- The town of Kashi holds eternal

charm to the Hindu pilgrim. A single visit to the city is rarely enough. The

old city with its tortuous lanes that lead to the innumerable ghats on the

river front have held visitors in awe that is almost magical.

It is time to talk of Kashi, a city that lives where the river Ganga turns north, so that the entire riverfront at the spot faces east towards the rising sun. The age-old tradition of offering ‘arghya’ on the bank of the river was easier, as the devotees could face towards the sun. It is said that the city began at the Raj ghat to the north of the city where the river Varuna joins the Ganga. From here to the Assi ghat where the river Assi joins the Ganga, is ‘Varanasi’ – a word that originates from Varuna and Assi and gives us the geographical limits of the city.

(The article is excerpted from the author’s forthcoming book ‘The Extraordinary Epoch of Nanasaheb Peshwa’)

Present day ghats of Kashi

Present day ghats of Kashi

From

times immemorial, the Kashi-yatra was an integral part of life for the Hindus.

As the oldest continually inhabited city in the world, Kashi along with Prayag,

Gaya, Mathura and Ayodhya were places that were held in great reverence.

Recent excavations have shown the earliest parts of Kashi were located near the Rajghat towards the river Varuna's confluence with the Ganga. The eighteenth century was marked by the spread of the Maratha power in the north up to the Gangetic doab and the number of Marathi people who began travelling to this place grew year after year.

The

Peshwas devoted considerable attention to the city and spent money in the

construction of ghats and places for pilgrims to stay. This was true through

Indian history, when powerful kings and chiefs always added to the city, and

many of these structures stand there to this day. Among the Peshwas, the desire

to obtain possession of Kashi from the Nawab of Awadh was particularly strong.

Nanasaheb Peshwa strived to obtain it as did his son Madhav rao.

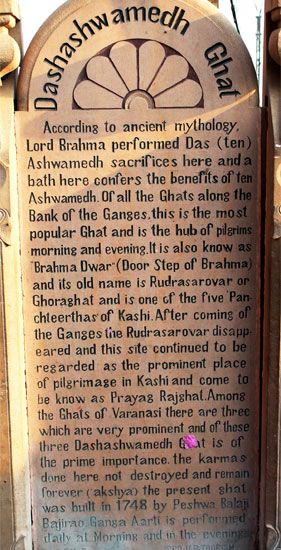

Dashashwamedh

Ghat was made in 1948 by Peshwa Balaji Bajirao.

Dashashwamedh

Ghat was made in 1948 by Peshwa Balaji Bajirao.

For

the common pilgrim, the journey to Kashi was not easy. The roads were uneven,

there were thick forests and mountains, great rivers to cross and innumerable

dangers from wild animals or dacoits, who came in swarms of hundreds and

swooped down on a group of travellers, merely looting them if they were

fortunate, and killing them if they resisted.

These

dangers meant that a large group had to be accompanied by a fairly large number

of armed men who might be able to stave off such attacks. The pilgrims were

both men and women, often elderly, besides the mendicants and gosains who

travelled from place to place. There were bullock carts and palanquins and

horses that the pilgrims used, however, there was still a large number that

walked.

It

was not a short journey either. The period after the Dussehra festival was

chosen as the favourable one, since the weather was better, and often, if one

was fortunate, one could be sheltered by a Maratha army travelling north. It

was difficult for an army to shake off the highly motivated pilgrims from

following them. The travelling banjaras who brought their bazaars along to feed

these armies - literally a city on the move - made it a little bit easier for

the pilgrims too to accomplish the Kashi yatra.

Dev Deepavali Festival Kashi 2013.

Dev Deepavali Festival Kashi 2013.

