- What is Bada Mangal, and why

and how is it celebrated in Lucknow? In this exploration, Akanksha delves into

the intricate web of stories surrounding Bada Mangal, involving the Nawabs of Awadh.

This culturally and historically significant region, now part of Uttar Pradesh,

encompasses historical sites such as Ayodhya, Naimisharanya, Kannauj, and many

others.

4th June 2024. As the election results were confirmed, PM Modi walked into the BJP office in Delhi. Within the first minute of the speech he mentioned that the election results have come on an auspicious day, “Today is Bada Mangal”, The Big Tuesday. To most Indians this uniquely local reference to a Lucknow festival would have drawn a complete blank. What is Bada Mangal? Where, how and why is it celebrated? Here is a dive by Akanksha into the complex web of stories around Bada Mangal from the capital of the state that has been the epicentre of not just the 2024 election surprise, but of political plots since the mid 18th century.

Awadh, the Indo-Gangetic plains of India. The Hindu month of Jyeshtha is the peak of Summers. The

wind turns hot, burning through the skin. The rivers run dry. The Amaltas trees

blossom golden yellow. And Lucknow, the city of Lakshman, transforms into the city of the one who rescued him: sankat mochan,

the one who eradicates all troubles, Shri Hanuman.

The four or five Tuesdays of the lunar month, in almost every street of

Lucknow, there are Bhandaras offering delicious food, cooling sherbets and prasad to

the passersby. Monkeys receive special offerings of jaggery and coriander. In

most temples - small or big - one can hear Hanuman Chalisa, or Sundarkand or

the akhand path of the entire Ramcharitmanas.

This tradition of Bade Mangal (Bade = Big; Mangal = Tuesdays) is

unique to Lucknow, the capital city situated on the banks the river Gomti.

The festival goes back to the end of the 18th century, to the dark

corridors of power, when the English East India Company was firming its base in

the heart of this rich granary of India, twisting and turning the fortunes of

many. Some went down, some came up, only to go down again. Whoever suited the

company, for however long was welcomed into these corridors. How he would exit,

if at all, could never be known.

1. There are many tellings around how the Bade Mangal started.

Here is a story that emerges from the life of one such man, Mirza Manglu.

After 20 years of exile in Banaras, he was returning back to Lucknow to ascend

the masnad (throne) and become the sixth - and in effect, the last -

Nawab of Awadh: Saadat Ali Khan II.

This unexpected turn of events was happening with the shrewd planning of the East India Company; a reluctant nod of his very powerful step-mother, his father’s chief consort, Bahu Begum; and fervent prayers of his own mother, the second wife of Shuja-ud-Daula.

Each of the above - through an intriguingly complex chain of stories

flushed with desire, insecurities, ambitions and greed; blended in with the

political and religious history of Awadh - have contributed to this unique

celebration that still carries on in 21st century Lucknow, some 250 years

since.

2. Stories of Awadh

Awadh, a-wadh, that which is indestructible. This land has witnessed

many kingdoms, come and go. It has witnessed many stories of the desire for

power, rise and fall. In the eternal theatre of its past it has witnessed many

heroes, many villains, emerge and disappear.

The Bade Mangal festival is rooted in the ancient-most history of Awadh - Ramayana, and it emanates from one of the most contemporary chapter of Awadh’s history - the Shia Nawabs of Awadh.

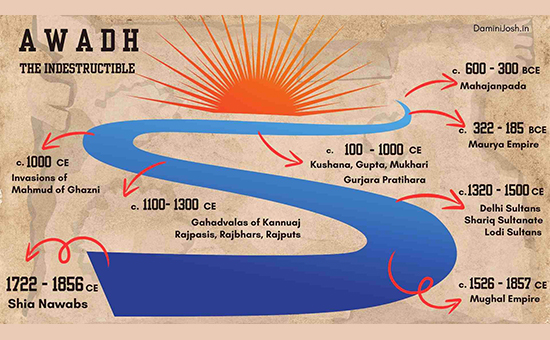

The western historical tradition dates the history of this region from 600

BCE, as a part of the Kosala and then the Magadha Mahajanapada. Through the

centuries the river of power flows, making various kingdoms manifest and

dissolve.

