- Starting about 1850 articles covers phases of the freedom movement in Punjab, key freedom fighters, Ghadar Party, Jallianwala Massacre.

Anti-colonial

protests and movements in Punjab, as in any other part of India, were

stimulated by a number of factors - political subjugation, impoverishment of

peasantry, drainage of wealth, repressive land revenue settlement, destruction

of indigenous industries, racial discrimination, cultural subordination, spread

of western education and the influx of democratic, liberal and rational ideas,

new means of transport and communication, rise of new social classes,

socio-religious reform movements, and emergence of new political leadership.

Although

Punjab was the last major state to be conquered by the British in 1849, it did

not lag behind Presidency towns in eliciting resistance movements against the

Raj, as and when an occasion arose. But it took some time before anti-British

feelings could crystallise into a mass movement.

The

heroic plan of Maharaj Singh (a saintly preacher) to raise a banner of revolt

against the British in Punjab on January 3, 1850, by making Bist Jalandhar Doab

as the epicenter, and Maharaja Dalip Singh (1838-93) as the leader, proved

abortive. He was deported to Singapore where he remained incarcerated till his

death on June 5, 1856.

First

published in Journal of Bharatiya Vidya Bhawan.

Revolt of 1857

The

common belief that Punjab was indifferent to the Revolt of 1857, or that it

remained loyal to the British Empire, is not wholly true, as borne out by the

researches of Dolores Domin, and others. Anti-British risings in the Punjab

Hills (Nalagarh, Kasauli and Kangra, for example), on the North-west frontier

(Naushehra and Mardan) and at Lahore, Sialkot, Ferozepur, Ludhiana, Jalandhar

and other places prove this point. The Nawabs of Jhajjar and Dadri, the Rao of

Rewari, the King of Ballabhgarh, leaders of the Meo tribe, Jats, Ranghars,

sadhus and faqirs, and the Muslim peasantry, in general, defied the British authority

by supporting the revolutionaries.

The Revolt of 1857 was suppressed but the embers of discontentment continued to burn. Sir John Lawrence sensed the gravity of the situation and informed the Home Government: “Yes, India is quiet - as quiet as gun powder.” The Kuka (Namadhari) movement upheld his prognostication.

Baba Ram Singh, leader of the Kukas.

Baba Ram Singh, leader of the Kukas.

Kuka Movement

Baba

Ram Singh (1826-85), leader of Kukas, was a disciple of Baba Balak Singh,

founder of the Namdhari sect at Hazro (Pakistan). His attempt at religious

reform and revival culminated in a dynamic protest against the Raj. He was the

first Indian to use swadeshi and boycott as political weapons, to think of

seeking foreign help for making India free, and to openly disparage the vices

of the west. He discarded the use of the British postal system, British courts

and other official institutions and even tap-water. The number of his disciples

grew rapidly and he in the eyes of the government.

Irked

by the lifting of ban on cow-slaughter, a

group of Kukas attacked the butchers of Amritsar and of Raikot (district

Ludhiana), killing and injuring some of them in the process. At Malerkotla

(district Sangrur), the crusaders, after attacking the butchers at a locality

known as Chirhimar, came into an armed clash with the authorities as well as

with a group of Pathans led by Samund Khan. The Malerkotla official who had

ordered the slaughter of an ox before Gurmukh Singh, a Kuka, was killed. Many

more casualties followed the conflict.

The

Naib Nizam of Patiala incarcerated 68 Kukas in the Amargarh fort before handing

them over to Cowen, the Deputy Commissioner of Ludhiana who flouted the

prescribed legal norms and ordered that forty-nine hard core Kukas be blown

away by guns. Subsequently sixteen more Kukas were shot in the same manner. The

British wanted to exonerate Waryam Singh, a short statured Kuka prisoner, as he

could not reach up to the mouth of the cannon. But legend has it that he

mounted a pile of bricks and expressed his desire to be shot.

After this heinous act, Kuka headquarters at village Bhaini (district Ludhiana) were raided. Baba Ram Singh was deported to Burma where he died in 1885. Meanwhile, Gurcharan Singh Virk and Bishen Singh Arora, two Kuka leaders, relying on Sau Sakhi’s prediction about the British withdrawal from India in the eighties of the 19th century, tried to get Russian support and even involve Maharaja Duleep Singh (1838-1893), youngest son of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, who had been exiled to Britain in 1854. But they failed in their mission.

