-

This is an

excellent prima on the evolution of Sanatana Dharma. The biggest learning is

that what does not change becomes history in course of time.

Sanatan Dharma (also known as Hinduism) is an eternal

concept, the reason why it has become the longest living religion of the world.

The religion flourished despite having its share of ups and downs in its

cherished and checkered history. In comparison, most religions of yore got

wiped out in the sands of time due to external aggression or internal

anarchism, while others which survived witnessed steady decline/ division in

their follower-base.

It

is an interesting enquiry into the oldest religion to understand its basis and

ability to adapt to changes from within and challenges from

without.

Hinduism

flourished

over the millennia

due to a strong

basis in/ focus on Spirituality, evolution and practice.

Hinduism is spirituality-based:

It is based on the philosophia perennis that Self is the permanent

reality/ bliss (also, its opposite, ignorance (Maya), is the root cause

of apparent reality/ misery). Realization of the Truth, that Divinity is

universal, is a matter of faith and not mere belief, it is a matter of understanding

and not mere fantasy.

Hinduism is evolution-oriented:

It is based on the principle that change is an

inevitable aspect of existence; hence, everything needs to stay relevant

in changing circumstances. Resting content with status-quo in practice or

understanding is not a virtue or purpose of life, but evolving through concepts

and contents of creation sure are. This applies even to God‘s’, as they

are an integral part of creation. God ‘evolution’ is part of religious

evolution.

Hinduism is practice-driven: It is based on the premise that for

religious evolution, living its principles is a way of life. Consequently,

practices and rituals at different stages of life are essential elements for

progress through the cosmic-maze/ individual-mania. Worship rituals, the means

to pray and propitiate Gods, also had major role to play in the evolution of

religion.

Of these, many aspects of

Spirituality and Practice are not the monopoly of Hinduism. In fact, they, or

their equivalents (gospels/ canons), are the hallmark of other religions as

well. What really made Hinduism to stay on and stand out was the religion’s

ability to evolve, a fact and factor missed by dead religions.

Religious

Evolution:

Religious evolution essentially centred on:

- The Worshipped (Gods)

- The Worship (Rituals)

- The Worshippers (Followers)

All Gods despite their differing

denominations, and all rituals despite their disparate descriptions, existed in

some form or other. What really happened was fusion of cultures, with followers

appreciating/ accommodating/ assimilating the best parts/ practices of the

other. These qualities turned out to be Hinduism’s saviour during turbulent

years of history, when armed missions and articulate missionaries made repeated

attempts to eclipse it.

1. The Worshipped (Objects-of-Worship):

For Hindus, God is the central theme

of life. But god is not a hard-headed belief, but a broad-minded understanding.

This is confirmed by the marked difference between the Gods the

distant ancestors worshipped and the current generations worship, and that by

itself is a proof that even with respect to Gods we are receptive/

adaptive to changes, a phenomenon unthinkable in other religions.

How did the

Objects-of-worship evolve?

Different

periods of history had different sets of Gods:

The primeval objects-of-worship were the Tutelary Deities/ Vedic Gods.

The medieval objects-of-worship were the Puranic

Gods/ Avatars.

The coeval objects-of-worship are a medley of Gods

and God-men.

The Primeval Gods:

Vedic Gods: They were 33 in number, with no hierarchy (12 Adityas, 11 Rudras, 8 Vasus, Indra and Prajapathi). They were representative of the forces behind the macrocosmic and microcosmic existence. As the Gods were defined by Scriptures, it was a closed-end tradition, i.e. a follower couldn't add or delete a God from the pantheon. Consequently, Vedic worship never

evolved, instead went into decline/ oblivion.

Tutelary Deities: They are the

Gods native to a particular region/ clan, their antiquity paralleling

or even preceding the Vedic ones. Known as Village

Deities (Gram Devata), they were worshipped by a community/ native population from time immemorial. One remarkable aspect of such God-worship was that, despite any amount of advance/ changes in their trade or traditions, the followers' faith never wavered or weakened.

These deities were quite 'earthly' with no fixed pattern in their forms, or purpose in their functions. Anything could be deified by anybody, though some figures (especially the Shakti/ Siva equivalents) were more prevalent/ predominant than others.

Adivasis of Bastar bringing their Kul Devata during Bastar Dussehra, Jagdalpur.

Adivasis of Bastar bringing their Kul Devata during Bastar Dussehra, Jagdalpur.