Awadh has seen the centripetal force of power move inwards, concentrate,

like a great whirlpool, making empires arise. With time, the concentrated

energy of power dissipates, becomes centrifugal, the empires dissolve. Then

others arise.

This cycle goes on. Empires, big or small, come and go. Some at harmony

with the ethos of this land whilst others at perpetual war with it.

The Mauryas, Kushanas, Guptas, Mukhari, Gurjara Pratihara, Gahadavalas, Tughlaqs, Shariqs, Lodis. Awadh has witnessed the eternal river of power ebb and flow … on and on.

Sixteenth century sees this river of power concentrate again, leading to

the emergence of the Mughal Empire. By the end of the century Awadh is firmly a

part of the Mughal Empire.

The city of Lucknow is then given as jagir by Akbar to Shaikh Abdul

Rahim, whose descendants, the Shaikhzadas, rule the city. This, till the energy

of power begins its centrifugal movement. In the early 18th century Aurangzeb

dies, Mughal Empire then begins to dissipate.

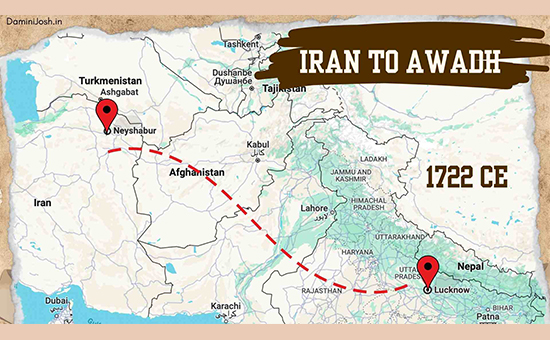

This is when Lucknow begins to emerge as a city rivalling Delhi in culture, opulence and grandeur. In 1722 CE the rule of the Shia Nawabs of Awadh hailing from Nishapur in Iran begins with Saadat Ali Khan I being made the governor of Awadh by Mughal emperor Muhammad Shah ‘Rangile’. No one could

see it back then, but the seeds of the Bade Mangal were sown at this point.

3. Nawabs of Awadh

When Aurangzeb took the reins of the Mughal power in his hands, he banned

the Persian New Year, Navroz, which had been celebrated in the Mughal kingdom

since Babur. It was considered un-Islamic. While Persian remained the official

language in the Mughal courts, it is believed that in a Sunni Delhi ruled by

Aurangzeb not many Persian Shias felt welcome. However, in 1707 CE after

Aurangzeb died many Shias started migrating to India.

Saadat Khan from Nishapur in Iran was one of them. He slowly made his way up the crumbling Mughal court’s hierarchy till he was granted the Governorship of Awadh in 1722 CE. With the entry of the Persians from Nishapur (Neyshābūr), a new chapter unfolded in the history of the Awadh.

Till then, the governors would keep on changing. But now, for almost 135

years one family held on. This happened during that very potent time in India

when one power centre, the Mughal Empire, was crumbling and another power, the British

Raj, was rising.

In the midst of these were the Rohilla Pathans, the Marathas and the Shai

Nawabs- not to forget, the Persian Nadir Shah and the Afghan Ahmad Shah Abdali

- all competing for power in this region.

The festival of Bade Mangal started right in the middle of this turbulent

time of transition in India where wars, plunder, anarchy, conspiracies,

betrayals, and assassinations prevailed. Not just in the barracks and the

bazaar, but also in the bungalows.

