- Article tells about temples/ghats the Marathas built in Kashi and Why was Kashi not made part of the Maratha Empire.

- The writer is the author of a recently published book 'Battles of the Maratha Empire.'

On the eastern end

of Uttar Pradesh is situated the town of Varanasi, also variously referred to

as Kashi and Benares. Situated on the banks of the Holy Ganga, it is believed

to be one of the oldest continually inhabited places in the whole world and has

a place for Hindus higher than any other place of pilgrimage.

Kashi was a major

trade centre as also the place where Gautam Buddha gave his first sermon (Sarnath). Kashi

is associated with the river bank or ghats and hundreds of temples. It also faced

the brunt of many an invader. Destroyed time and again, only to be reborn.

One of the earliest destructions dates back to 1194 AD. Benares was then a flourishing town of the Gahadval kingdom, a part of Kannauj. Apart from hundreds of temples, it also had flourishing Buddhist monasteries–the largest one being at Sarnath. That year, Qutub ud Din Aibak, Mohammed Ghori’s general, invaded Kannauj. Jaichand of Kannauj was defeated and beheaded. Then Aibak turned to Benares and destroyed over a thousand temples, including the original Kashi Vishwanath mandir. His hordes then moved on to Sarnath and did such a thorough job that the place disappeared forever. Says Rev Sherring, “Archeologists have found everywhere traces of the great catastrophe which destroyed in one holocaust the monks, monastaries and temples of Sarnath.”

In the centuries

that followed, Benares was rebuilt and destroyed and rebuilt again multiple

times. A hundred years after Aibak,

Allaudin Khilji is believed to have demolished a thousand temples. The Kashi

Vishwanath temple was destroyed several

times, including by the Faruqi dynasty of Jaunpur and Sikandar Lodhi. Even

Humayun built a tower over a former Stupa at Sarnath. There was some resurgence

under the Mughal emperor Akbar, when many temples were rebuilt by the Rajputs

including Kashi Vishwanath.

But along came his

grandson Shah Jahan (the one who built a monument of love for his thirty eight year

old wife, who died giving birth to their fourteenth child) , and Benares saw

seventy temples destroyed. But Shah Jahan provided just the trailer. For in

1661, the Mughal throne was ascended by someone who made Akbar look truly

compassionate. He issued orders for temples to be demolished by their hundreds,

and mosques to be built in their place. No new temples were to be built.

The Kashi

Vishwanath temple was demolished and the Gyan Vapi mosque built on it. The Madhoji ka Deora (Beni Madhav temple) was destroyed and a mosque whose minarets towered above the city into the sky built over it. The destruction wrought by Alamgir Aurangzeb was on such a scale, that the holiest city of the Hindus had a distinctive Islamic look and feel by the close of the seventeenth century. He even changed its name to Mohammedabad. “There is not a single major temple in Benares which predates Aurangzeb” says Diana Elck in her book Light of

Banaras. A view echoed by Revving, where he quotes, “Although the city is bestrewn with temples in every direction, yet it would be very difficult to find twenty temples in all of Benares of the age of Aurangzeb.” The oldest city of the world is also one of its newest.

But while

Aurangzeb destroyed many temples, he also spent twenty-five years fighting the

Marathas in the Deccan. By the end of it, the Mughal Empire had fallen and

dissolved into various independent and semi independent states who accepted

Mughal suzerainty only on paper. Over time, Benares went to a family of

Bhumihar zamindars who established the Narayan dynasty, but they ended up being

vassals of the far more powerful Nawab of Awadh in the 18th century.

Cultural contributions of Marathas

Being Hindus

themselves, the importance of Benares was not lost on the Marathas. By the

eighteenth century, they had become the dominant power in central India and

could, in fact did, seriously consider extending their political control over

Benares. But although they did not physically annex it, their clout at Delhi

and Awadh, finances and control over Malwa meant that their contribution to the

town of temples was second to none.

