-

Does India lack a strategic thinking approach? How

would the lack of strategic culture of a nation become evident? By outcomes.

- Author looks back on certain seminal events in

India’s post-Independence history.

The IAF strike on the Jaish-e-Mohammed training camp at Balakot to

avenge the Pulwama terror attack has altered the narrative on India’s strategic

thinking. In one stroke, India flexed its muscles and struck deep inside

Pakistani territory, leaving behind the habit of turning the other cheek.

However, people still continue to raise doubts about India’s security strategy

as well as its strategic culture.

The doubt about India’s strategic culture or thinking has its genesis in

an article of the early nineties by George K Tanham, a RAND researcher. The

article set the cat among the pigeons by what the author termed, “India’s

relative lack of strategic thinking”.1 The write up was a research paper to

provide guidance to the Government of the United States (US) on its relations

with India.

Tanham discussed India’s lack of strategic thinking based on its

cultural and political heritage.

Where Tanham left off, others took over and continued to question the

ability of the Indian political and strategic elite to articulate an

appropriate security strategy. This was not only restricted to foreign journals

such as Economist and Guardian, but several members of the Indian strategic

community also joined the chorus on India’s lack of a strategic culture.2

The surprising aspect is that Tanham accepted that Indians were

intellectually well-equipped for strategic thinking, but concluded that they

were informal and haphazard about the process.3 For example, Indians had

difficulty in explaining their plans and intentions regarding the induction of

new weapons4 which altered the regional balance, nor did India publish any

White Papers on security issues.

But does any country need to justify its strategy to any one in

particular, especially to a foreigner? Neither Tanham nor others offered

evidence to back their conclusions.

The question that needs to be asked is “How would the lack of strategic culture

or strategic thinking on the part of a nation become evident?”

Should it be judged by whether the nation publishes a white paper on

security strategy on a yearly basis or by the number of ‘think-tanks’ present

or articles published by the security establishment? Outsiders or foreigners

may not understand the decision-making process or the underlying beliefs and

insecurities or they may be biased since the decisions do not conform to their

expectations? One would suggest that the best method of judging the efficacy of

a nation’s strategic culture or thinking would be by the long-term

outcomes on security and foreign policy issues.

Let us briefly assess the outcomes of Indian strategic decision-making

over the decades following independence. Before we do that, let us see what

strategic culture is all about.

Nation states like individuals, display unique identities, personality

traits and behaviour. These are shaped by factors such as geography, heritage,

culture and historical experiences. A nation’s instinctive reaction to crisis

situations is triggered by these factors. These beliefs also consciously or

unconsciously impact foreign policies and security strategies.

This was what led Jack Snyder to coin the term ‘Strategic Culture’ while

analysing the nuclear strategy of the erstwhile Soviet Union.

The Soviet strategy somehow did not follow the American thinking based

on rationality. It was rooted in the insecurities of the Soviet Union’s past

experiences. These differences made it difficult for Americans to predict

Soviet responses.

Snyder defined strategic culture as “the sum total of ideals,

conditional emotional responses and patterns of habitual behaviour that members

of the national strategic community have acquired through instruction or

imitation and share with each other with regard to [nuclear] strategy.”5 If

this is what strategic culture is all about, then it should really be the

foundation of all major strategic decisions.

If one looks back on certain seminal events in India’s post-Independence

history, some assumptions which guided the behaviour or actions of the nation

should emerge, helping us understand if there are some consistent features

which guided Indian policy making.

One belief which emerged early on was based on its colonial experiences

which firmed up its resolve to be the master of its own fate and retain

political and strategic autonomy.

As regards heritage, most Indians are quite conscious and proud of it,

as also of the non-violent struggle for independence. These aspects influenced

its approach of stressing on peaceful resolution of differences.

Added to this was the fact that Hinduism does not believe in proselytisation.

India thus remained a non-aggressive state, quite content to maintain

territorial status quo. Such beliefs quite obviously, resulted in being

reactive and being dubbed as a “soft state”.

However, this did not detract from the fact that India protected its

vital interests and integrity quite resolutely.

Lastly, another belief that has matured over time is that India is a large

country, with a rich culture and heritage and was very prosperous before it was

invaded and colonised. This has resulted in the firm belief on the inevitability of India’s

rise, regaining its glory as a prosperous nation. Many of these beliefs have

consciously or unconsciously guided its foreign policy and security strategies.

These beliefs and emotions are what to a large extent, comprise its Strategic

Culture which would be evident from the discussions that follow.