4. The 18th century Power Centres of Awadh

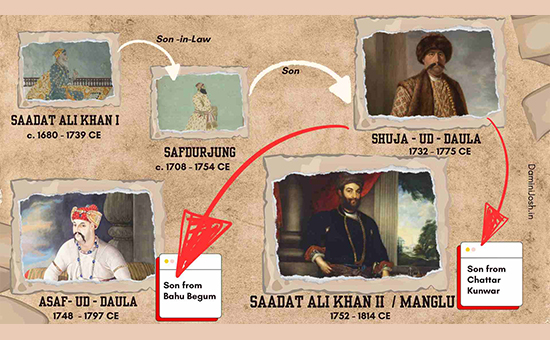

For Saadat Ali Khan I and his successor Safdarjung- the husband of his

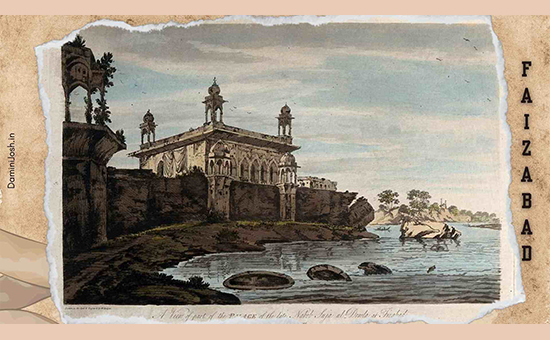

daughter Sadar-un-nisa - the capital was not Lucknow but Faizabad (near Ayodhya), then known simply as “Bangla” after the hutments made there.

It was Sadar-un-nisa and Safdurjung’s only son, Shuja-ud-Daula (born 1731) who laid the foundation of Lucknow as the future capital.

His eldest son, Asaf-ud-Daula (born 1748) the fourth and arguably the most

loved Nawab of Awadh built upon the foundation of Lucknow laid by

Shuja-ud-Daula and shifted his capital there.

His mother, the Khaas Mahal, chief consort of Shuja-ud-Daula, was

instrumental in his ascending the masnad, but their relations deteriorated just after, when he started constantly demanding hefty sums from his mother’s personal treasury.

It is widely believed that it was to run away from the power of the Begums

of Awadh that Asaf-ud-Daula took refuge in Lucknow and declared it the capital

of Awadh. This was, of course, done with the blessings of the new power in the

region, the English East India Company.

5. Shifting the Lens | The Begums of Awadh

For a while, in the late 18th century it looked as if Awadh had two capitals. The Mardana (Men’s quarters) part of it was in Lucknow and the Zenana (Women’s quarters) in Faizabad.

In Lucknow, the new capital, resided the upcoming powers: Nawab

Asaf-ud-Daula, the East India Company resident, and other Europeans. In

Faizabad, the old capital, resided the powerful and rich Begums of Awadh, the

grandmother and the mother of Nawab Asaf-ud-Daula.

Sadar-un-nisa aka Nawab Begum was Saadat Khan’s daughter and Safdurjung’s one and only wife. From her womb was born the lineage of Nawabs of Awadh. She was conscious of it, and she made sure everyone around her remembered that, clearly.

In 1739 Nadir Shah from Persia, all but decimated the crumbling Mughal

empire by ransacking Delhi, killing anywhere between 20,000 to 30,000

civilians.

Saadat Ali Khan I - harbouring an ambition to become the Wazir of the

Mughal Empire - betrayed the Mughal Emperor. Driven by desire for power and

revenge, he was instrumental in opening Delhi to the Persian invaders.

In his seminal work on the First Two

Nawabs of Awadh, historian Ashirbadi Lal Shrivastava explains the events.

Saadat Khan soon got the results of his actions. Within weeks, in Red Fort

itself, Nadir Shah insulted him. Saadat Khan, unable to bear the insult,

consumed poison at night. This was the tragic end of the first Nawab of Awadh.

Saadat Khan’s death led to many former chieftains in Awadh reclaiming their independence. Safdarjung, the new Nawab, felt weak and unwilling to control.

This was the time when the courage and intelligence of Sadat’s daughter shone. It was Sadar-un-nisa who guided and encouraged husband Safdarjung to fight the chieftains and keep Awadh together under the Nawabs. But for her, there may have been no Nawabs of Awadh in the future.

Sadar-un-nisa had the power of her lineage, riches from her dowry and most

of all, intelligence of her own. From then on many occasions, she gave not just

her politically astute advice but also gave financial help from her own

treasury. Safdarjung always remained indebted to her. She was his only Khaas Mahal, chief consort whom he had

married through a formal Nikah.

6. Zenana Politics of Awadh

Bahu Begum, Umat-ul-Zohra, was the first wife of Sadar-un-nisa’s only son, Shuja-ud-Daula. And she was no different. Like her mother-in-law, she was her husband’s sole mankuha wife

that is, married by the contractual nikah.

The daughter of a Persian noble in the Mughal court of Delhi, the Mughal King Mohammad Shah ‘Rangile’ had virtually adopted her as his own daughter. Her gala wedding in Red Fort (1745) and her dowry are legendary.

