- Know about the humble beginnings and the evolution of the Ramakrishna Mission, within India and U.S.A, from 1886 till about 1902.

Nineteenth century India was marked by two currents-the challenge of the West and the response of renascent India to it. The former manifested itself in the influx of Western ideas and institutions which followed the establishment of the British paramountcy, and the latter expressed itself through socio-religious reform movements. These movements attempted to rejuvenate Indian society by highlighting the glory of its past and establishing the modernity of its tradition, rationalising religion and social institutions, and by exhorting Indians to inculcate faith in themselves instead of being schizophrenic in aping the West. All the reformist currents of the 19th century—revivalist and non-revivalist, rationalist and militant, orthodox and heterodox, conservative and esoteric—amalgamated in Swami Vivekananda (1863–1902).1

He

laid the foundation of the Ramakrishna Mission in the name of his Master who

epitomised the ideals of renunciation and service. In course of time, the

Mission has grown into a mighty organisation with worldwide centres that remain

engaged in spiritual, social, educational, and ameliorative activities. It is

non-sectarian and non-political, and rejects proselytism. True religion, after

all, lies in self-realisation, in being and becoming, as taught by Swami

Vivekananda.

I: Embryonic Stage

Did Sri Ramakrishna (1836–86) have the idea of an organisation in mind when he was alive? Though he did not directly hint at it, he trained his disciples for monastic life so that they could work out their own salvation and serve humanity at the same time. During the last phase of his life, he commissioned Narendranath (pre-monastic name of Swami Vivekananda) to look after the young devotees. ‘I leave them to your care. See that they practice spiritual exercises and do not return home.’2

Swami

Vivekananda said later that the Cossipore Garden House, Kolkata, where Sri

Ramakrishna stayed for the last few months of his life and took mahasamadhi on 16 August 1886, was ‘the first Math’.3 The Saint

of Dakshineswar gave ochre clothes and rosaries to his chosen disciples, who

later took the vow of renunciation on the night of 24 December 1886 at Antpur

which was followed by performing the Viraja

Homa at a later date, a

fire-sacrifice essential for monastic initiation.

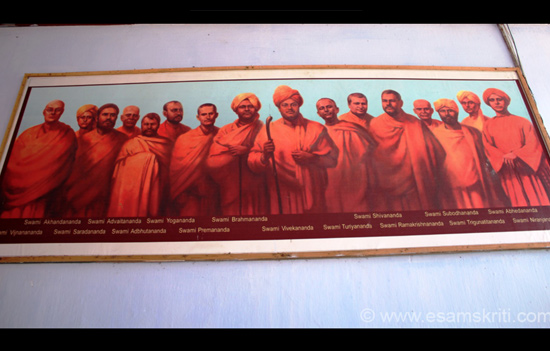

Pics of disciples at RKM School, Deomali Arunachal Pradesh. 2013.

Pics of disciples at RKM School, Deomali Arunachal Pradesh. 2013.

The

nine disciples who were present at Antpur were Narendranath Dutta (Swami

Vivekananda), Baburam Ghosh (Swami Premananda), Sarat Chandra Chakravarty

(Swami Saradananda), Sashibhushan Chakravarty (Swami Ramakrishnananda),

Taraknath Ghoshal (Swami Shivananda), Kaliprasad Chandra (Swami Abhedananda),

Nityaniranjan Ghosh (Swami Niranjananda), Gangadhar Ghatak (Swami

Akhandananda), and Sarada Prasanna Mitra (Swami Trigunatitananda).

Start-up Stage: Baranagar Math (1886–92)

The

Cossipore establishment was closed after the Mahasamadhi of Sri Ramakrishna, as

the lease of the house in which he and his disciples stayed, expired on 3

August 1886, and was not renewed due to lack of financial support, and the

opposition of some older devotees.4

Although there were suggestions that the young disciples should return to

home-life, and build a career for themselves, an informal organisation (sangha) led by Narendranath was formed at Baranagar (Barahnagore), a northern suburb of Calcutta (now renamed Kolkata), on the eastern bank of the Hooghly river (also called Bhagirathi-Hooghly), on 19 October 1886. It is believed that ‘the Master himself helped it materialise’.5

The Garden house, Baranagar, was owned by a landlord family of Taki (North 24 Parganas district), and was hired with the efforts of a devotee, Bhavanath Chattopadhyay, at a paltry monthly rent of Rs. 10. It was in a deplorable condition, and associated with ghostly or supernatural events. But it was soon turned into a place for the highest asceticism. Gopal Junior, whom Sri Ramakrishna called Hatko (one who comes suddenly and disappears quickly), was the first to occupy it. He sanctified the house by bringing the personal belongings of Sri Ramakrishna, like his bedclothes, furniture, utensils, and the like. Much later, the holy relics of the Master were brought from Balaram’s house and placed in the infant monastery to be worshipped regularly.