“Modern Benares is largely a creation of the Marathas,” says the historian AS. Altekar. By the end of Aurangzeb’s rule, the city had lost much of its older temples and ghats. The Marathas carried out rebuilding on a grand scale in the eighteenth century and Benares once again regained its ‘Hindu look’. A large number of structures were also added by Biharis, Bengalis and Rajputs - mainly in the 19-20th centuries.

The Narayan dynasty for instance, contributed much to the town, including land

for the Benaras Hindu University.

The Maratha connection to Benares goes back to at least 1590, when Narayan Bhatt assisted Rajput Todarmal in rebuilding the Kashi Vishwanath temple (which had been destroyed by Sikander Lodhi and which was in turn destroyed by Aurangzeb). He was the grandfather of Gagabhatt, who presided over Chhatrapati Shivaji’s coronation ceremony in 1674. Chhatrapati Shivaji is himself known to have halted in disguise at Benares after escaping from Agra, on his way to the south.

Although not one to base any decision solely on emotional reactions, the destruction of temples in Kashi and Mathura played an important role in Shivaji’s decision to open hostilities against the Mughals in 1670.

Following the

death of Aurangzeb, Peshwa Balaji Vishwanath visited the much weakened Mughal

emperor. He too stopped at Varanasi and saw the ruined ghats and displaced

temples.

Raja Ghat made by Rajirao Balaji in 1720.

Raja Ghat made by Rajirao Balaji in 1720.

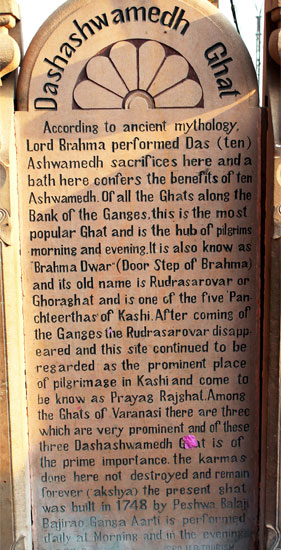

A series of ghats along the river bank gives Benares its distinct look, familiar in many a photo. The Dasashwamedh, Scindia, Bhosale, Ahilyabai, Manikarnika to name a few. All of them have a Maratha connection –

Dasashwamedha ghat was built in 1748 by Peshwa Balaji Bajirao.

Dasashwamedha ghat was built in 1748 by Peshwa Balaji Bajirao.

1. Manikarnika ghat – built by Sadashiv Naik under orders from Balaji Vishwanath Peshwa.

2. Bhosale ghat – built by the Bhosales of Nagpur.

3. Scindia Ghat – built by the Scindias of Gwalior.

4. Ahilya Ghat – built by Ahilyabai Holkar.

In fact the scale of Devi Ahilyabai Holkar’s works deserves a separate mention.

1. Rebuilding /

renovation of Manikarnika and Sitala ghats.

2. Built the

Ahilya ghat.

3. Built the new

Kashi Vishwanath temple and Shri Tarakeshawar temple.

4. Built Dharamshalas-Rameshwaram,

Kapildhara and Uttar Kashi in Benares.

5. Built nine rest

houses.

The Kashi

Vishwanath temple built by her was a new structure, close to, but separate from

the one destroyed by Aurangzeb. It has important contributions from a number of

noted luminaries. The temple bells were donated by the Raja of Nepal, as is the

large Nandi outside it. The gold for gold plating of its spires was donated by Maharaja

Ranjit Singh of Punjab. An intricately carved stone enclosure around the

Gyanvapi well was sponsored by Baiza Bai Shinde of Gwalior.

Other notable

contributions of the eighteenth century include -

1. Bajirao ghat

and Dattatrey temple by Peshwa Bajirao I.

2. Durga, Brahma

and Trilochan ghat built by Narayan Dixit Patankar.

3. Balaji Bajirao

built the Tulsi Ghat.

4. Sakshi Vinayak

temple.

5. Annapurna

temple.