In the peak of the Mughal Empire, while Dara Shikoh’s wedding expenditure cost 31 lakh rupees, in Bahu Begum’s wedding - when Mughal empire was nowhere near its former power - a whooping 46 lakh rupees were spent.

Bahu Begum walked into Awadh with a hefty dowry that was to save Awadh from

annexation by the East India Company, albeit for a while. Shuja-ud-Daula was

marrying Umat-ul-Zohra for political expediency, this he knew. He also knew his

interests lay in many women. But what he did not anticipate is how Bahu Begum -

an illiterate woman - would change the game.

7. Awadh Sold | Entry COMPANY Sarkar

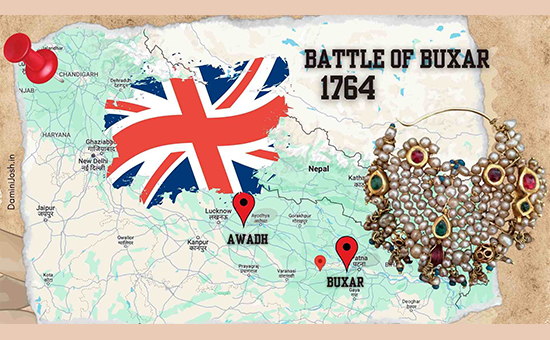

It was actually that one war which

changed the game for the future of not just Awadh, but all of India: Battle of Buxar, 1764. The Mughal forces - including

Awadh - lost, in-fact were humiliated. East India Company got the break they

needed to start making in-roads into the heart of northern India.

By the right of conquest Awadh was now under the company. If Shuja-ud-Daula (1732-1775) wanted the land and his recognition as the hereditary ‘natural prince’, he would have to … yes, buy it. The price was put at 55 lakh rupees, half of this was to be paid in cash within a month.

From its confinement to the east coast in the north, the company’s tentacles had now spread into the heart of northern India. Awadh would now be the mercy of the British, from 1764 till 1947.

For this huge sum Shuja-ud-Daula appealed to all. He promised to repay

anyone who assisted him with double the amount they contributed. Most sent only

a token amount, nowhere close to what they could afford. But Bahu Begum grandly

stepped into her role as his Khaas Mahal, offering all her possessions,

even her nose ring with its bunch of pearls that no married woman would part

with.

In effect, she bought for him and his future lineage the entire empire of

Awadh. A fact she never forgot nor let anyone forget, “… in actuality, it all comes from me,” recollects her munshi, Mohammad Faiz Bakhsh in Tarikh-i

Farah Bakhsh (Memoirs of Delhi & Faizabad Vol II)

Post the Battle of Buxar, a new Anglo-Awadh era was dawning powered by Bahu Begum. This, Shuja-ud-Daula, always remembered. The 18th century Indian historian Ghulam Husain Khan tells us, “Whatever he acquired, he gave the remainder to his wife after expenses.”

Shuja-ud-Daula placed the seals of his government in her custody. He also granted her an additional jagir. She was allowed to enjoy a perquisite derived from “a tax of a twenty-fourth part of the yearly pay of every officer and soldier of cavalry.”

He treated her with great devotion and respect, making sure he has both his meals at her palace. His nights were spent at her palace. This was a big commitment for a man who was known for his promiscuous nature. Chroniclers of the time tell us, if he was not present in her palace at night, he’d pay her 5000 rupees, “stipulated fine for his nocturnal misbehaviour.”

A.F.M Abdul

Ali in his paper on Bahu Begam’s Will

tells us that “Shuja-ud-Daula had so high a regard for her that no one dared utter before her the names of his inferior wives or the names of his other sons except Asaf-ud-Daula, her own-born.”

Bahu Begum would call the palaces of his other wives, “Chor Mahal”, Palace

of Thieves. You see, the other wives of Shuja-ud-Daula were not mankuha, married by contractual Nikah. Although he was legally permitted to marry up to four, he did not. His other wives were mamtu’a wives - “those married by the far less prestigious mut’a or ‘temporary’ rite recognized only by Shi’a jurists.”

One of such wives - khurd, or junior

begums - was Chattar Kunwar the mother of Mirza Manglu a.k.a

Saadat Ali Khan II. Not much is known about her except for the fact that she

was the daughter of a Hindu, a Thakur from Banaras.