Tarak (Swami Shivananda, 1854–1934), and Gopal Senior (Swami Advaitananda, 1828–1909), were ‘the first regular inmates’. They were followed by Kali (Swami Abhedananda, 1866–1939), Sashibhushan Chakravarti (Swami Ramakrishnananda,1863–1911), Sarat Chandra Chakravarty (Swami Saradananda 1865–1927), Rakhal (Swami Brahmananda, 1863–1922), Nityaniranjan Ghosh (Swami Niranjanananda, died 1904), Baburam (Swami Premananda,1861–1918), and Sarada Prasanna Mitra (Swami Trigunatitananda, 1865–1914). Some of them stayed permanently as they had left their homes (like Gopal Junior and Gopal Senior), while others, visited it every now and then.6 Mahendranath Gupta (1854–1932), author of the Bengali classic, Sri Sri Ramakrishna Kathamrita

(5 Vols) came occasionally and sometimes stayed for weeks. Narendranath made

the Baranagar Math his permanent abode in the middle of June 1887.

In his ‘Conversations and dialogues’, Swami Vivekananda narrates that they would get up in ambrosial hours and remain absorbed in japa and meditation, sometimes from morning till evening. The monks survived on alms. There were days ‘when the Math was without a grain of food. … Boiled Bimba (Ivy gourd) leaves, rice, and salt—this was the menu for a month at a stretch.’ Many a time, Swamiji thought of ‘abolishing the Math altogether’ but changed his mind due to the strong will and financial

support of Suresh Babu (Surendra Nath Mitra, 1850–90) in adverse situations. ‘He was, in a way, the founder of this Math.’7 Balaram Bose (1842–90), a householder disciple of Sri Ramakrishna, also supported the young monks as long as he lived.

Towards Stability: Alambazar Math (1892–98)

Due

to the dilapidated structure of the Baranagar monastery, the monks moved to a

new and spacious building (spread on an area measuring 22 bighas and 22 sq. ft. or 29433.7269 sq. metres) at Alambazar in February 1892. Among the notable monks who graced it at different periods of time, were Swami Brahmananda (Rakhal Chandra Ghosh, (1863–1922), Swami Saradananda (Sarat Chandra Chakravarty, (1865–1927), Swami Yogananda (Yogindranath Roy Chowdhury, (1861–99), Swami Turiyananda (Harinath Chattopadhyay, (1863–1922) and Swami Vijnanananda (Hariprasanna Chattopadhyaya (1868–1938)

Since the Alambazar Math was an ideal place for spiritual practices, many devotees visited it including, Nag Mahasaya (Durga Charan Nag, 1846–99, a practitioner of homoeopathy and householder-disciple of Sri Ramakrishna), Girish Chandra Ghosh (1844–1912, a famous playwright), Gopaler Ma (Aghoremani Devi, 1822–1906) and Gauri Ma (Mridani, 1857–1938). The last two were the companions of Holy Mother Sarada Devi (1853–1920), the spiritual consort of Sri Ramakrishna.

Swamiji stayed at the Alambazar monastery after his first visit to the West. While in America, he corresponded with his brother-disciples, guiding them on a number of organisational issues. In a letter to Rakhal (Swami Brahmananda), dated 20 May 1897, he wrote: ‘I am glad to learn that the Association in Calcutta is going on nicely.’8 After

returning from the West, Swamiji stayed here for about a year, held religious

classes, initiated devotees, and framed rules for the Math.

Vivekananda Cultural Centre Chennai. On Marina Beach road. Swamiji stayed here.

Vivekananda Cultural Centre Chennai. On Marina Beach road. Swamiji stayed here.