Social Reformation

The socio-religious reform movements of the 19th century were oriented towards reforming and rejuvenating the Indian society so that it could cope with the new challenges of the colonial rule. The Arya Samaj, founded by Swami Dayananda (Bombay-1875 and Lahore-1877) restored the confidence of the people in their cultural heritage which is rooted in the Vedas, and generated a form of combative nationalism. In the Satyarth Prakash, Swami Dayananda pleaded for national unity, laid stress on swadeshi and swaraj (self-rule), and delineated the causes of the country’s downfall as illiteracy, ignorance, slavery and indolence. His much propagated view that self-government, even in its worst form, was better than the best foreign government, provided impetus to the growing national consciousness among the people.

The

Arya Samaj produced many leaders of national eminence like Lala Lajpat Rai

(1865-1928), Swami Shraddhananda (1856-1926), Mahatma Hansraj (1864-1938), and

Sripad Damodar Satavalekar (1867-1968) among others. Among the prominent Arya

Samajis who waged a relentless struggle against British imperialism from

foreign lands were Shyamji Krishan Verma (1857-1930), Lala Hardayal (1884-

1939) and Bhai Parmanand (1874-1947).

Punjab and Indian National Congress

Punjab’s association with the Indian National Congress dates back to 1885 - the year the party was founded. Two delegates from Ambala and Lahore participated in its proceedings. Lala Lajpat Rai attended the fourth session of the Congress at Allahabad and impressed everyone with his oratorical skill and political sagacity. He was given the honour of vindicating the resolution which favoured the expansion of Central and Provincial Councils.

In the following year again at the Bombay session, he supported the resolution for an increased representation to Indians in the legislative councils. He took part in the Lahore sessions of the Congress in 1893 and 1900, but felt appalled at the political mendicancy of “holiday patriots’’ who went “where tea and tiffin were ready”; who indulged in “plausibly worded platitudes, and finally ended up muttering “three times, three cheers for Her Majesty the Queen”.

Lal-Bal-Pal Gwalior.

Lal-Bal-Pal Gwalior.

Thereafter,

he was counted among the top extremist leaders of his time along with Bal

Gangadhar Tilak (1856-1920) and Bipin Chander Pal (1858-1932). He was called

upon to preside over the special session of the Congress held at Calcutta after

the Jallianwala Bagh massacre in 1919. While leading a demonstration against

the all-white Simon Commission, he was brutally lathi-charged, which proved

fatal.

Rajkumari Amrit Kaur

Rajkumari Amrit Kaur

Women’s Participation

The

first lady delegate from Punjab to attend the annual session of the Congress

was Miss Jessie Royce, a medical specialist of Ambala, who made her presence

felt in Bombay in 1890. Another Punjabi lady of consequence was Rajkumari Amrit

Kaur (1889-1964) who entered national politics under the guidance of Gopal

Krishna Gokhale, and later served as Secretary to Mahatma Gandhi for sixteen

years. Although a galaxy of Punjabi women are known for their participation in

freedom struggle, one rarely finds their name in the list of Congress delegates

in the pre-Gandhian period.

Agrarian Unrest

The

beginning of the 20th century witnessed agrarian unrest in Punjab which was

fuelled by inflationary trends, rising prices, famine, plague, oppression of

the peasantry, exploitation of rural resources by administration, the

Colonization Act, increase in land tax and water rates in the canal irrigated

areas, and the Land Alienation Act (1900) Amendment bill (1907) which

restricted agriculturists to sell land without government permission.

S.

Denzil Ibbetson (1847-1908), who became Lt. Governor of Punjab in 1905, saw in

these developments the forebodings of another revolt. Such was the tempo of

agitation that its two main leaders - Lala Lajpat Rai and S. Ajit Singh were

deported to Mandalay on June 2, 1907 under regulation 3 of 1883. Amidst strong

protests, they were released after about six months. The Colonisation Bill

(passed in 1906) was finally repealed at the intervention of Lord Kitchener

(1850-1916).