Chattar Kunwar – Janab Aaliya - was the first of the mamtu’a wives

of Shuja-ud-Daula. How she was received by Bahu Begum, can only be imagined as

history has all but wiped her name! Whatever remains of her, is the gift of her

prayers for her son, and the lord she revered, mangal murati - the form

of auspiciousness itself - Hanuman.

8. Mirza Manglu: Son of a Junior Begum

Chattar Kunwar lovingly named her first child after the day he was born.

Manglu, the one born on a Mangal, Tuesday, the day of Mangal Murati, Hanuman.

Manglu was the step brother of the fourth Nawab, Asaf-ud-Daula (1748-1797), Bahu Begum’s only son. His childhood was spent in Faizabad. Sometimes when he would come to Bahu begum’s palace to play with Asaf-ud-Daula, his father, Suja-ud-Daula, would make him sit on his lap and tell Bahu Begum to “… give him some love, Begum, someday he will make you proud of him.”

Perhaps destiny heard his father’s words. The way to the masand of Awadh was arduous, but it happened.

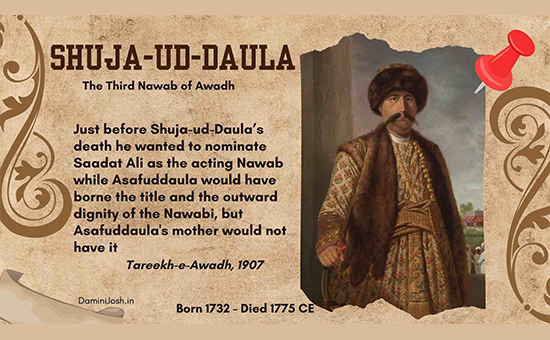

Manglu was Shuja-ud-Daula’s favourite son, but not Bahu Begum’s. Their relationship was strained from the very beginning. Historian Purnendu Basu mentions in his work on Awadh, “Just before Shuja-ud-Daula’s death he had wanted to nominate Sadat Ali as the acting Nawab while Asafuddaula would have borne the title and the outward dignity of the Nawabi, but Asafuddaula's mother would not have it.”

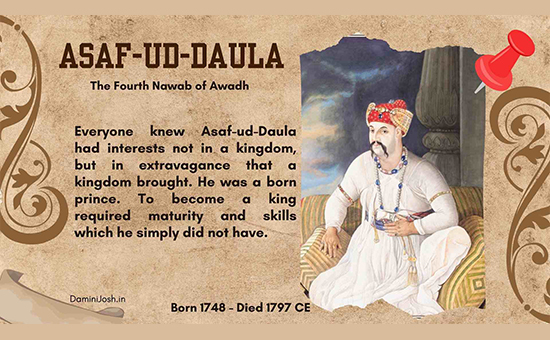

Everyone knew Asaf-ud-Daula had interests not in a kingdom, but in extravagance that a kingdom brought. He was a born prince, to become a king required maturity and skills which he simply did not have. After Shuja-ud-Daula’s death, despite her mother-in-law and

other advisors guiding her against it, Bahu Begum insisted upon her own son,

Asaf-ud-Daula, becoming the Nawab.

The same son slowly ruined all the work her husband had done to put Awadh’s army and administration together; the same son tortured her mother-in-law, her loyal eunuchs, and herself - conniving with Governor General Warren Hastings, making her part with a good amount from the vast treasury she possessed; the same son, destroyed her, bit by bit. But, he was still her son.

9. A Play of DESTINY

Manglu was not her son. But his father trusted him, enough to put him in

charge as the Deputy Minister of Mughal Emperor Shah Alam who had taken refuge

in Allahabad after escaping from Delhi in 1758.

He was then deputed to handle the tough Rohilla Pathans from Afghanistan (Sunni Muslims) now settled in Rohillakhand (includes mainly Bareilly, Moradabad, Polibhit, Shahjahanpur). A task which he handled skilfully. But soon after this he was accused in a conspiracy to overthrow Asaf-ud-Daula. He was pardoned but exiled, albeit with a pension, to Banaras - his mother’s hometown. There he spent nearly 20 years of his life, with many visits to Calcutta, the seat of the British power in north India.