Many important contributions were also made in the nineteenth century. Such as temples built by Amrutrao, a brother of the last Peshwa–Bajirao II. The last Peshwa also built the Bhaironath temple in Benares in 1825. Other notable Maratha contributions of the nineteenth century include the Gwalior Ghat built by Jivaji Rao Scindia and the Gangamahal Ghat built by the Munshi of the Nagpur Bhosales, who also built the Munshi ghat.

The original Beni

Madhav temple had been destroyed by Aurangzeb (apparently the temple stood

there since the fifth century AD), and replaced by the Alamgiri mosque. The

mosque still stands, the new Bindu Madhav temple is a small structure nearby

also built by the Marathas. Narayan Dixit Patankar also built some facilities

near the Panchganga Ghat for pilgrims.

Pilgrimages

The other area

where the Marathas made a major contribution was in pilgrimages to Varanasi, as

also Gaya and Prayag. Given their distance from Maharashtra, many would visit

all three places in a single trip. The Marathas brought huge numbers of

pilgrims to these pilgrim sites. Narayan Bhatt, mentioned earlier, also

composed the Tristhalisetu, a treatise on conducting pilgrimage to

Kashi, Prayag and Gaya.

The conquest of Malwa and the Maratha presence in Delhi freed up pilgrimage routes hitherto considered dangerous under Mughal rule. Every Maratha chieftain small or big used to patronize and sponsor pilgrimages. With expenses such as tolls, pilgrim taxes, Pandit fees etc being taken care of by the sponsor – it made it possible for many poor people to undertake pilgrimages which could be four or five months. These had the added advantage of travelling under the security of armed personnel, accompanying the chief dignitary. The roads were, many a times, infested with wild animals and bandits, making small private tours impossible. Often, pilgrims would follow a regular army, hanging on to the shelter provided by it on the long route north.

Marathas topped the number of pilgrims headed to these sites. Pilgrimages happened every year, a few examples will suffice to show the numbers headed to the Kashi-Prayag-Gaya triumvirate. In 1743, nearly seventy thousand pilgrims accompanied Nanasaheb Peshwa to Gaya, followed by Prayag and Benares. Other large pilgrimages included one by Narayan Dixit Patankar, which had fifteen thousand pilgrims. Raghuji Bhosale’s mother went on a pilgrimage to Prayag with twenty thousand followers.

Vishnupad Temple Gaya, Bihar made by Ahilyabai Holkar in 1787.

Vishnupad Temple Gaya, Bihar made by Ahilyabai Holkar in 1787.

One of the most famous pilgrimages taken to Kashi and Prayag was by Radhabai, the Peshwa Bajirao’s mother in 1735. This was just two years after Peshwa Bajirao had defeated Mohammed Khan Bangash and established himself in Bundelkhand. The pilgrimage was as much a political statement as religious!

In February 1735 she left Pune and travelling via Burhanpur, reached Udaipur and was well received there by the Rana of Udaipur. She then travelled to the first place of worship in her route – Nathadwara. Proceeding on, Mathura was visited after travelling via Jaipur. Radhabai also visited Benares, Prayag and Gaya on this trip. Mohammed Khan Bangash provided her with a thousand man bodyguard, lest something happen to her and Bajirao come visiting!

A combination of

resources, political clout and good relations with the local ruling dynasty of

Varanasi enabled the Marathas to contribute much by way of temples, ghats,

pilgrimages. The actual annexation of the place to the Maratha Empire could not

be carried out, although it was their ardent desire to do so. We shall see this

in the next section.

Why was Benares not annexed to the Maratha Empire?

After noting the high number of temples and ghats as also the huge number of pilgrims which headed to Benares in the eighteenth century–two obvious questions come to mind.

Why wasn’t it annexed to the Maratha Empire

What about the

mosque built by demolishing the original Kashi Vishwanath temple?

Right from the

days of Chhatrapati Shivaji, it was an ardent desire of the majority population

to free Kashi, Mathura and Prayag from Muslim rule. We find that almost as soon

as the Marathas were in a position to make demands of the Mughal emperor, the

annexation of Kashi, Mathura, Prayag and Gaya is a permanent theme.

