- This battle was

fought in 1803, at Assaye in Maharashtra, between British General Arthur

Wellesley and the Marathas namely the Daulatrao Scindia & Raghuji Bhonsle. In

later life, Wellesley was slated for greater glory as the man who defeated

Napoleon at Waterloo in 1815. When asked once of which of the many battles he

fought was his toughest, he gave a simple one-word reply; ‘Assaye’.

To read The

Battle of Assaye Part One

We ended the

first part of this narrative with Arthur Wellesley leading his men eastward

from the small town of Nalni, north of the Godavari towards Jaffrabad on the

morning of 23rd September 1803. The armies of Daulatrao Scindia

including his regular infantry battalions had descended the Ajanta ghat and

come south with Bhonsle’s cavalry, some of Begum Samroo’s trained infantry

brigades and a large irregular cavalry of Pindaries that harassed the British

supply chain. In fact, the Pindaries had at one point even relieved the Mysore

cavalry of about 250 of their horses! Scindia intended to enter the British

ally Nizam’s territory and this is precisely what Wellesley and his colleague

Stevenson were trying to prevent.

The war was not going well for Daulatrao Scindia. He had lost Aligarh and Delhi, he also lost many of his European commanders who resigned or deserted and joined the English owing to the Proclamation that anyone of British ancestry would be counted as a traitor if he did not join them. The aggressive plan of Governor General Lord Mornington, also Wellesley’s elder brother, aimed at subjugating all the Indian princes. His rapid success against Tipu Sultan at Srirangapatnam had led to an encirclement of the Maratha power and after Bajirao Peshwa signed the Subsidiary treaty in 1802, the British had the legal cover needed for intervening in Maratha affairs.

The entire

Scindia-Bhonsle army lay camped between the towns of Bhokerdan and Jaffrabad

with the regular infantry and artillery in the tongue of land in the fork

between the Khelna river to the south and the Juee river to the north. Their

regular infantry numbered over ten thousand men led by Colonel Pohlman and

Dupont, both Frenchmen employed by Scindia. There was also the Maratha cavalry

and a large number of Pindaries who did not participate in any actual war. Wellesley

had with him a smaller contingent of infantry and artillery, manned by the 74th

an 78th Highland regiments and a combination of Indian and European

cavalry. The total number of men with Wellesley were less than five thousand.

The men that

Wellesley had to watch out for was the Maratha infantry – a sea change from the

days of Panipat when infantry was not as important as the cavalry. Colonel

Collins who had been a Resident with Scindia had met with Wellesley at

Aurangabad, and here is what he had said, ‘ I tell you General, as to their cavalry you may ride over them wherever you meet them; but their infantry and guns will astonish you.’

The British narratives of the battle are many of which

one is by Blakiston, a British officer with Wellesley. He notes in his memoirs

how bleak the country was with wars and famine, and commenting on the karmic

attitude of the Indians, he thought it reflected on the patience of the Hindu;

‘This patience under suffering, this

composure.. within the jaws of death, are prominent characters of the Hindoo,

and ought indeed to put to shame those among their conquerors, who boasting

higher virtues of courage and virtue, pretend to look down upon them with

contempt. No one meets death with less apparent dread than the Hindoo; and when

imbued with a sense of honour, as among the military cast(e)s, no one can

display more heroism. I have seen them refuse quarter, when the European would

have courted mercy even in chains.’

On 22nd September,

Wellesley’s decision to divide his armies was on the presumption that Scindia

was retreating to regroup with Bhonsle’s armies. He therefore headed east himself

and sent Stevenson westward, hoping to catch the retreating armies in a pincer

movement. He planned the final attack on 24th September, when he

expected both armies to be in the correct position. Marathas also expected the

battle to be on Saturday the 24th. However, when Wellesley reached

Nalni on the 23rd morning after a fourteen-mile march, he received

intelligence that the regular Maratha army was just eight kilometres away. At

the same time, Stevenson was that much further away to the west. It was a

critical moment, and a decision had to be taken on whether to fall back, or

attack. Wellesley decided to attack immediately.

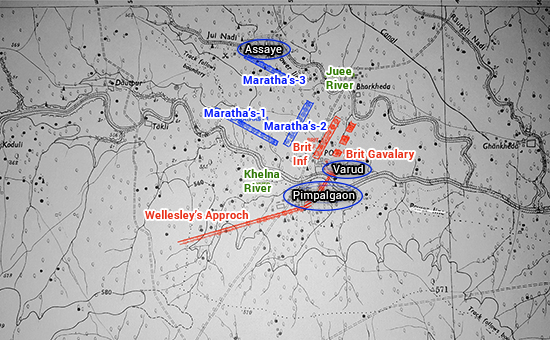

Battle Plan Assaye. Pic courtesy Survey of India.