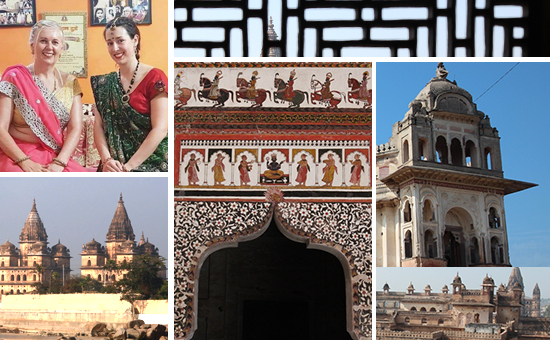

There is more to India than the Taj-West.

There is more to India than the Taj-West.

Moving on, let us look at the first major policy decision that impacted

India’s foreign policy. This was India opting for non-alignment. The term

‘non-alignment’ was coined by V Krishna Menon in his speech at the UN in 1953.

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru’s furthering the concept of non-alignment brought India

a lot of prestige. It was devised to retain the nation’s independence in the

face of a complex international situation demanding allegiance to either

Western capitalism or Soviet communism. Such a decision taken, when India was

dependent on US dole, is indeed surprising and pointed towards its firm belief

in assuring itself autonomy in policy making.

Later, when circumstances required, it signed a friendship treaty with

the Soviet Union and after the end of the Cold War and break-up of the Soviet

Union, abandoned its non-alignment policy if not officially, at least in its

dealings with countries. Its relations with countries today are more on the

basis of convergence of interests and mutual benefit.

Maintaining political autonomy which had driven India’s policy of

non-alignment was extended to the nuclear field as well. It started in the

1960s during the negotiations on Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT).

India’s stand then was that it cannot accept norms thrust on it in matters

which would infringe its sovereignty.6 India demonstrated its nuclear weapons

capability in the 1974 as a peaceful explosion, ironically labelled the

‘Smiling Buddha’. Looking back, this was most likely in response to US

intimidation when its 7th Fleet sailed into the Bay of Bengal during the

Indo-Pak war of 1971.

This worked as an effective hedge in an asymmetric international system

which was attempting to corner India. The response from the powers that be was

quick in setting up the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) to keep a nuclear India

at bay.

The indefinite extension of the NPT in 1995, without any assurance of

disarmament on the part of P5 members, proved India’s earlier posture of not

accepting a discriminatory nuclear world order to be prescient. India’s

attempts for a nuclear test ban from earlier times to contain or roll back the

course of nuclear arming, came to naught with the indefinite extension of the

NPT. It was, therefore, natural for India not to sign the Comprehensive Nuclear

Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) and as India’s ambassador at the conference said, “India

will not sign this unequal treaty, not now, nor later.”7

The attempts to corner India and the regional environment of Chinese

nuclear weapons status and its illicit nuclear nexus with Pakistan, finally

forced India to unveil its weapon status by conducting a series of nuclear

tests in May 1998. India, thereafter, declared a unilateral moratorium on

nuclear testing. Its actions were vindicated in the long term when it entered a

nuclear agreement with the US in 2006, ending its status as a nuclear pariah.

India’s approach towards nuclear energy and weapons was dictated by its

long-term interests of protecting its autonomy despite pressures and to some

extent, coercion from the international community. It did this through skilful

negotiation and hard-headed thinking; quite contrary to what many would have us

believe.

As regards military operations or wars, all militaries have their bad

days. India’s nightmare was the 1962 India-China war and there were other bad

days such as Operation Pawan in Sri Lanka. But it had sunshine times as well,

when the Indian military and the security establishment acquitted itself

commendably.

There is more to India than the Taj-South.

There is more to India than the Taj-South.

One operation, which was a landmark in the post-independence

history, was the sweeping victory in the war with Pakistan in 1971. This was possibly the first comprehensive Indian military victory in a millennium. But somehow it has not received the attention that the victory deserves. The entire war was planned and executed with unmatched élan and grace. Diplomatically, Indira Gandhi out-manoeuvred Pakistan and USA, its main supporter at that time.

Can such an all-encompassing military and diplomatic victory be achieved

without strategic planning and clear thinking? Unlikely to say the least.

Based on the above, it is difficult to understand an off-handed

statement that India has displayed a lack of strategic culture or thinking. The

first and foremost objective of any nation state would be to maintain its

integrity. Many would recollect that immediately after independence and even

till recent times, the favourite pastime of the Western press and

intellectuals8 was the doomsday prediction of India’s balkanisation. India was

not expected to survive as a country for long because of the diversities and

regional imbalances. Like VS Naipaul puts it succinctly in his book; India: A

Million Mutinies Now, “All over India, scores of particularities that had been

frozen by foreign rule, poverty, lack of opportunity or abjectness had begun to

flow again”.9

That India tackled and continues to tackle the many rebellions and

challenges to its integrity and still flourishes as a nation, is evidence

enough that its strategies and thinking did achieve the primary aim of any

nation, which is to maintain its integrity. Many countries have faltered on

this count.