Around

1734, when Baji rao made his mark north of the Narmada, Narayan Dixit Patankar,

the guru of the Peshwa and his brother Chimaji, left for Kashi. A house was

found for him by Sadashiv Naik, a prominent banker who stayed in Kashi. Nanasaheb Peshwa too considered Narayan Dixit as his guru. Innumerable letters through the eighteenth century testify to the wide-ranging activities of this Dixit Patankar family. Narayan Dixit himself is said to have died around 1747, at the age of nearly a hundred years. To this day, one can find a lane in the old city of Kashi named ‘Narayan Dixit Lane’. His son Vasudeo remained the Peshwa’s confidante throughout Nanasaheb’s years.

A few months after Narayan Dixit went to Kashi, he was followed by the Peshwa’s mother Radhabai who passed through Udaipur, Jaipur, Mathura and Prayag before reaching Kashi. She was accompanied by her son-in-law Abaji Naik Joshi, whose father was Sadashiv Naik of Kashi. Abaji’s brother, Babuji Naik, also accompanied her.

Radhabai’s pilgrimage was not just of religious importance. During her journey, she was greeted at the palaces of the Rajput rulers with great respect and hosted like the mother of an important king. In Udaipur and Jaipur, matters of diplomatic import were also discussed and proposals exchanged on how the Mughal power was to be tackled. The discussions held at this time led to the Peshwa’s visit to Jaipur and Udaipur the following year.

Ghats Kashi.

Ghats Kashi.

From Jaipur, she was escorted till Mathura by Sawai Jaisingh’s own officials and from there onwards the journey was accomplished with the protection offered by Muhammad Khan Bangash who was the subedar of the Mughal province of Allahabad. Bangash himself had been defeated by Bajirao a few years ago at Jaitpur in Bundelkhand but given safe passage on the assurance that he would not attack Bundelkhand again. Bangash said, ‘Baji rao ji’s mother is like my mother’

and escorted her to Prayag and onwards to Kashi. During the time she spent

there, she scrupulously avoided getting into local disputes but gave donations

to the local people and places of worship.

Kashi

was a city that had a large number of Brahmins, called the Gangaputra, whose

livelihood depended on the pilgrims visiting the city. These Brahmins of the

north, also called the Panch-gauda

were the chief priests of the city until the end of the seventeenth century.

In

early eighteenth century a large number of Brahmins from the south began to

migrate to Kashi and perform religious rituals of the pilgrims coming from the

Deccan. The south Indian Brahmins, called Panch-dravid, from Andhra, Telanga, Tamil Nadu and Kerala,

Maharashtra and Gujarat/Rajasthan, over time became rivals of the Gangaputra

Brahmins.

Matters

went before local courts and before the Qazi of Varanasi, who first ruled in

favour of the Panch-dravid. Two years later the two sects of Brahmins resolved

that the rituals by the river will be performed by the Gangaputra Brahmins

only.

From

the year 1730, Sadashiv Naik built many buildings and ghats in Kashi from funds

sent to him by Bajirao Peshwa. Three ghats were planned, however, local

rivalries created obstacles in the path.

Until

1735, Naik writes, he had built and completed two ghats - the Dash-ashwamedh

ghat and the Manikarnika ghat. The Dash-aswamedh ghat was built for

a saint named Advaitanand Swami. There was no permission to build at

the Panchganga ghat so Naik began creating a garden on a land measuring three

bighas, where he found that two thousand pilgrims could have their meals at one

time.

According

to a letter from Narayan Dixit to Nanasaheb Peshwa, Radha bai spent the Indian

month of Kartik in Kashi, when the pournima is a major festival with oil

lamps lit on its many ghats. Dixit was annoyed however, that she did not ask

him about which Brahmins were deserving of her alms. ‘The Maharashtra Brahmins got nothing, the Chitpavans were paid five or ten’, he wrote. The

reason behind his complaint was that the money spent did not go to deserving

hands and therefore, her fame did not spread as it should have. Radhabai

perhaps took the advice of the Gaud Brahmins, who lived there in large numbers.

Dixit says he did not try to stop this as otherwise, the Gaud Brahmins would

have made him leave Kashi.