In 1736, in the

letter demanding that Malwa be ceded to the Marathas-the cessation of Kashi,

Mathura, Prayag and Gaya is mentioned.

In 1741, the Peshwa Nanasaheb in a letter to the Maratha agent at Delhi, Hingne, says “Sawaiji has agreed to obtain a cash payment of twenty lakhs from the imperial treasury, the remittance of pilgrim tax at Prayag and the cession of Benares.”

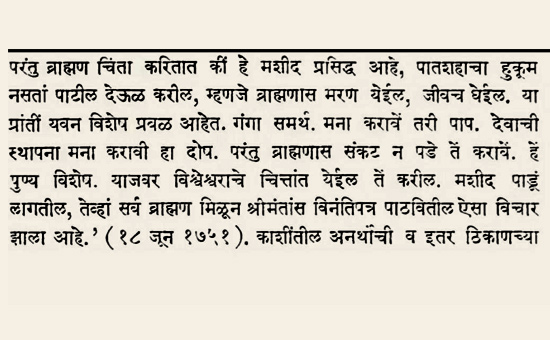

In 1751, when

Malharrao Holkar was in the doab and the Marathas were making considerable

inroads, there was strong speculation that Holkar would level the Gyan Vapi

mosque. But considering that Muslim rule was quite strong in the region, the

locals were not very enthusiastic about this plan.

Peshwe Dafter, Credits GS Sardesai.

Peshwe Dafter, Credits GS Sardesai.

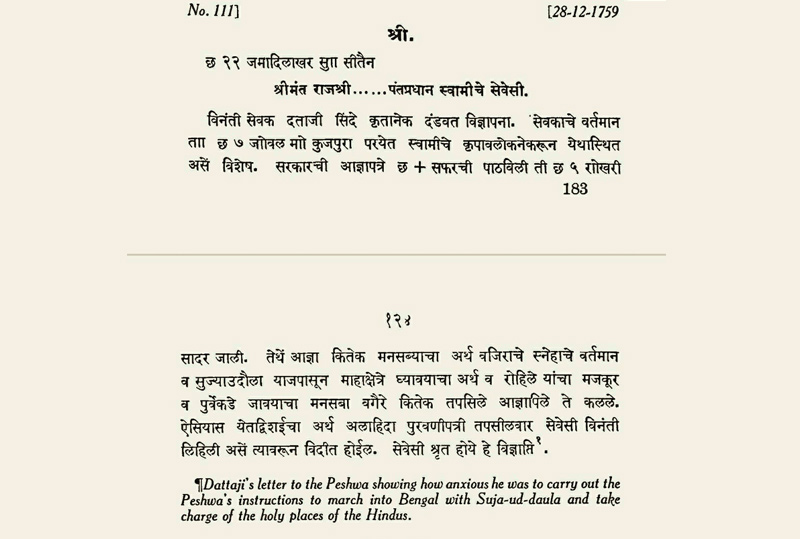

In 1759, when the

Marathas had achieved considerable clout in north India, and in fact their

armies had touched the Indus in Punjab, they chalked out plans to enter the

Ganga Jamuna doab, wrest control of the holy places and push on towards Bengal.

Says Dattaji Scindia in a letter to

Nanasaheb Peshwa below.

Peshwe Dafter, Credits GS Sardesai.

Peshwe Dafter, Credits GS Sardesai.

After the conquest

of Delhi in 1771, Peshwa Madhavrao congratulated Mahadji Scindia. At the same

time, he enquired what was being done about the Hindu holy places still with

the Nawab of Awadh.

Peshwa Madhavrao’s last will of September 1772 states, “The two holy places Prayag and Benares must be freed from Muslim control. This was the ardent desire of my sires and now is the time to carry it out.” The statement also confirms the wish of

earlier rulers to free these places

A military invasion of Awadh was definitely planned post Panipat – and in fact was one of the reasons for the Jihad to be declared that year against the Marathas. The Bangash, Rohillas and Shias of the Ganga – Jamuna doab, who otherwise were sworn enemies of each other, dutifully lined up behind Ahmed Shah Abdali once the “Islam in danger” cry went up. The results at Panipat finished any plans to invade Awadh in 1761.