When

the swadeshi and boycott movement in Bengal was losing its verve towards the

second half of 1907, disturbances in Punjab provided the much-needed moral

support to its leaders. Two years later, a young Punjabi student, Madan Lal Dhingra (1887-1909) who was a member of Abhinav Bharat (a revolutionary society founded by Vinayak Damodar Savarkar and Ganesh Damodar Savarkar in 1904), shot dead Sir William Hutt Curzon Wylie, political aid-de camp to the Secretary of State for India, at the India House, while he was leaving the annual ‘At Home’ function hosted by the Indian Nationalist Association at the Imperial Institute, London. After a summary trial he was put to the gallows on August 17, 1909.

Ghadar Party

The

establishment of the Ghadar Party marked the convergence of revolutionary

activities aimed at overthrowing the British rule by way of force. Founded on

April 21, 1913 at Astoria (Oregon) through the efforts of Lala Hardayal (1884-

1939), Baba Sohan Singh Bhakna (1870-1968), Bhai Harnam Singh Tundilat

(1884-1962), Baba Jawala Singh (d.1938), Bhai Parmanand (1874-1947),

Barkatullah (d.1928) and others, the party made Yugantar Ashram (San Francisco,

California), its headquarters.

It

started a revolutionary weekly journal, Ghadar, and established branches all

along the U.S. coast and the Far East. The outbreak of World War I and the

Komagata Maru incident provided a much needed thrust to the Party to proclaim

war on the British, on February 21, 1915. The date was advanced to February 19,

but the plan leaked out, and most of the leaders and prime suspects were

nabbed. They were summarily tried in Lahore - 42

ghadarites were sentenced to death (these included among others, Kartar

Singh Sarabha, whose sacrifice inspired Bhagat Singh); 114 were awarded life

imprisonment and 93 long-term imprisonment.

The

Ghadar movement failed due to lack of proper organisation, and apathy of people

towards nevertheless succeeded in adding to anti-British sentiments which

subsequently led to the formation of Hindustan Socialist Republican Association

(also called Hindustan Socialist Republican Army (established by Chandrasekhar

Azad at Kanpur in 1923) and Naujawan Bharat Sabha, Lahore (established by Bhagat

Singh in 1926). Some of the surviving ghadarites, later became active in Kirti

Kisan Party, Communist Party, trade unions and peasant movements.

Jallianwala Bagh Memorial

Jallianwala Bagh Memorial

Jallianwala Bagh Massacre

The

Anti-Rowlatt Act agitation in Punjab was marked by hartals, demonstrations and

other public protests, the arrest of Dr Saifuddin Kitchlew (1888-1963) and Dr Satyapal

(1885-1954) in Amritsar, as also that of Mahatma Gandhi, near Palwal (Haryana),

when he was on his way to Punjab. All this culminated in the Jallianwala Bagh

massacre at Amritsar on April 13, 1919.

An unarmed crowd of innocent civilians was fired upon by General Reginald Harry Edward Dyer, till all 1650 rounds of ammunition were expended. This left 379 persons dead and 1200 wounded, according to an official report. The Congress Enquiry Committee concluded that even the figure of a thousand persons killed would not be an exaggerated calculation. This was followed by the imposition of martial law, public flogging in Lahore, Gujranwala, Kasur and other places, and many other stringent measures. The Jallianwala Bagh incident exposed Great Britain’s true intention – ‘to rule India not only by force but also by bloodshed’.

Martyrs Well, Jallianwala Bagh.

Martyrs Well, Jallianwala Bagh.

Henceforth,

Indian national movement acquired a mass character under the leadership of

Mahatma Gandhi. He introduced Satyagraha - a new technique of political action

based on the principle of truth and nonviolence - to shake the edifice of the

British Empire.

Later,

S. Udham Singh (1899-1940) avenged the Amritsar carnage by shooting down Sir Michael Francis O’ Dwyer (who was Lieutenant Governor of Punjab at the time of incident), in the Caxton Hall, London, on March 13, 1940. He was convicted of murder and sentenced to death.

Akali Morchas

The Akali Morchas form an inspiring saga of the freedom struggle in Punjab. Fired by the spirit of ‘do or die’, the Akalis stuck to their noble cause and sacrificed their lives without a groan on their lips. The Toshakhana Key’s affair coincided with the Non-Cooperation movement (1920-22) of Mahatma Gandhi, and received Congress support. When the British government surrendered the keys of the treasury of the Golden Temple, Amritsar, on January 5, 1922, Mahatma Gandhi sent a telegram to Baba Kharak Singh, president of S.G.P.C. which read: ‘First battle for India’s freedom won. Congratulations.’

