-

Unlike few before it this movie is related to recent events & gives aam aadmi a peep into the corridors of power in Delhi. It explores who Manmohan Singh was - An obstinate Dhritarashtra, family loyalist like Bheeshma or a warrior like Arjuna who did not want to fight. It also has media advice for Prime Ministers.

Much has

been written about The Accidental Prime Minister, from moderately appreciative

commentaries on one side to a seemingly predictable rush of churlish one-star

reviews on the other.

Notwithstanding

these pulpit-protected petty put-downs, it looks like a lot of people are

watching, and enjoying, a movie quite unlike any other made in India until now.

The Accidental Prime Minister is contemporary (the politics, the music,

the persona of the worldly but loyal hero). It is morally engaging (duty,

family, nation). It is grandly civilizational (Bheeshma-Kaurava references, the

cool folk-epic Om song at the end), and most of all it is awesomely media and

21st century in the sense of being “real.” After all, it is based on a

nonfiction book, it features living, real life characters, attempts to reveal

their hopes, flaws and vanities, and most of all, makes viewers think about

what is at stake this year with elections looming ahead. It’s that seriously

grittily sort of real.

The theatre

in Pune where I saw the film recently had around 30-40 people on a late

afternoon show on a working day nearly one week after its release, and they

were certainly engaged with the story. One person in the front rows cheered

appreciatively when Sanjaya Baru, the narrator (and author of the book on which

the movie is based), makes his entrance in the movie. Someone also applauded

Prime Minister Manmohan Singh in moments when he shows spine. And yes, the

cleaning staff at the end were humming the Om song after it all ended (I stayed

till the end credits to enjoy the song, and highly recommend it).

I think the movie affirms something alive and intangible which was perhaps not quite represented in media as it ought to have been until now. It's not so much the knowingness of it all (the thought that we all knew she was running the show really and her cronies were looting us all even as we get surveilled on, tax-formed on, bossed around on, pushed aside in traffic on, and lectured about Hinduism being Evil on constantly). It's more than that. When the book came out in 2014, it affirmed public knowledge with insider authority. Sure. But what this movie has done is something more. It reminds us somehow, in a strange way that is not quite perfect in form (inconsistent sound and occasionally hasty editing) but still earnest enough, that what is alive and tangible and in us still is that word which is supposed to be the zenith of modern idealism itself: democracy.

A Middle Class Duo in the World of the Corrupt and Powerful

The reality show/docudrama conventions are there, sure (the fourth wall stuff is a nice touch as well). But in the end, what cinematic experience can put you inside those elegant Lutyen's offices and drawing rooms that one billion people were all supposed to symbolically/spiritually/democratically all fit inside and have tea with visiting foreign leaders with? We, the people, was on paper. For the middle classes, and for the common man and woman, the experience of this movie is perhaps a little more relatable. It's not a fictionalized take down (or pumping up) of a political leader or party. It is the common man dream of India still; a middle-class professor gets to be Prime Minister, and a middle class journalist gets to be his friend and guide through a new age of image and instant communication at that.

And for me the common man facing powerful enemies moment really came through in the scene of former Prime Minister P.V. Narasimha Rao’s death; a Delhi fixer and villain sneeringly ordering that his body be taken to Hyderabad for cremation with platitudes like “Hyderabad is his janmabhumi.” When Sanjaya Baru’s character retorts about Delhi having been Prime Minister Rao's Karmabhumi, it seemed to me like he spoke every small-town Indian who has lived through the arrogance and snobbery that Delhi durbargiri has spawned for decades in India. If you want to really know why Modi’s India has come to be honestly, remember that moment. It wasn’t primordial religious identity versus secularism but just that.

I think

that what drives the movie, and perhaps its inevitable reference to the 2014

campaign towards the end, is all about that. We the people, they the leaders,

and those two, a little more like us than the leaders ever were, so close, and

yet so far from making it alright.

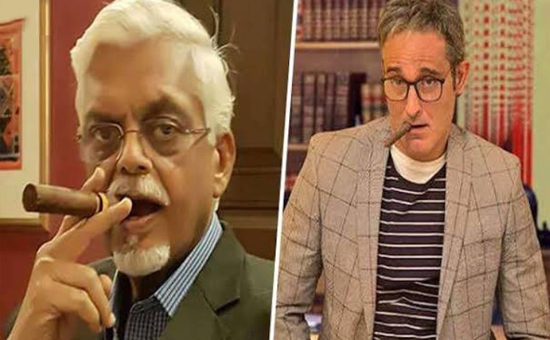

Left

author Sanjaya Baru, right Akshaya Khanna who played Sanjaya role.

Left

author Sanjaya Baru, right Akshaya Khanna who played Sanjaya role.