Secondly, the method

of assessing strategic culture or thinking by the volume and extent of written

texts or publications may not be entirely relevant in the Indian

context. This is because India has a highly evolved and a long-standing oral

tradition stretching back thousands of years. The age-old venerable Vedas,

Hinduism’s original texts, have been preserved for centuries without loss of a

single syllable through oral traditions.10

Written texts and notes may be an obsession of the West. In India however,

the practice of the written word is gaining ground now. There may be an additional

reason for the lack of published security policy documents.

When a country is not powerful enough to influence actions of other

parties, publishing policies objectives which may not be achieved or which may

prematurely unveil its strategies, would make little sense. It is then

preferable to avoid explicit declarations on security or foreign policy issues

and play one’s cards as the situation unravels.

This approach to some extent has resulted in India’s policies

being dubbed reactive. The lack of written policies does not in any manner indicate absence

of strategic thinking in India’s case.

Lastly, has the country managed to protect the primary interests of

security and welfare of its citizens? There can be differing views on this

issue depending on one’s political beliefs or comparison with other countries.

But whatever be the yardstick applied, the outcomes have been substantial. They

may not measure up to expectations of many and may at best be dubbed as not

measuring up to India’s assumed potential.

Orchha is a wow heritage town in M.P.

Orchha is a wow heritage town in M.P.

Just as an aside, questions may be raised about Western powers or even

the US, if one judges the efficacy of their strategic culture and thinking by

the outcomes. They have innumerable think tanks and substantial literature on

security and foreign policy issues. However, from Korea to Vietnam, Somalia,

Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Syria and the ISIS, the mess that one observes would

hardly bring credit to any entity that claims to possess a high degree of

strategic clarity and ability to understand second order consequences of

decisions- the known unknowns.

It would thus be in order to accept criticism of India’s strategic

thinking as expected when a supposedly weak or an unassertive power bucks the

system. India’s clarity on its vital interests, understanding of its historical

experiences and awareness of its limitations in terms of national power to

influence events has guided its policies and strategies. It has, however, stood

up to be counted when its interests were at stake.

Indians need to peep into the rear-view mirror and see how India in the

post-Independence years has skilfully negotiated the pot-holed and

obstacle-ridden path and has slowly emerged as a strong nation in its own right.

Endnotes

1. Garretson Peter E, Tanham in Retrospect: 18 Years of Evolution Indian

Strategic Culture, 22 January 2013,

http://southasiajournal.net/tanham-in-retrospect-18-years-of-evolution-in-indian-strategic-culture/

2. Ibid

3. George K Tanham, Indian Strategic Thought: An Interpretative Essay

https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/reports/2007/R4207.pdf

4. Garretson

5. Nayef Al-Rodham, Strategic Culture and Pragmatic National Interest,

6. Conflict and Security, 22 July 2015,

https://www.globalpolicyjournal.com/blog/22/07/2015/strategic-culture-and-pragmatic-national-interest

7. Anand Ratkal, What is the Indian viewpoint on the global nuclear

disarmament issue and the NPT and CTBT in particular?

https://idsa.in/askanexpert/Indianviewpointontheglobalnucleardisarmament

8. Ruhee Nag, CTBT at 20: Why India Won’t Sign the Treaty, 23 September,

2016, https://southasianvoices.org/ctbt-at-20-why-india-wont-sign-the-treaty/

9. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/break-india-says-china-think-tank/articleshow/4884439.cms?utm_source=contentofinterest&utm_medium=text&utm_campaign=cppst

10. Excerpt from: India: A Million Mutinies Now, VS Naipaul,

https://www.penguinrandomhouse.ca/books/203596/india-a-million-mutinies-now-by-vs-naipaul/9780307401717/excerpt

11. Celebrating the Oral Traditions of India, Indian Culture and History, November 2018, http://www.kaleidoscopeofmylife.com/2018/11/20/celebrating-the-oral-traditions-of-india/

Author is a former test pilot and has commanded an Attack Helicopter Sqn. He is a PhD in Defence Studies from Osmnia University.

Article is courtesy Indian Defence Review and was

first published here

eSamskriti.com has obtained permission from IDR to share.

You may like to visit India's largest online military newspaper www.indiandefencereview.com.