During

the Akali agitation in Nabha which was launched for the restoration of the

illegally deposed Maharaja, Ripudaman Singh (1883-1942), the Congress sent

Jawaharlal Nehru, A. T. Gidwani and K. Santhanam, as observers. But they were

arrested for violating prohibitory orders, before they could reach their

destination.

Although

the Akalis did not succeed in their mission, they were able to goad the people

of princely states of Nabha, Jind, Kapurthala, Faridkot, Malerkotla, Kalsia and

Malagarh to carry on struggle against social and political oppression, economic

exploitation and the undemocratic rule of the princely states. With the

formation of Riyasti Praja Mandal in 1928, the movement got an institutional

base. The dynamic leadership of Sewa Singh Thikriwala (1882-1935) and the

support of Congress provided it with the much needed vigour to work for the

curtailment of privy purses, grant of civil liberties, democratisation of

administration, freedom of press and abolition of inhuman laws. The Praja

Mandal gave ample proof of its nationalistic leanings in 1935 when there was a

proposal for an All India Federation, and again in 1942 when it supported the

Quit India movement launched by Mahatma Gandhi on August 9, 1942.

Babbar Akalis

With the passing of the Gurdwara Act on July 9, 1925 which entrusted the legal control of all historic Sikh shrines with Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (S.G.P.C.) the Akali movement came to an end. However, a parallel movement of Sikh ‘desperadoes’ known as Babbar Akalis continued to feed the flame of liberty with their blood till they were extinguished themselves. Although the movement was short-lived and remained confined to Jalandhar and Hoshiarpur, the dare-devil acts of the Babbars are still remembered.

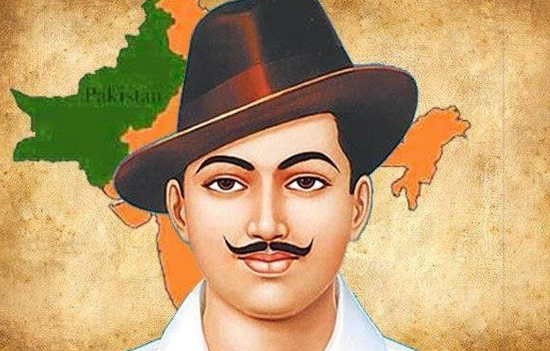

Bhagat Singh

Sardar

Bhagat Singh (1907- 1931), along with his associates, avenged

the death of Lala Lajpat Rai, by killing J.P. Saunders, a police

officer, in Lahore on December 17, 1928. Along with Batukeshwar Dutt

(1910-1965), he threw non-lethal bombs in the Central Legislative Assembly, and

voluntarily offered himself for arrest to highlight the nationalist cause.

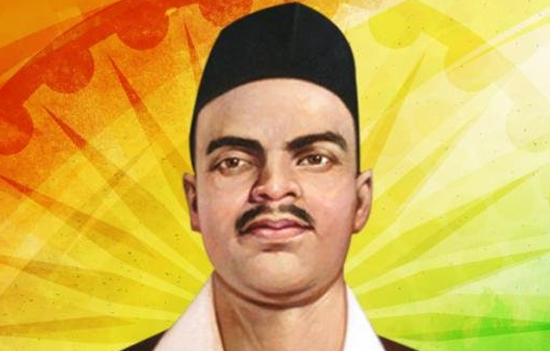

Rajguru was from Maharashtra.

Rajguru was from Maharashtra.

Bhagat

Singh, Shivram Hari Rajguru (1903-31) and Sukhdev (1907-31) were tried in the Lahore

Conspiracy case, and hanged surreptitiously on the night of March 23, 1931.

Their mortal remains were burnt on the banks of Sutlej River to ward off any

public disturbance. The trial of Bhagat Singh and of Ram Prasad Bismil (in

Kakori case,1925), inspired Hari Kishan (1908-31), a Punjabi boy, to attempt to kill Sir Governor of Punjab, when he was to preside over the Punjab University Convocation at Lahore on December 23, 1930. The attempt proved abortive and Hari Kishan was sentenced to death after a flimsy trial. His father, Lala Gurdas Mal Talwar, was involved in more than fourteen legal cases. He breathed his last less than a month after the execution of his son, in Col. Hey’s Court on July 6, 1931.