The natives had three sets of Gods: Clan/ Community Deity (Kul

Devata) (a female or male deity corresponding to Parvati/ Siva), Guardian

Deity (corresponding to Shiva’s sons, Iyappan/ Karthikeya) and Subordinate

deities (corresponding to Ganas of Shiva).

Female deity was

the equivalent of Goddess Parvathi in Vedic worship. She was considered the

fertility goddess who in Her benevolent form bestowed prosperity and knowledge,

and in Her angry form caused pox and similar ailments. No wonder Shakta

goddesses were revered as well as feared.

Every community

had a guardian deity, which was invariably a male deity (in the Dravidian

hinterland it was called Ayyanar). The Vedic people considered Him more

as a son of Shiva.

The temples of main female/

male gods were invariably in the middle of the community settlements, whereas

that of the male guardian deity was always at the outskirts of it.

Since

there were no regulations for defining or identifying Gods, it was an open-end

tradition, i.e. a worshipper/ community could add/ avoid a God from the

pantheon at will. Tutelary gods evolved over the millennia,

notwithstanding cultural and racial prejudices.

The Medieval Gods:

Puranic Gods: They were the central figures of

adulation in the Puranas. The Puranic Gods were many in number,

with well-defined hierarchy. Ishwars, especially Vishnu/ Shiva

were regarded as the foremost, in importance and power, followed

by Sarasvati/ Laxmi/ Parvati (Devis),

and Ganesh/ Surya/ Kartikeya. Further down the Celestial class, there were Devas, Gandharvas,

Apsaras, Kinnaras, Kimpurushas, Yakshas,

Siddhas, Charanas, Vidyadharas, apart from certain Asuric

Gods like Varuna, Bali et al.

Avatars: They were the

central figures of adulation in the Itihasas (Ramayana, Mahabharata and Shrimad

Bhagavatam). Lord Vishnu’s incarnations were the most celebrated, especially

Ram and Krishna Avatars. Their

elevation and adulation planted the seeds of Bhakti Movement, whose

after-effects are sweeping the different corners of Indian landscape even to

this date.

The Coeval Gods:

Gods & God-men: They are an

inter-mix, sometimes an incongruous-mix of above traditions. Apart from

the Gods, the mix included Vedic saints (like Sage Agastya), Itihasa

characters (like Hanuman), self-realized souls ((like Ramakrishna Paramahansa,

Ramana Maharishi), protagonists of Bhakti movement (the 63-Saivaite Nayanmars/

12 Vaishnavaite Alvars, Mirabai, Tulsidas) and holy-men (like Sai Baba). Many

modern-day (self-proclaimed) cult-leaders also staked claim for the exalted

state, though only a few made the grade!

2. The Worship (Rituals):

Most followers ignore or are

ignorant of the lofty truths in the well-meaning scriptures or well-articulated

sermons. It is the rituals which appeals and attracts the imagination of the

individual as he becomes a participant and not a mere spectator.

Also, esoteric rituals which needed

elaborate engagements or educated elite to execute, or that which let a

more-advantaged group dominate over a lesser-privileged one, or which excluded

main-stream participation withered.

Rituals which encouraged flexible/

egalitarian approach, or which were open to changes survived the odds, while

those which adopted a rigid/ elite attitude

collapsed like a pack of cards.

How did the modes-of-worship evolve?

Shrauta tradition:

It is the tradition based on Shrutis

(Vedas). References to very elaborate rituals, mostly Yagnas (Yaga and

Homam) could be found in the Upasana Kanda of the Vedas. It

compulsorily required an officiating priest, Ritvij. Corresponding to

the Vedic hymns recited, they were called Hota (Rig), Adhvaryu

(Yajur), Udgata (Sama) and Brahma (Atharva). Fire (Agni)

was an essential aspect of rituals, as it was He who was deemed to carry the

essence of offerings to higher regions/ Gods. There was always an expectation

preceding every offering.

Tutelar tradition: While Shrauta tradition was ritualistic (demanding more of

‘head’), tutelary God worship was rustic (demanding more of ‘heart’). Hence,

despite their customs being derided and denigrated by the Vedic protagonists,

they proved more versatile. Rituals were simple with no need for sophisticated Tantram

or Mantram. Offerings to God were mostly flowers, plant items or cooked

food. Cooked offerings to the subordinate-gods sometimes included even

non-vegetarian fare. That meant that there was no dichotomy between their daily

routine and god worship, or hypocrisy between their thoughts and practices.