Battle Plan Assaye. Pic courtesy Survey of India.

Daulatrao was with his army near Assaye till the 22 September. That day he moved back towards the Ajanta Pass to the north and left his army under two French captains. At noon, the British from a high ground over a mile from the Maratha position, had their first glimpse of the Maratha army across the river Khelna. They were gathering their tents and did not expect a battle that day. An encampment in the shape of a parallelogram between the two rivers was nearly two miles long with a huge number of people within. Soon after

sighting the British, the tents disappeared and the Maratha infantry

formed two lines parallel to the Khelna, facing south towards the British. The

second line of the infantry on its left touched the village of Assaye near the

river Juee. To the right of the Maratha infantry was a large mass of Maratha

cavalry extending till the village of Bhokerdan.

Wellesley cast

his eye on this formation and planned to attack from the left flank of the

Marathas, which he perceived as the weakest and away from their large cavalry

on the right. For this he had to make a diagonal march across the front of the

Maratha column towards the river Khelna near the village of Pimpalgaon. He

hoped to attack from the narrower part of the fork formed by the two rivers

with the steep scarps of the river protecting his own flanks. The British army

found Pimpalgaon and Varud, two villages on either side of the Khelna, where

the river was fordable and using the scarps and the hamlets, he protected his

army while crossing over.

Abandoned British Cannon at Pimpalgaon. Pic courtesy Author.

Abandoned British Cannon at Pimpalgaon. Pic courtesy Author.

The Marathas, surprised by the British decision to come to battle the same day, responded quickly. Seeing the British aiming to approach their left wing, they changed their front in good order, now facing east. The Maratha army still seemed not entirely battle ready and this enthused British ranks. However, as soon as the British began to ascend the bank of the Khelna, they were hit by a gun brought on for the purpose. Wellesley’s orderly’s head ‘was carried off’ by a cannon ball, although the body remained strapped to the horse.

By the time, the

British had reached the top of the river bank, the

Marathas had completed the change in their position – now with their

right wing on the Khelna and the left wing on the village of Assaye. Wellesley

had not expected this and giving up his idea of attacking the left flank, he

prepared to face the Marathas head-on in two infantry columns with the cavalry

in reserve. Wellesley sent pickets of men to the right, placing the 74th

Highlander regiment on the right, while the cavalry was sent to support it. He

was on the left flank leading the 78th Highlanders against the

Maratha right wing. His own centre had many Indian troops.

Soon, a steady

fire from the Maratha guns began to find its mark among British lines.

Wellesley had advanced by his left wing, and found his right unable to keep up

with his progress. The gunners in the Maratha

centre, who pretended to be dead, were also turning around to fire at

the left wing of the British 78th regiment that had already crossed

their line.

As the British

spread out obliquely towards the two rivers, gaps appeared in their formation

and the 74th Highland went considerably to the right towards the

Juee river. The hundred gun Maratha artillery now

began to thunder, finding its mark. The British infantry soon came in

contact with the Maratha right, the last bit of fighting was with bayonets. The

main damage to the British was on their right flank near the Juee, and the 74th

Highland could not move forward and sustained heavy casualties from the Maratha

fire. This was followed by a Maratha cavalry charge causing the 74th

to sustain very high casualties. A British sergeant name Swarbruck wrote later,

‘Our infantry suffered severe, the right brigade (74th) charged

but were forced to retreat for they were nearly all killed or wounded.’ The

Marathas moved forward and cut down the retreating Highlanders. At this stage some of the British cannons fell in the hands of Maratha

gunners who turned them round to fire and kill British soldiers. Nearly

all officers of the 74th were killed.

It was the

moment when one officer’s gallantry saved the British right. Colonel Maxwell with

his 19th Dragoons charged at this point, deflecting the Maratha

attack but suffering their fire in the process. Wellesley came to the spot and

said to him, ‘you must make the best of your cavalry or we shall be done’.

Maxwell charged over ‘poor wounded men’ from his own army, as he led the attack

on the Maratha cavalry.

The moment was

critical. Maxwell with the 19th Dragoons, charged at the Maratha

left and pushed it back across the Juee river. The Maratha left wing had been

broken although most of the British casualties were in the fight against them.

The Maratha centre however, still held fast. It changed its position once again

so that its right wing now touched the Juee river and the left wing was at

Assaye. A gun battle ensued once again, and with the British cavalry away in

pursuit of some of the Maratha army, any strong movement by the Maratha cavalry

at this time could have turned the battle in their favour. Wellesley reformed

his army and some of his cavalry to launch fresh attacks, during which process

his horse Diomed’s leg was carried away by a cannon shot. However, the Marathas

did not wait for the fresh charge and retreated, crossing the Juee, vacating

the battlefield and discarded almost ninety cannons which the British later took

over.

