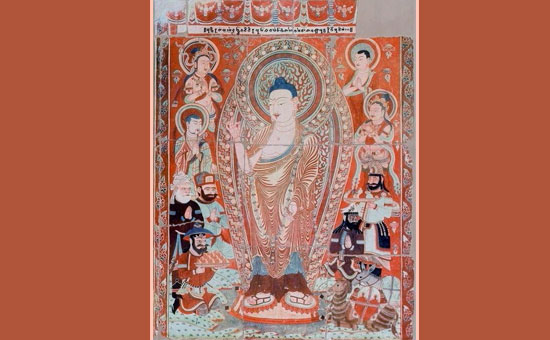

Pranidhi scene, Bezeklik Caves.

Pranidhi scene, Bezeklik Caves.

Sanskrit inscriptions discovered from Central Asia are a rich source of study of epigraphic and our cultural connections. Bezeklik caves were decorated by the Uigur Kings of Turfan. They are the only Central Asian people to have written the donor inscriptions in Sanskrit. The Sanskrit mantra from the Old Turkish-Uigur text ‘Disā-stvustik which is ‘disām sauvastika’ was written on the auspicious and the inauspicious directions for the protection of traveling merchants. A Sanskrit inscription from Loyang, the then capital of China, a centre for translation of Sanskrit texts, erected in AD 1104, discovered by Prof. Raghu Vira in 1955. The script of the inscription is Siddham written from right to left and top to bottom in the Chinese style.

A

text of Dhammpada, written on birch bark, in Kharosthi script of 1st-2nd

century in Prakrit language was discovered from Khotan. The ancient sites at

and near Khotan have also yielded Khotanense texts of

Vajracchedika-prajna-paramita and Amitayurdhyana-sutra, besides quite a few

fragments in the Late Gupta script.

Performing Arts: Dance, Drama and Music

Buddhist

music germinated in the second century in China when Buddhists composed hymns

for the Buddha and Bodhisattvas. Prince and poet Tsao Chih (AD 192-232) is the

first composer according to Buddhist tradition. Once he visited Mount Yu in

Shantung and heard wonderful music of Pancika. He has left more than 3,000

tunes whose melodiousness could only derive from divine inspiration.

According

to the Chinese sources people of Kucha (in modern

day Xinjiang) were fond of Indian music and musicians. Indian music was ta ken to Kucha in ancient times. Many musical subjects decorated the walls of the Central Asian monasteries. Early Chinese records speak about the tradition of music in Khotan: Emperor Wu-ti sent Chang Ch’ien to the west in 138 BC to bring musical instruments and melodies from Kucha. Most probably this melody was of Indian origin. Son-in-law of the Emperor wrote twenty-eight new tunes based on the melody—Mo-ho-tou-le. The tunes were played as military music. Kucha continued this unbroken tradition for centuries.

The Chinese General Protector, Lu Kuang carried away groups of performers—actors, musicians and dancers to China as war booty in AD 382. This resulted in popularity of Indian music in China. Records say that once one of the lute teachers in China, was a Brahmin. Another teacher was Sujiva from the royal family of Kucha. He taught the seven keys of music that can be traced back to India. The Indian goddess of music, Sarasvati was also worshipped in Central Asia. An 8th-9th

century painting of Sarasvati on a wooden penal is discovered from Yarkhoto.

Kucha thus loomed large as a veritable outpost of Indian culture.

The

paintings from Dun-huang showing the legend of Ajatasatru and the meditations

of his Queen Vaidehi on Amitayus picture goddesses playing the reed organ

(sheng), flute, clappers, pipe, five-stringend zither (Chinese chin), cymbals,

reed-pipes, and other instruments. The paintings of the Western Sukhavati

paradise of Amitayus show sixteen musical instruments.