Though Shrauta tradition is extinct, tutelary mode of worship is still

extant.

Smarta tradition: This tradition revolved around Pancayatana-puja (five

shrine worship) with focus on Shiva (Saiva tradition), Vishnu (Vaishnava

tradition), Shakti (Sakta tradition), Ganesh (Ganapatya tradition),

Surya (Saura tradition). In some places, Kartikeya (Kaumara tradition)

is also added to the pantheon, in which case it is called Shanmata

tradition.

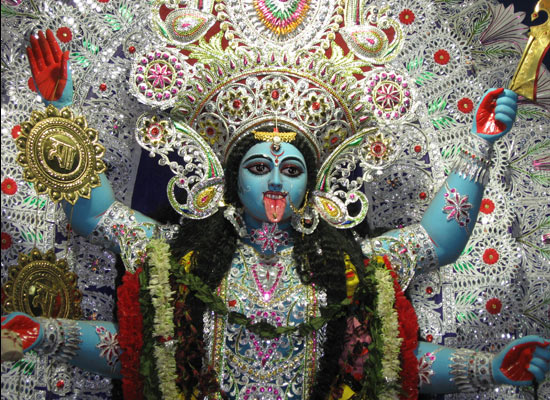

Shakta tradition was the worship

of Shakti, probably the most ancient form of worship. The goddess was

worshipped in a friendly form (fertility goddess) and a fearful form (Kali). Tantric cult and Shakta tradition are closely

related.

Ma Kali.

Ma Kali.

Saiva tradition of Shiva worship

transcended even the Vedic period. He was worshipped in many names (Shankar as

the destroyer-deity and Maheshwar as the Purusha-aspect of Brahman) and forms

(mostly in abstract form like Lingam, and occasionally in tangible form like

Nataraja). Shaivism had different schools – Saiva Siddhanta, Vira

Shaivism, Kashmiri Shaivism, Natha Shaivism, etc.

Vaishnava tradition was the worship

of Vishnu, mostly as the god-of-prosperity (Lord Venkateshwara) amongst a

select group of worshippers, while His incarnations (Avatars), Ram and Krishna were

more and immensely popular across a wide spectrum of followers. Ram and his

consort, Sita and his foremost devotee, Hanuman, and Krishna are the central

figures in two of the longest epics of Hinduism. Radha, Krishna’s playmate of childhood,

but considered more of his soul-mate by his devotees, is not mentioned in the

epics or even in Srimad Bhagavatham. She and

her eternal love for Krishna was probably the product of Bhakti

movement, and her love symbolized the ultimate form of devotion.

Poet Jaydeva in 12th century and Acharya Nimbarka in

13th century immortalized their devotional-love.

Vaishnavism had

four different traditions (Sampradayas) – Brahma Sampradaya

(Madhavacharya – Vyasakutas & Dasakutas), Sri Sampradaya

(Ramanuja – Vadagalai & Thengalai), Rudra Sampradaya

(Vallabhacharya), Kumaras Sampradaya (Nimbarka).

Ganpatya tradition worshipped Ganapati as the central

deity, and was the favorite of almost all Hindus, despite their Advaita or Dwaita affiliations. He is

worshipped before commencing any endeavor as the harbinger of luck and remover

of obstacles in their secular/ spiritual pursuits.

Saura tradition was the worship of Surya, which had a

place of pride in the Vedic period as well. He seamlessly found a slot in the Smarta tradition too, as He was

the only prominent divinity visible in physical realm. In fact, the most

sacred/ secret/ potent mantra of Hinduism, Gayatri Mantra, is a hymn in eulogy and entreaty of the

Surya devata.

Kaumara tradition was the worship of Skanda (Murugan/

Kartikeya), the commander-in-chief of Gods. He was more popular in the southern

parts.

The Smarta system

of worship probably existed for long, but found rightful space and

importance in/ during/ post Bhakti movement which swept India from the 8th

century, more particularly from the 11th-13th centuries.

The most common mode of worship under the Smarta traditions is Sodasopachara,

the 16-step rituals. The more elaborate pujas needed the services of

an Aagama priest, but the lesser ones were done by a

householder himself. There may or may not be an expectation for doing the puja,

but devotion was always an underlying and unifying thread.