During the Maratha retreat,

Colonel Maxwell once again led a cavalry charge with his 19th Dragoons.

The Maratha line stood poised to receive the attack with their bayonet and

fired at the advancing column. Maxwell was shot when leading this attack and

flung his arms on being fired at; this action led his men to think he had

ordered a retreat. The 19th therefore turned back in a hail of fire,

running parallel to a severe Maratha fire, sustaining heavy casualties.

Although the

last British charge ended with the death of Maxwell, the Marathas withdrew and

left their camp equipment on the field. Nearly 2000 of the 4500 men in the

British army were either killed or wounded and there were nearly four to five

thousand Maratha casualties on this small battlefield. The Maratha horse did

not find the space to operate their large army in the region and many of their

men did not come to battle with so narrow a front line. The choice of the battleground was thus favourable for the small

British force, which nevertheless sustained very high casualties.

Wellesley had gambled by attacking immediately with a much smaller force and

emerged with success. His experience in Mysore had convinced him that attack

was the best form of defence when fighting Indian armies.

The battle of Assaye was followed in the north by the fall of Agra and the defeat of Scindia’s commander Ambaji Ingle at Laswari in October. By early November, Scindia had lost at Aligarh, Delhi, Assaye, Agra and Laswari. It is said some of the troops from the Deccan fought at Laswari. Of all these, the highest casualties suffered were at Assaye. The final British attack was against the combined army of Daulatrao and Raghuji Bhonsle at Argaum on 29 November and at the fort of Gawilgarh in present day Vidarbha in the first half of December 1803. Both the battles were stiffly fought and with the capture

of Gawilgarh, the power of both Scindia and Bhonsle was broken.

Wellesley had captured the chain of forts in the Deccan comprising Ahmednagar,

Daulatabad, Burhanpur, Asirgarh and Gawilgarh. Both Scindia and Bhonsle signed

treaties with the East India Company before the end of 1803. On 17 December Raghuji signed the treaty of Deogaon, handing over his

holdings in Odisha to the British, and on 30 December Scindia signed a

treaty of peace at Anjangaon. Scindia never fought the British after this.

From the treaty

of Vasai to Anjangaon, it had taken the British 364 days to subjugate Scindia

and Bhonsle. The Peshwa was thereafter saddled with an overbearing foreign power

that monitored his every act. Bhonsle and Scindia lost extensive provinces all

over India but were allowed to keep some of their territory with limited

autonomy. Holkar did not fight in 1803, however, the British campaign against

him opened the next year. He proved a tough adversary for the British and

handed them several reverses before his final defeat.

The battle of

Assaye and the second Anglo Maratha war broke the Maratha Empire and the era of

British dominance was upon India. The key factors

for a British victory, according to Prof. Randolf Cooper who has

authored a book on the 1803 war, was neither their discipline or drill but the

superior British ‘credit’ from their global commercial operations that enabled

the capture of the Indian military economy. He debunks the hypothesis of

superior British artillery, even contesting whether there was parity. The desertion of military commanders from Scindia’s army

to the British on the eve of the battle is a lesson for all sovereign nations

not to tie national security to the apron strings of foreign arms or foreign

experts. Alas, we are still some way from achieving this.

In later life,

Wellesley was slated for greater glory as the man who defeated Napoleon at

Waterloo in 1815. When asked once of which of the many battles he fought was

his toughest, he gave a simple one-word reply; ‘Assaye’. It was a near run

thing and Wellesley’s leadership on the battlefield where he had two horses

shot under him and his orderly decapitated by a cannon ball, was surely his

closest shave with defeat and possible death on the battlefield.

Musket Ball. Pic courtesy Author.

Musket Ball. Pic courtesy Author.

Assaye’s

memorial was vandalised a few years back and the graves of the 74th

Highlanders had their plaque stolen. Little remains to be seen except for the

small musket balls still found in the fields by village children who try to

sell it to History enthusiasts.

Graves with the Plaque Missing. Pic courtesy Author.

Graves with the Plaque Missing. Pic courtesy Author.

Assaye marked a turning point for Indian history and deserves

to be better known. Unfortunately, neither the place

nor the history are well known today.

To read all

articles by the Author

References

1. The Anglo-Maratha

Campaigns and the Contest for India - Randolf G.S. Cooper.

2. Aitihasik Lekh

Sangraha - Vol 10 to 13.

3. Twelve years Military Adventures - by John Blakiston.