II: Struggle and Flowering-Ramakrishna Movement across

Indian shores

The

idea of forming a spiritual organisation was surely in the mind of Swamiji when

he was a wandering monk in India. It has been argued that one of the reasons

why Swamiji went abroad was to fulfil the mission of his spiritual master.9 At the World Parliament of Religions,

Chicago 1893, he ruefully noted that he came to America to seek aid for his

impoverished people but he found it an uphill task.10

Towards the end of September 1893, Swamiji realised that lecturing was ‘a profitable occupation’ in America, and it could help him in his future projects. Referring to his earnings in Chicago after the close of the Parliament, he wrote to Mrs [Kate?] Tannatt Woods: ‘It is ranging from 30 to 80 dollars a lecture, and just now I have been so well advertised in Chicago gratis by the Parliament of Religions that it is not advisable to give up this field now.’11

Before September 1894, Swamiji had collected about nine thousand rupees in the Indian currency which, as he wrote to Alasinga Perumal on 31 August 1894: ‘I will send over to you for the organisation.’ Swamiji wanted him to start a Society and a Journal and build up a temple in Madras which should have a library and some rooms for the office.12

From his letters, one can see that he was sending money to his disciples for organised social work. He wrote to Swami Saradananda on 20 May 1894: ‘If you all like, you can give to Gopal Rs. 300/- from the amount I sent for the Math. I have no more to send now. I have to look after Madras now.’13 Miss Sarah Ellen Waldo (called Haridasi), a staunch follower of Swami Vivekananda, confirms that he stayed in America to raise funds for his countrymen, ‘to send help to fellow sannyasins in India’.14

It may, however, be stated that the larger aim of Swamiji was to spread the message of Vedanta globally. He intended ‘to create a new order of humanity’ who were sincere believers in God and did not care for the world. He was not satisfied merely ‘with newspaper blazoning’. In a letter to Alasinga dated 14 May 1895, he wrote that he ought to be able to leave a permanent mark behind him. He was hopeful that he would succeed with the blessings of the Almighty.15

At times, Swamiji felt that some people were trying to damage his cause by spreading false rumours about him. But he assured Kidi (Singaravelu Mudaliar) in his letter dated 22 June 1895, that his mission would succeed. ‘I am not (given) to failures, and here I have planted a seed, and it is going to become a tree, and it must. Only I am afraid it will hurt its growth if I give it up too soon. … Rome was not built in a day.’16

By mid-1895 Swami Vivekananda had consolidated his work with the help of some influential and dynamic followers. In a letter to the Maharaja of Khetri dated 9 July 1895, he wrote: ‘I shall make several sannyasins and then I go to India, leaving the work to them.’17

Vedanta Society, Hollywood, Los Angeles.

Vedanta Society, Hollywood, Los Angeles.

Vedanta Society, New York

The Vedanta Society, New York, was established in November 1894 to manage Swami Vivekananda’s affairs, arrange his lectures and classes, and print pamphlets or books for distribution. Although the Society had office bearers, it did not enrol members until 1900. Swami Saradananda and Swami Abhedananda, who had joined Swamiji in England at his instance in 1896, moved to America—the former in June 1896, to take charge of the Society in his brother disciple’s absence, and the

latter in 1897, after finishing his lecture engagements. Together, they got the

Vedanta Society registered in 1898. Gradually, the Society gained strength and

spearheaded the growth of the Ramakrishna Movement.

Collage of pictures Shanti Ashrama, California. April 2015.

Collage of pictures Shanti Ashrama, California. April 2015.

The Proliferation of Vedanta Centres

Swami Turiyananda accompanied

Swami Vivekananda during his second visit to the West in 1899. He made a mark in

the New York centre while Swami

Vivekananda was away in Southern California. He delivered lectures and held

classes in Raja Yoga at Montclair, Cambridge, and San Francisco. The Retreat,

famous as Shanti Ashrama, in

the San Antone Valley, 18 miles south-east of Mt. Hamilton, California, which

had been donated to Swamiji by Miss Minnie C Boock, was used by Turiyananda to

provide a dozen Americans with the taste of true monastic life. However, being

exhausted by strenuous work, he had to return to India in June 1901.

To see Shanti Ashrama

Album

Subsequently, Swami Trigunatitananda

came to San Francisco and broadened his area of activity to Los Angeles. He was

instrumental in procuring a plot of land for the Vedanta Society there. The

building started coming

up in 1905 and was ‘dedicated to the

cause of humanity’ on 7 January 1906. Swami Trigunatitananda

also established a monastery and a convent, and frequently took his disciples

to Shanti Ashrama to

give them practical lessons in the

art of meditation. Unfortunately,

he became

the victim of a bomb attack in December

1914 and left his mortal coil in January 1915.

Apart from New York, Los Angeles, and

San Francisco, Vedanta

centres came up in Pittsburgh (under Swami Abhedananda who was holding the fort

in New York), followed by Swami Bodhananda, and in Oakland and Alameda, with

the support of one Mr C F Peterson. Swami Abhedananda made a great impression

in New York with his winsome personality, intellectual powers, and oratorical

skill. The series of ninety lectures he delivered in the Mott Memorial Hall,

New York, established him as a great exponent of Vedanta, and brought him into

contact with such renowned persons as Prof. William James, Prof. Lanman, and

Dr. Janes, the Chairman of Cambridge Philosophical Conference.