Krishna Worship, Ras Mahotsav Majuli, Assam 2018

Krishna Worship, Ras Mahotsav Majuli, Assam 2018

3. The Worshippers (the followers):

The followers of

the religion are spread over a broad spectrum of background. Defining the paradigms which characterize the followers, and decoding the paradoxes which confuse the observers can be a

daunting task. While the paradigms confirm followers’ social/ cultural/

spiritual similarity, the paradoxes convey their ethnical, geographical and ideological diversity.

The paradigms

which define a follower: A Hindu is defined by not just an explicit belief in

religion, but also an implicit faith in spirituality. It is not just adopting a

time-tested tenet, but also accepting a contrary view-point. It is not just the

freedom to profess chosen path, but also the willingness to embrace changes en

route. It is not just the ability to stay rooted in traditions, but also an

earnestness to evolve to a higher order.

The paradoxes

which confuse an onlooker: Hindus would fight amongst themselves, but not

resort to armed aggression on neighbors. They would advocate supremacy of a

sect’s philosophy over other, but not their religion over others. They would

fast for religious reasons, but feast in

the name of same gods. They would abstain

from intoxicants on auspicious days (Shravan),

but get drunk in the name of the same gods (Shivratri).

They would ensure handsome donations to an advantaged ‘creator’ (God/ temple),

but not to a disadvantaged ‘created’ (down-trodden). They wouldn’t offer their

hands for wishing a stranger, but relish their meals with hands. They would be

extremely fuzzy about personal hygiene, but would be equally reckless about

public cleanliness.

How did the Followers evolve?

The Itihasas

and Puranic era (5th century BCE) followed the Vedic period

(15th-5th century BCE), initially co-existing, later

eclipsing it totally. The Vedic worshippers had a very rigid regimen and

they had no freedom to pursue anything to the contrary. The tutelary deity

worship was more laissez-faire, affording freedom to worshippers.

Due

to the stranglehold of the people from the higher strata, and non-participatory

nature of Vedic worship, there was mass exodus of people, largely from the

lower strata of society.

Enter

now Mahavira. Some claim that Jain religion is much older, perhaps

starting with Rishabha, the great-great-grandson

of Swyambhavu Manu, and ending with the 24th Tirtankara, Mahavira

(around 6th century BCE). Jainism had patrons among the ruling

elite, therefore flourished due to state support.

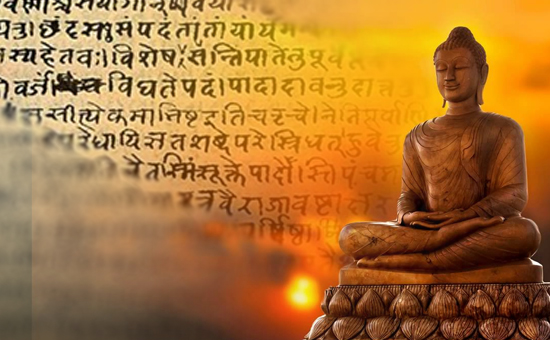

Buddhism

came into existence almost at the same time as Mahavira (6th century

BCE). Buddha’s message was simple and universal. It preached and practiced

egalitarianism with no social stratification. Buddhism had mass following.

With its focus on middle-path (Madhyama Marg), it spread far and wide

very rapidly, even to the far-east countries, where it is a major religion now.

The

rapid spread of Jainism and Buddhism during the centuries preceding and

following Common Era (5th century BCE to 5th century CE),

caused rapid erosion in the ranks and ratings of Hinduism. The turmoil was more

pronounced in the northern parts due to diffused and shuffling political

landscape. Fortunately, south was relatively free of these headwinds and the

tranquil environment spawned a brand of Bhakti movement.

Buddha

Buddha

5th-6th

CE onwards, Saivaite Nayanmars sowed the seeds of Bhakti movement in

south India. But unification of the divergent and distraught Hindus had to wait

for few more centuries, not until Shankaracharya entered the ‘revival-battle’

in the 8th century. Within 32 years of event-filled life, he managed to bring all the drifting and disparate sects of Hinduism with a gospel message that every/ everyone's God was an aspect of ultimate truth, and that any/ every mode of worship was acceptable to god, if performed with love and faith.

Overnight,

Smarta tradition found its bearings. In Smarta system, a follower

became a ‘proximate’ participant, unlike a Yajna, where he was a

‘silent’ spectator! This appealed to masses and Hinduism retraced its lost

glory over the next few centuries. Thus did Shankaracharya bring the ideologically drifting and geographically

spread-out sects back into the folds of mainstream Hinduism almost single-handedly?