Considered the first ‘westernised’ Nawab, unlike his step brother Asaf-ud-Daula, Saadat Ali Khan II a.k.a Manglu understood the English and knew how to negotiate with them. His banishment from Awadh turned out to be a blessing. Destiny took a turn. Asaf-ud-Daula died at a young age, his successor Wazir Ali, a rebellious spirit was thrown out by the British within four months, and Mirza Manglu found himself ascending the masnad of Awadh.

This came at a cost. He had inherited an empty treasury and an almost

bankrupt state, with reduced income and heavy outstanding liabilities. He would

now have to pay the English an increased subsidy of 76 lakhs a year plus an

additional 12 lakhs immediately to compensate for costs borne by the company to

make him the sixth Nawab.

Manglu was about 50 now. He had waited for long. He knew that for his land,

for his times, this was the best bet. And he was willing to try and make this

work, at all costs.

Historian Purnendu Basu tells us, “He told the ministers, in the presence of the Resident, that he would not require a single rupee from the public treasury for his personal expenses, and to this voluntary promise he adhered strictly. He had already paid out about 20 lakh to the Company from his private treasury. At that time he had only 11 lakh left.”

All this while his mother, Chattar Kunwar - in the shadow of her husband’s chief consort, Bahu Begum - silently witnessed destiny take its roller coaster ride. She emerges from the shadows of history for a brief moment, as her son ascends the masnad. Unlike the other Begums, her emergence is not with

power, wealth or lineage but with prayers.

10. Bade Mangal : Divinty, Dreams and Death

About that night in Awadh historian Yogesh Praveen tells us. Her son, Manglu or Nawab Saadat Ali Khan II - the sixth Nawab of Awadh fell very sick. His whole body was burning. Chattar Kunwar was gripped with fear. What if this turn of destiny was actually her son’s end? No. No. It couldn’t be. She started praying to the Isht of Awadh, Lord Hanuman.

In the middle of the night she woke up sweating, trembling. She could still see around her a diffused white light. Her spine was still shaking. It couldn't be called a khaab, a dream. No. It was a vision. In the divine vision she was being commanded to build a temple for Lord Hanuman. She didn't know how. But she knew this much, it would happen.

In the vision she was shown a place where an idol of Lord Hanuman was

buried. She searched, searched, searched. Some thought her loopy. Some said she

was touched by the divine. But Chattar Kunwar was true to her calling. Her

belief, in the spirit-real, remained unshaken.

Then one day ... There he was. Innocent as a child. Buried under the earth.

Centuries of dust. Washed away by faith. Chattar

Kunwar had found her Hanuman.

An elephant was ordered to carry Hanuman ji to his abode. He walked,

walked. And then, the elephant stopped. Just sat down, refusing to budge. One

would think: get the elephant to move, workers are waiting, so much needs to be

done ... Not Chattar Kunwar. She was a devotee. She belonged to a land that

respected Life. And she knew, God could speak through anything, anyone even an elephant.

His wish was her command. The elephant decided where Hanuman ji would have

his temple. All followed.

The area where the elephant had decided to stop was a locality established

by Bahu Begam in the name of Hazrat Ali, Aliganj. So, it was that in Aliganj

what was to become the birth place of Bade Mangal started being constructed. The birth of the Bade Mangal takes place in the most

tumultuous of the times in the capital city of Awadh.

11. Power, Shifts

Saadat Ali Khan II had been placed in the seat of power with the authority of Bahu Begum. Posted throughout Lucknow was Persian-language proclamation of the Company declaring that the Company had installed Saadat Ali Khan ‘ba-taqrir-i

begam sahiba’, according to the Begum. And now, after it was all done, Bahu Begum was witnessing her own power diminishing.

First, Bahu Begum’s nephew’s jagir was confiscated. Then, her daily ration allowance was decreased from Rs 400 to Rs 200. And most importantly, Saadat was slowly giving his own mother - a lowly Khurd begum - all the rights and privileges which Khaas Mahal Bahu Begum once had sole rights over.

Unlike Bahu Begum’s son who created Lucknow as an alternate centre of power to escape from his mother in Faizabad, Chattar Kunwar’s son was making sure that she stayed with him right there in the seat of power, Lucknow.

Bahu Begum, blinded by hate, did not see. In an Awadh ruined by the extravagance of her own son, where everyone associated being a “Nawab” with being lazy and indulgent, Sadat was courageously carving for himself a reputation of being a “miser”.