Apart from making frequent trips to

Europe, he lectured extensively in almost all important cities of America,

Mexico, and Alaska, and impressed even Max Muller and Paul Deussen during his

first visit to England (1896–97). He moved to a hermitage of 370 acres at West Cornwall, Connecticut, in the foothills of the Berkshires in 1912, and remained there for about nine years before returning to India where he died on 8 September 1939.

Among other monks of the Ramakrishna

Order who went to America in the early stages of the growth of Vedanta

Societies, were Swami Sacchidananda, who arrived in Los Angeles in 1904, Swami

Nirmalananda, who remained in New York from 1903 to 1906, and Swami

Prakashananda, who joined the San Francisco Centre in 1906. Swami Paramananda

established a Vedanta Centre each in Boston and Washington in 1909; and during

his sojourn in Europe a few years later, one in Geneva.

In the years to come, Vedanta societies were formed in Portland (Oregon) in 1925, Providence (Rhode Island) in 1928, Chicago (Illinois), and Hollywood (California) in 1930, New York City (Ramakrishna-Vivekananda Center) in 1933, Seattle (Washington), in St. Louis (Missouri) in 1938, Berkeley (California) in 1933, Boston (Massachusetts) in 1941, and Sacramento (California) in 1949, followed by many more. The chapters of the Mission were also started in countries other than America—in Argentina, Bangladesh, England, Fiji, France, Japan, Mauritius,

Singapore, Sri Lanka, Switzerland, Russia, Netherlands, and Canada (established

after 1985). The names of Swamis like Prabhavananda, Raghavananda, Dayananda,

Madhavananda, Nikhilananda, Ashokananda, Jnaneshwarananda, Ghanananda,

Vividishananda, Vishwananda, and Vijayananda may specifically be mentioned for

spreading the message of Ramakrishna-Vivekananda

across the Indian shores. 18

III: Compact Organisation and Fruition—Ramakrishna Mission Association, 1897

Shortly, after his return from the West, Swami Vivekananda held a meeting of his brother-monks and the householder disciples of Sri Ramakrishna at Balaram Babu’s residence in Kolkata on 1st May 1897. He declared that nothing fruitful could be achieved without an organisation, and hence proposed the formation of an Association (sangha) in the name of Sri Ramakrishna.

The proposal was welcomed by all, and a few resolutions were passed to

concretise it.

In a subsequent meeting on 5 May 1897, the aims and objects of the Association were delineated. These were, among others, to live and preach the truths cherished by Sri Ramakrishna; to create fellowship among different faiths, which were ‘so many forms of one underlying Eternal Religion’; to carry on missionary and philanthropic work; to ‘promote and encourage’ arts and industries, conducive to the welfare of people; to preach the Vedanta and religious ideas; to establish Maths and Ashramas all over India, and to send trained sannyasins abroad.

Swamiji was to be the General President of the new Order. Swami Brahmananda and Swami Yogananda were to serve as President and Vice President respectively of the Calcutta Centre. To fulfil the objectives of the organisation, regular meetings of the core committee were held at Balaram Babu’s residence every Sunday afternoon. The first General meeting was organised on 9 May 1897.19

From Nilambar Mukherjee’s Garden House (1898–99) to Belur Math

The Assam earthquake (1897), having a magnitude of 8.2–8.3 on the Richter scale, extended into Calcutta (now Kolkata), and caused severe damage to the Alambazar Math building. As a result, the venue of the Math was shifted to Nilambar Mukherjee’s Garden House at Belur on 3 February 1898. The Garden House is now a part of the present Belur Math, and is called ‘Old Math’. The Holy Mother Sri Sarada Devi, the spiritual consort of Sri Ramakrishna, graced it many times with her stay. On 25 March 1898, Swamiji initiated Margaret E Noble (1867–1911) into the vow of Brahmacharya, and gave her a new name ‘Nivedita’, meaning ‘dedicated to God’. He wrote an arati (devotional lyric), ‘Khaṇḍana bhava

bandhana’, and a hymn to Sri Ramakrishna, Om hrīm ṛtam, that are

recited during the evening prayer in all Ramakrishna Mission centres today.