A Sanjaya Who Saw and Spoke, and a King Who Did Not Listen

Finally,

a bit of a personal insight too into the movie. I must admit that before I

watched the movie I was intrigued about it well beyond its depiction of the

plainer facts of public discourse and democracy and such. I was very curious

about how it would depict one man in particular, for it was based on a book not

only by an author I know, but also was very much about that author I know! It

was one thing when I was younger to watch movies in which my mother acted as

other people, but it was quite another to now see a movie in which an actor

portrays someone I have known since I was a child. I do not know what sort of

research Akshay Khanna did for his role as Sanjaya Baru, but notwithstanding

absence of physical or even behavioral similarities, I thought his persona in

the movie was indeed convincingly expressive. If he pulled this persona out

from just the voice of the author in the book (and of course on cigars I know

he got a tip on the right way to hold it from the source!) then it is an

admirable performance. Some speak truth to power, and some shout. Others still

know how to whisper smoothly over a cognac and a cigar and tick off the

villains just fine too.

But the

real tragedy of this movie though is not the unwillingness of a Sanjaya to

watch and speak the truth, but the consequences to the whole nation ultimately

that ensue because of the deliberate obstinacy of those who will not listen.

Why a man who entrusted a loyal, watchful and masterful associate to help create his image in the media would suddenly shrink from that role and insist that he didn't care about his image being shredded is one of the mysteries of our time and politics. Neither the book nor the movie guess about Dr Singh's intentions (well, in the movie we are told "kamzor hain"), but one lesson is worth drawing here.

Media Advice for (Even Non-Mauna) Prime Ministers

It seems to me that many old-school people, erudite economists like Dr Singh, and selfless karyakartas like some in the now ruling party and its broader base, simply do not fathom the power of media narratives today. When Manmohan Singh fretfully tells his media adviser in the movie that he doesn't care about media image because he only cares about his work, it seems ominously reminiscent of another decent, hard-working, organization which either naively or deludedly seems to believe that decades of malicious propaganda against it won't matter just because their silent work on the ground will win hearts like Swami Vivekananda did in America in 1893 or something.

I emphasize this point of the movie because it is a lesson that those who have entered the idealistic call of public service, and the inevitable game of power, should grasp. There is no difference between 'work' and 'communication' in the media age. Your ability to

communicate beyond your own camp-followers and steer the broader public

narrative is a part of your work too. Whether the masterful successor of

Dr. Singh who is so different from him in his speech and manner will succeed in

triumphing still over the four years of high-price high-poison hate campaign

thrown not just on him but the whole country and 80% of its people for having

believed in him in 2014 remains to be seen.

Anyway.

As the lead characters say in the movie: Que sera sera.

Bheeshma, Dhritarashtra… Or Failed Arjuna?

The movie

ends with a fantastic song that puts rajneeti in

grand Hindu-cosmic perspective, shouting out “Oms” at a whole lot of

things and ideas, as we see images of India’s people intercut with

making-of-the-movie clips (this music video frankly would beat any of the

inanely happy-days sort of bubble-gum Vikas ads the BJP is circulating for its

campaign frankly, it’s just that good!). That one moment somehow elevated the

visual and narrative space of the main movie into a much bigger cosmic, and

popular sense of what is at stake ultimately with politics. Our trappings of

power may be colonial and modern; Prime Ministers, Parliaments,

Extra-Constitutional Prime Ministers lurking behind “Advisory Councils” and the

like. But our vision as a people of who we are is still so much bigger than

this Lutyens government-issue carpets and furniture ambience our rulers mistake

for heavenly mandate. Om is pravachan. Om is barrel of a gun. Om is dollar and

pound. Om is everything.

Only here

we are, humans in the shadow of an unending passion for the divine, humans in a

game of thrones designed by foreigners in their language and in their manner.

Luckily,

we still have our Sanskriti to the extent that we turn to it again and again to understand a world not of our making anymore, and it is not surprising to think of all the epic comparisons going around with this movie. The narrator refers to Dr. Singh as the equivalent of Bheeshma, a grand and good man himself but trapped in the service of the bad guys, the Kaurava family of our time as it were. Critics though have been harsher, and have compared Dr. Singh to Dhritarashtra instead. I have a slightly different take though on how the movie felt to me (and I must qualify that this is perhaps a judgment based not only on the movie but also its reflection of my lifelong familiarity and friendship with one of its principal characters).

To me,

the story seemed more like what happens when a human Krishna, playful and wise,

urges an elderly Arjuna to action against the forces of adharma- and he simply

refuses to pick up his bow. That’s all. No matter how loyal, astute, and

committed to a clear path of action and victory his guide may be, Arjuna

refuses to fight. Why then did he mount the chariot? Why did he not see the

field clearly as his humble charioteer? We will not know. But perhaps the

lesson for us in this is to recognize how we are all both Krishna and Arjuna

with each other in our lives. Sometimes, we see the path for those we love

clearly and show it to them. Sometimes others are our Krishna and do the same

for us. But in both cases, we must act. In

The Accidental Prime Minister, we see a Prime Minister who simply did not do

what his well-wishers thought he might have done still, despite the odds.

Author Vamsee Juluri is a professor of media studies at the

University of San Francisco and the author most recently of Writing Across a

Cracked World: Hindu Representation and the Logic of Narrative.

To

hear song ‘Om Shabd’ from movie

To

buy book ‘The Accidental Prime Minister: The Making and Unmaking of

Manmohan Singh’