Saadat was under tremendous pressure from the Governor General to clear the

arrears due to the Company. He was working at clearing dues, making a reserve

treasury; in a culture of opulence, he was practising economy.

By November 1799 the amount due to the company had fallen into just two

months arrears. But Wellesley again wrote to the Sadat pressurising him to

clear the remainder.

Saadat paid again, a total sum of about 35 lakh. No one knows from where.

No dues remained. But then, pressure started mounting again, this time to

disband the native army. And now their bills had to be cleared, amicably. The

pressure went on and on.

But Bahu Begum was in rage. She could not see this struggle of Saadat to

keep Awadh as her husband, his father had left it. The threat of its cessation

to the company in full or in part loomed large. She was in possession of crores,

a part of it given by Shuja-ud-Daula from the revenues collected from the

people of Awadh, which made her the wealthiest woman in the entire region. She

had lived her prime. If she wanted, perhaps she could have saved Awadh from the

company.

But, over eons, Awadh had seen this pattern. Not far from Bahu Begum’s palace in Faizabad, there was Ayodhya. There lived a queen once.

Just like her, powerful. Just like her, hungry. She wanted power for

herself via her son. For that, blinded by rage, she exiled her stepson. Awadh

remembers Kaikeyi. Awadh also remembers that Kaikeyi was not just a person, she was desire.

A desire that is eternal, sanatan. A desire that can possess anyone, anytime.

Awadh, remembers it all.

In 1799 Bahu Begum expressed her intention to leave her wealth “… to the Company”. There is no way she wanted her step son to even touch her wealth. She was willing to pay any price for that. That meant, speaking directly to the English resident, an unheard of event in the traditional context.

Two power centres were at play again in Awadh, this time both in Lucknow. The Resident and the Nawab. And after Bahu Begum’s decision, everyone knew who would eventually win.

The company stepped in by controlling the finances of Awadh. Slowly, Awadh’s internal politics was taken over - they became the king makers. Then, defence was taken over. Next was foreign affairs. Every message from the nawab would go via the Company Resident.

Eventually, what had to happen, happened. The Company took over a part of Awadh’s land. This would be now directly under the Company. The gross revenue from these was Rs 1.35 crores as against the remainder area of Awadh under the Nawab which yielded 1 crore. The excuse for this action was the non payment by the Nawab of just one month’s arrears.

Awadh’s native army was almost entirely disbanded, only a few troops were left. Now the brave and courageous men of Awadh worked for the company. The East India Company’s Bengal Infantry mostly had Brahmins, Rajputs and Muslims from Awadh as soldiers.

Yet, despite all this, amidst all this, the construction of the temple of

Lord Hanuman in Aliganj continued, as did prayers to him. Saadat Ali Khan urf

Mirza Manglu got two cannons placed in the famous temple of Hanumangarhi in

Ayodhya. He also started the Ramleela of Lucknow during Dusshera.

Saadat Ali was not young, it wasn’t easy, but he was not willing to give up. Whatever part of Awadh that was left under him, he was willing to make a genuine change in it.

Kamaluddin writes in Tareekh-e-Avadh that Saadat had many spies who informed him about what was happening in the provinces. Revenue ministers were limited to overseeing districts of up to 4 or 5 lakh rupees to prevent them from becoming too strong. They were closely monitored and couldn't mistreat peasants. Amils had to promise to maintain good cultivation and revenue levels at settlement. If they failed without reason, they were imprisoned. He didn't give much power to his officers and was accessible to the common people.

12. In Peak Heat, the FLOWERING

Then one day, as the eternal river of power flowed on, the doors to the

Hanuman temple in Aliganj, opened. On the dome of the temple was

placed a star and the crescent moon. People were ushered in,

festivities began. At the centre of the festivities was the sharing of grace in

the form of food, the bhandaras. This

celebration caught on and spread to all parts of the city.

This happened during Jyeshtha, the peak of summers, with the Amaltas trees blossoming golden yellow. And rightly so, for this contrast was what Nawab Saadat Ali Khan, urf, Mirza Manglu’s life was.