Buddhist sutras for State Protection and Consolidation of the

State

Sutras like Suvarnaprabhasa

played an important role in the polity of East Asia. There are a number of

references when the emperors acting as religious and political leaders used

religious means for political gains. For them recitation of

Suvarnaprabhasa-sutra and the ceremonies based on it, were meant for peace and

prosperity of the country, for its protection from enemies, for the wellbeing

of the public and the rulers, and to save the masses from calamities

The Chu-yung-kuan pass has been one of the

nine important gateways to China at the Great Wall. This gate was constructed

as a protection against barbarians from the north. An Imperial Arch was

constructed in 1333 and a 36 feet long inscription was

inscribed in Sanskrit: Usnisavijaya-dharani, for protection of the capital Beijing. The use of Sanskrit Sutras for National Defence in China goes back to ancient times. When Hsuan-tsang returned to China, the Emperor invited him to stay in the palace. He was delighted to know that the six hundred scrolls the pilgrim had translated contributed to the protection of the State.

Garuda, Mural, Kizil Cave 178, Kucha, Xinjiang, China. Photograph by Benoy K Behl.

Garuda, Mural, Kizil Cave 178, Kucha, Xinjiang, China. Photograph by Benoy K Behl.

Full caption by Benoy K Behl - From Sri Lanka and South-East Asia up to China and Mongolia, one of the favourite representations is that of Garuda, the vahana,

or vehicle, of the deity Vishnu. This powerful eagle remains the national

symbol of Thailand and Indonesia and is one of the popular deities in India.

Rituals and Ceremonies: Sanctification and Divine Empowerment

Fahien, a Chinese pilgrim has stated that an annual car festival was celebrated in Central Asia as a national event, for fourteen days. Each day was allotted to a particular monastery on which the monastery used to take out its images in a procession. Hsuan-tsang says that every five years a religious assembly was held in front of the two colossal images of Buddha outside the capital town for ten days and the event was celebrated as a national festival. Religious festivals were a regular feature in Kucha as well as Khotan.

Dedication ceremonies was a fashion in Classical Central

Asia. It was believed that by offering a banner with dedication the donor or

his relatives would gain admittance to paradise more easily or they would be

blessed with long life, or numerous children or prosperity. The offerings could

also be presented as a thanksgiving for even a successful business trip. Due to

a big demand a variety of offering banners were produced on a large scale in

temple workshops. 8th century banners from Kocho are among the most

beautiful. Similar banners are found from Turfan, Yarkhoto and at Dunhuang

caves in China.

Chanting sutras associated

with Tantric rites, for protection of the nation became a practice during the

Nara period in Japan. Sanskrit mantra, Usnisavijayadharani, written on the

Great Wall of China, for the protection of the capital Beijing runs into 36

feet.

Bowls made for the personal use of the

Chinese Emperors with Sanskrit benediction mantras and bijas are kept at the

museums. An interesting document of Sanskritic heritage in Central Asia is the

so-called Bower manuscript that contains seven medical texts written by four

different persons, all of them were residents of Kuchean monasteries.

Figures on the banners were drawn with stencils. Their use in monastery workshops was unavoidable due to a great demand and strict iconographic requirements. Simple and unpretentious stencil paintings reveal Chinese influence both in slightly modulated brushwork of the ink lines and in full bodied physique of the Bodhisattvas, reflecting T’ang aesthetic ideals.

Author Prof. Dr. Shashibala is Dean, Centre of Indology, Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, New Delhi.

Also

read

1. The Tarim Basin in Xinjiang was Kashmir’s twin - After being converted to Islam, the

descendants of the previously Buddhist Uyghurs in Turfan soon lost memory of

the origins of the caves.

2. The

Rama Story and Sanskrit in ancient Xinjiang

3. The

Saka Lands linking India and Europe

4. Pictures

of Cultural Documentation (has Buddha and Shiva too) in Central Asia

5. Pictures

of Northern Frontiers of Buddhism (has Mongolia, Buryatia in Siberia)