Anagarika Dharmapala (1864–1933), who represented Theravada Buddhism at the World Parliament of Religions, 1893, in Chicago, visited Swami Vivekananda at this garden-house. It was here again that Swamiji revised the Rules of the Math framed at Alambazar and created ‘the comprehensive, final and the ultimate divine constitution’, comprising 116 rules.

In April 1898, the central Math of the

Order began to be constructed in Belur across the river Ganga, about 6 kms

north of the Howrah railway station. It was occupied by the monks on 2 January

1899. Till

his passing on 4 July 1902, Swamiji presided over the Order even after he had

formally transferred the Math property to the Trustees (comprising his 11

brother disciples) by a Deed of Trust, on 30 January 1901. Soon after, the Math authorities

took upon themselves the work of the Mission Association.20

Due to the phenomenal growth of the Math

activities, another society, named the Ramakrishna

Mission, was registered in 1909, under Act XXI of 1860. The two are one

and yet separate legal entities. The ideology of both organisations has a Vedantic praxis to it: ‘Ātmano mokśārtham jagat hitāya ca; for one’s own salvation and for the welfare of the world.’ Both the Math and the Mission lay stress on charitable and philanthropic activities. But while the former lays more emphasis on the Universal Religion, spiritual preaching and training, the key domain of the latter is social welfare of various kinds.

While laying the foundation of the building to house the International Cultural Centre of the Ramakrishna Mission at Colombo on 17 June 1959, Dr Rajendra Prasad (1884–1963), the first President of India, observed:

“The spirit of dedication which is the chief characteristic of every worker of the Mission, is, to my mind, its biggest asset. … Apart from rendering service to those who need it, such organisations do a lot, though silently and imperceptibly, to bring men and nations closer. Their ideal of humanitarian service serves to emphasise the basic unity of human society. The importance of such work cannot be overemphasised, particularly in modern times, when tension threatens to become a part of human nature and a feature of international relationships. Therefore, the least that one can do is to encourage such organisations and to wish them well.”21

Author Dr

Satish K Kapoor is an

Ex-British Council Scholar and ex-Registrar of DAV University Jalandhar, author

and spiritualist.

References

1. Dr Satish K Kapoor, Cultural Contact and Fusion: Swami Vivekananda in the West (1893–96) (Jalandhar : ABS Publications, 1987), vi.

2. Life

of Sri Ramakrishna (Calcutta: Advaita Ashrama, 1955), 582.

3. Prabudha Bharata (January 1998), 79. For Sri Ramakrishna’s last days at Cossipur Garden, see Life of Sri

Ramakrishna, 571–95. The Cossipore Garden-house was turned into a branch centre of the Ramakrishna Math in 1946.

4. Swami Gambhirananda, Holy Mother Sri Sarada Devi (Madras: Sri

Ramakrishna Math, 1953), 138.

5. Sailendra Nath Dhar, A Comprehensive Biography of Swami

Vivekananda, 2 vols (Madras: Vivekananda Kendra Prakashan, 1990), 1.209.

6. Life

of Sri Ramakrishna, 599–600.

7. The Complete Works of Swami

Vivekananda, 9 vols (Calcutta: Advaita Ashrama, 1–8, 1989; 9, 1997), 7.248–49.

8. Ibid., 8.401.

9. ‘The Motivation Behind Vivekananda’s Wanderings in the West’, Indian Journal

of American Studies (Hyderabad), July 1981.

10. Complete Works, 1.20.

11. Ibid., 7.454.

12. Ibid., 5.33.

13. Ibid.

14. His Eastern and Western Admirers, Reminiscences of Swami Vivekananda

(Calcutta: Advaita Ashrama, 1964), 123.

15. Complete

Works,

5.83.

16. Ibid., 5.85.

17. Ibid., 5.91.

18. Dr Satish K Kapoor, Hinduism: The Faith Eternal (Kolkata: Advaita Ashrama, 2015), 315–17.

19. Sailendra Nath Dhar, A Comprehensive Biography of Swami

Vivekananda, 2.942–43.

20. See The General Report of Ramakrishna Math and Ramakrishna Mission

(April 1992), 2.

21.

Prabuddha Bharata (October 1959), ‘News and Reports’, 439–40.

This

article was first published in the January 2023 issue of Prabuddha Bharata,

monthly journal of The Ramakrishna Order started by Swami Vivekananda in 1896.

This article is courtesy and copyright Prabuddha Bharata. I have been reading

the Prabuddha Bharata for years and found it enlightening. Cost is Rs 200/ for

one year and Rs 570/ for three years. To subscribe https://shop.advaitaashrama.org/subscribe/