The reason more invasions were not mounted were two fold–one was the distance of Prayag and Benares from Pune. The Marathas needed to have a very strong fortified base at least in the Bundelkhand to be able to launch repeated attacks on Awadh. Secondly, they had managed to attain much political dominance by playing off the Irani and Turani factions of the Mughals against each other. Attacking the doab meant opposing all of them together – as happened at Panipat.

During the 1740s and 1750s, when the Marathas were at their strongest, they were also somewhat allied with the Nawab of Awadh-Safdarjung. He was providing them support to put down the Bangash and Rohilla tribes in today’s western Uttar Pradesh. From the point of view of the Nawab, granting Benares, Prayag and Mathura meant “giving in to the Hindus”, but also meant being hemmed in from all sides. It also meant that the Marathas could then influence Bengal even more thoroughly.

By the time the

Marathas recovered and became powerful once again in Delhi, a decade had

passed. In the meanwhile, the British had defeated the Mughals and the Shuja ud

Daulah at Buxar and become masters of Bengal. It seemed as if they would now

press on to Delhi via the grand trunk road. But Clive aborted that plan.

The Nawab knew that Mahadji Scindia having taken Delhi and crushed the Rohillas into submission, would now head to Kashi. So the proud ruler of Awadh turned to Warren Hastings. Says Shuja ud Daulah to Warren Hastings “My enemy is situated close to me, nothing but the river Ganges is between us, and they call upon me to surrender Kora, Allahabad and Benares, to give them my settlements with the Rohillas……. I do not in the least consent to these things.” (Town Kora is in Uttar Pradesh. Holkar was defeated by East India Company in 1764)

And so saying, to prevent Benares from going to Mahadji Scindia, Nawab Shuja ud Daulah joined the East India Company. “The British victory at Buxar is in fact my victory” is another of his gems.

Benares had been

under the Narayan Dynasty, which held the Benares jagir for the Nawab of Awadh.

Under the East India Company, they became quasi independent rulers.

A last attempt was

made to obtain possession in 1781, when Nana Phadnis demanded Benares, Gaya and

Prayag from the British and in fact was willing to purchase these places. But the

deal never materialized.

The situation for

the Hindus of Benares actually improved when it passed from the Nawab of Awadh

to the British. Having continued with Raja Chet Singh, the older building works

could continue and reach greater heights. The threat of the Nawab of Awadh

disappeared and many temples were built in the nineteenth century also, with

the nearby Maratha state of Gwalior being a major contributor.

To read

all articles by author

To visit Author Aneesh Gokhale

website

To read

all articles on Maratha History on site

Also read

1. Kashi

Yatra in the Peshwa period

2. Why

Ahilyabai Holkar was a great woman

References

1. Banaras – City of light: Diana Eck

2. Warren Hastings

& Oudh: C. Collin Davies

3. Persian Records

of Maratha History: Dr PM Joshi

4. IHRC – Vol 14

5. British

Administration of Hinduism in North India: Katherine Prior

6. Uttar Pradesh Gazetteer – Varanasi (1965)

7. Benares, Sacred

city of Hindus: MA Sherring

8. Peshwe Daftar:

GS Sardesai

9. A New History

of Marathas, Vol 2: GS Sardesai

10. Kashi Yatra

(article by Dr Uday Kulkarni)

11. Life &

Life Work of Shri Devi Ahilyabai Holkar : V.V Thakur

12. Marathi

Riyasat, Vol 5: GS Sardesai

13. A handbook of

Benares: Rev Arthur Parker

14. The Coronation

of Chhatrapati Shivaji: Gagabhatt / VS Bendrey

15. Calendar of

Persian Correspondence