Gandhian Movements

Punjab’s participation in the three major Gandhian movements of 1920, 1930 and 1942 was no less significant. The Non-Cooperation Movement started on a low note but gained momentum with the visit of Mahatma Gandhi to Punjab. As the movement coalesced with Khilafat movement (1919-24) and Gurudwara Reform movement, it received support from both Muslims and Sikhs. The Central Sikh League which came into being on March 30, 1919, helped to sustain the movement under the leadership of Baba Kharak Singh (1867-1963). The withdrawal of Non Co-operation Movement after the violent incident at Chauri.

Chaura

in Gorakhpur district of U.P., disappointed many in Punjab including Lala

Lajpat Rai who, for some time, joined the Swaraj Party of C.R. Das.

Subsequent Developments

Political developments like the failure of Dyarchy in the provinces (established after Montague Chelmsford reforms), non-representation of Indians in the Simon Commission, the vagueness of Lord Irwin’s declaration of October 1929, the Complete independence resolution of the Indian National Congress at Lahore, and the unfurling of the national flag on the banks of Ravi at the midnight of December 31, 1929, formed the backdrop to the Civil Disobediences Movement of 1930, which began with the Salt march led by Mahatma Gandhi from his Sabarmati Ashram to Dandi.

The

Working Committee of the Congress for 1930 had two leaders from Punjab - Dr

Satya Pal and Sardul Singh Caveesher who worked hard to make the movement

successful. The call for Independence Day Celebrations on January 26, 1930 was

well received in Punjab.

During the World War II, when the British declared India as a belligerent country without consulting the representatives of people, the Congress resigned from ministries in the provinces (formed after the election of 1937). Inadequacy of Lord Linlithgow’s August offer of August 7, 1940, led the Congress to start individual satyagraha (Oct 18). It started on a low note in Punjab but gained momentum soon after. The failure of Cripps Mission led the Congress to start Quit India Movement, also known as August Revolt. But before the movement could take off, Congress leaders including Mahatma Gandhi were arrested. This led to protests, demonstrations and sporadic acts of violence in Punjab as in other parts of India.

Final Phase

The final phase of freedom struggle saw the failure of Gandhi-Jinnah talks (September 9- 27, 1944), of Wavell Plan (1945) and of Cabinet Mission plan (1946). Gandhi’s call for ‘Quit India’ was vociferously countered by Jinnah’s ‘Divide and Quit’. The communal issue, which had persisted for long, reached the point of no return after the direct action of the Muslim League on July 29, 1946.

The British had to quit India in 1947 due to their weak position after the World War II, growing international sympathy for the Indian cause, Naval Mutiny in Bombay (February 18-23 1946), strike in Royal Indian Air force (1946), and disaffection in the army, the police and the bureaucracy. The Indian National Army of Subhas Chandra Bose which had been created by bringing together the Indian prisoners of war captured by the Japanese in Malaya, Singapore and Burma, was the brainchild of Captain Mohan Singh. Likewise, the heroes of I.N.A. trials — Major General Shah Nawaz, Colonel Gurbaksh Singh Dhillon and Major Prem Kumar Sehgal — were from Punjab.

The advent of Labour government in Britain, the acceptance of Mountbatten’s plan both by the Congress and the Muslim League, and the setting up of a Boundary Commission under the Chairmanship of Sir Cyril Radcliffe, set the stage for Indian Independence Act, 1947. But Punjab (which had been in the forefront of the freedom struggle) had to suffer due to its vivisection and the communal frenzy that followed.

Author Dr Satish K

Kapoor, former British Council Scholar, Principal, Lyallpur Khalsa College, and Registrar, DAV University, is a noted educationist, historian and spiritualist.

To read all articles by author

This article was first published in the Bhavan’s Journal, 15 August 2021 issue. This article is courtesy and copyright Bhavan’s Journal, Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, Mumbai 4000-07. eSamskriti has obtained permission from Bhavan’s Journal to share. Do subscribe to the Bhavan’s Journal – it is very good.

Also read

1.

The

Triveni Sangam of the Independence Movement in Tamil Nadu

2.

VP

Menon the man who saved India

3.

Veer Surendra Sai – Freedom Fighter from Orissa

4.

Life

Story of Sardar Patel

5.

How the INA contributed to India’s Independence

6.

Karnataka Goddess of Courage – Kittur Rani

7.

Did

Ahimsa get India freedom?8