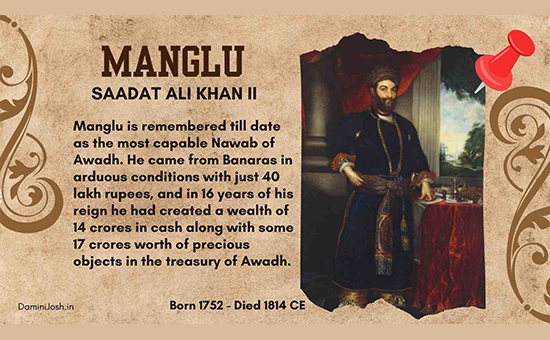

Mirza Manglu is remembered till date as the most capable Nawab of Awadh. He came from Banaras in arduous conditions with just 40 lakh rupees, and

in 16 years of his reign he had created a wealth of 14 crores in cash along

with some 17 crores worth of precious objects in the treasury of Awadh.

But he knew. He had come to power with the cunning of the East India Company. He knew that the rug could be pulled out from under him, anytime. And it was. He was poisoned by his own brother-in-law. It is widely believed this was at the behest of the East India Company’s Resident, Major John Baillie.

A few months after his death, the new Nawab Ghazi-ud-din Haider wrote, “In the day of my late Father's decease, neither the Resident nor anyone of the English Gentlemen attended the Funeral. It is a matter of regret, that the Resident should not have gone in person, nor to have sent any of the English Gentlemen to attend the Funeral of so great a Wazir and so old a Friend of the British.”

Historian Abdul Halim Sharar, in Guzishta Lucknow, gives us an intriguing insight into the times. Saadat Ali was apparently in correspondence with the British Government in England. He was trying that “… the British Government of India should be transferred on contract from the East India Company into his hands. This agreement was about to be finalised when (he was poisoned)”

Strangely, that too was on Mangal, a Tuesday.

Manglu was poisoned on 11 July 1814 CE, he was 62. Bahu Begum out-lived her

stepson by a year. In 1815 CE she breathed her last in Faizabad at the age of

88. When exactly Chattar Kunwar passed away is unclear, but what she left

behind clearly is a tradition that will carry on for hundreds, if not thousands

of years.

The Bade Mangal festival is the nectar born from the churning of 18th century Awadh. A queen’s divine dream became a reality, year after year. In the peak of summers, when the wind burns through the skin and rivers run dry. But the Amaltas blossoms golden yellow!

Author Akanksha Damini Joshi is

an award winning documentary filmmaker, cinematographer, writer, speaker and a

meditation facilitator. Digital Image Art is by her. She can be followed on Instagram @DaminiJosh

To read all

articles by author

Also read

1. About Awadhi

Language

2. Two Brave

Begums of Awadh

3. Best Places

to shop in Lucknow

4. Experience of

Ayodhya Ram Mandir Pran Pratishtha

Editor’s Notes - What is area covered by Awadh

and brief history?

Awadh includes Nimisharanya, Kannuaj (117 kms from Lucknow), Ayodhya

and Faisabad (150 kms from Lucknow). Later it included Varanasi and Jaunpur.

Sri Ram ruled from Ayodhya.

Tulsidas’s Ramcharitmanas, which tells the story of Lord Rama, was written in Awadhi, the local dialect. The region

was a part of Kosala, then the Magadha Mahajanapada and in the 16th

century became a part of the Mughal Empire.

With

the decline of the Mughal Empire on death of Aurangzeb, in 1722 CE the rule of the Shia Nawabs of Awadh

hailing from Nishapur in Iran began with Saadat Ali Khan I being

made the governor of Awadh by the Mughal emperor. It was he who gave Faizabad

(military capital) its name. The town is only 7 kms from Ayodhya.

The

most capable Nawab was Manglu or Sadat Ali Khan II (mother was Chattar Kunwar

of Kashi) who died in 1814. The capital of Oudh was Faizabad but the seat of

the British Resident was Lucknow (Lakhsmanpur-gifted

by Sri Ram to his brother Lakshman post return from Sri Lanka). It was annexed as Oudh in 1856. In 1877,

Oudh was merged with Agra to form the United Provinces of Agra and Oudh.

Post-independence it became Uttar Pradesh. Source

Close to Nagapattinam in Tamil Nadu at Tirumaraikaadu was this Hanuman ji Murti.

Close to Nagapattinam in Tamil Nadu at Tirumaraikaadu was this Hanuman ji Murti.