In another letter from Naik, Bajirao and Chimaji come in for high praise for their support - at such a young age – to build eleven Brahmapuris where sanyasis can stay. The building of ghats continued at this time. Even then, on the Kartik pournima

day Naik writes, ‘when the lights are placed, it becomes like Shri Kailas. All those who come from Maharashtra say these ghats are Baji raoji’s’. Naik also speaks of developing the Shri Nagesh temple – perhaps a reference to the Nagesh Vinayak temple. Naik also prays for the Peshwa and sends him water from the Ganga.

Temple in the Ganga is unique.

Temple in the Ganga is unique.

The attraction for Kashi was very strong among the Peshwas through the eighteenth century beginning with Balaji Vishwanath, up to the last of the line. While Nanasaheb was the only Peshwa in the eighteenth century (in the nineteenth century, Amrut rao Peshwa and Chimaji Appa II stayed in Kashi) to have visited Kashi during his campaign to Bengal, besides Radha bai, two ladies from the Peshwa family visited Kashi. One was Nanasaheb Peshwa’s mother Kashibai, and the other was Sagunabai, the widow of Baji rao’s son Janardan who died sometime after 1748.

Of these, the story of Kashibai’s travels are of a curious nature. She left Pune on 16 February 1746 with her brother Krishna rao Chaskar Joshi. She took the route of Kaigaon-Toka, Ellora, Burhanpur, Sironj and Kalpi, where she entered the doab and reached Prayag. A large group of ten thousand pilgrims accompanied her, and a passport for them was obtained from the Emperor in Delhi. From Kalpi onwards, she was escorted by Naro Shankar who was in charge of Jhansi. From Prayag, she visited Kashi, returned to Prayag and went back to Kashi.

In Kashi, Raja Balwant Singh gave Kashibai a place to stay in his own palace. At this time, of the large number of horses and camels with her, five horses were stolen. The lady’s aides blamed Balwant Singh. The Raja then managed to get two of the horses back, but hearing of the accusations against him, was annoyed. The Awadh Nawab Safdar Jung was the subedar of the province and Balwant Singh complained to him and asked him to get Kashibai to leave. However, it was the middle of the monsoon and travel was not yet possible.

Despite Balwant Singh’s resistance, Kashibai continued to sojourn in Gaya and Kashi that whole year. Innumerable letters from the Peshwa and other officials reached Kashi asking her to leave the place.

However,

Kashi bai refused. Seeing her determination, eventually her brother Chaskar

Joshi threatened he would drown himself in the Ganga if she did not agree to

leave the place. Finally, Kashi bai left for Prayag in the Indian month of Magh

(around February 1747) and then reached Pune. The total journey occupied nearly

fifteen months.

Kashi

held an attraction for the Marathas in general and the Peshwa family, so that

Sagunabai also visited Kashi during the turbulent months of 1757 when Ahmed

Shah Abdali came to Delhi, looted it and went on to Mathura where he massacred

thousands of pilgrims and Hindus.

Even later, we have stories of families of Maratha chiefs visiting the holy place. Raghunath rao’s wife Anandibai died in 1794, yet her ashes were not immersed straightaway and left with an officer at Nashik.

When

her son Baji rao II became Peshwa in 1796, he arranged for her ashes to be

taken to Kashi for dispersal in the Ganga. The last of the

Peshwas, Amrut rao and Chimaji Appa II also spent their last days at Kashi and

left behind many ghats and buildings that can be seen in the city to this day.

References

1. Selections from the Peshwa

daftar, Volumes 18, 30 and 43.

2. VK Bhave’s ‘Peshwekaalin Maharashtra’

3. The Era of Baji rao – Uday S. Kulkarni

4. The Extraordinary Epoch of

Nanasaheb Peshwa (to be published soon).

All pictures are courtesy Sanjeev Nayyar

Also read

1. Why does everyone love Varanasi

2. in today's times Kashi and Prayag Yatra

3. Dev Deepavali Kashi