Though Vedic ideology

dramatically differed from the local traditions, the Vedic

people were in total sync with the native population. There was a

healthy mixing of different strata of the society.

Veda

Vyasa, for example, was born of Parashara muni and a fisher-woman, Satyavati.

Vyasa’s guru, Acharya Gautama was married to Sharmi, a tribal girl from the

Godhuli village, so was Sukha, Vyasa’s son, to Peevaree, a sister of

the tribal chieftain. Such inter-mingling of people even at the highest level,

facilitated the fusion of cultures then and even much later.

Unity in diversity – where/ how did the traditions

concur/ differ?

In

Vedic God worship (Shrauta

traditions), Idols (Yantram) were

unknown, while Mantram was the major

means to address Gods, with Tantram

(rituals) playing a subsidiary role.

In

Tutelary God worship, Idols (Yantram)

were essential aspect of worship, with Tantram

(Rituals) complementing the worship regimen. Mantram was unknown.

In

Puranic God worship (Smarta

traditions), Aagama Shastras defined

exacting specifications for Yantram

(for Idols and Temples). 16-step-rituals, in full/ part (Tantram) was an essential aspect of worship. Chanting of Mantram, and Bhajans/ Kirtans in its absence (sometimes in addition), completed

the worship protocols.

Gods were more

‘heavenly’ in Shrauta traditions, whereas the Tutelary Gods were more

earthly, that is, the followers could see God in human forms (some people would

get ‘possessed’ by the deities (ritual shaman dance), called ‘Sami Aadis’

in Tamil, literally dance of gods). Communicating with the tutelary gods was

very easy, as the gods (in the form of ‘possessed’ revelers) would talk the

native tongue (an oracle). It was almost impossible in the Vedic tradition, as

the language (Sanskrit) and the intermediaries (Brahmins) acted as barriers to

free communication.

The Puranic

idols were sculpted to exacting specifications, whereas the Tutelary gods were

not as portly, mostly made of mud or in some cases even a simple stone. Temple worship was foreign to Vedic culture,

which believed in Homas and Yagas to invoke/

propitiate Gods.

Smarta tradition is a fusion of cultures; it borrowed the Temple culture of

natives and the worship rituals of Shrauta culture, which appealed to the entire spectrum of Hindu devotees.

Vedic people

never had temples, nor idols for worship. They would erect a place for Yaga-Homa and

destroy it after the puja. Consecration and dismantling the Yajnakund

were part of the rituals. In comparison, tutelary gods always had a place for worship, either within the core settlement or in the near periphery or in the yonder wilderness. The natives didn't have elaborate worship or Samskara rituals. Hence, services of a learned pandit

were not a necessity.

It

was common for community members to perform rituals.

In a fusion of

cultures, and over a period of time, the Smarta tradition accepted the

fixed-place (temple) worship-concept of the natives and the worship rituals of

the Vedic people. Also, most of the native gods were absorbed into the Hindu

pantheon as aspects of Shiva-Parvathi or their descendants.

Family deity (Kul

Devata) was an essential element in native worship. In Smarta

tradition, Personal deity (Ishta Devata) had a prominent and preeminent

position. Shrauta tradition never presented options.

The Smarta

tradition of God-worship was a mid-way point, where a worshipper had the

freedom to choose a God (like natives) from a galaxy of them (like Puranic

gods). Even the worship could be effected with a simple offer of

flower (like natives) to an elaborate set of Upacharas (like Vedic).

At ancient Shiv Mandir

Manikaran, Himachal Pradesh. Known for hot water springs.

At ancient Shiv Mandir

Manikaran, Himachal Pradesh. Known for hot water springs.

Shiva worship is a typical example of the fusion of

cultures:

Amongst Vedic

lore, there was no concept of Destroyer. They worshipped 11 Rudras (the

ferocious ones, probably representing wind/ storm).

Amongst Tutelary

gods also there was no concept of Destroyer either. There was a female goddess

and her consort was Ayyan (in south India).

Shiva (meaning

the auspicious, representing Destroyer) was a later addition to the Puranic

pantheon.

When Bhakti

movement swept through the Hindu landscape, the Vedic Rudras and the tutelary

‘Ayyan’ got ‘merged’ with Shiva. True to the saying, ‘all is well that ends

well’, the merger was seamless and successful.

Bhakti movement was a blessing:

The latter day Dvaita

practitioners literally usurped/ hijacked the Saivaite-initiated Bhakti-oriented

Smarta traditions, but that only added muscle and momentum to the

renaissance rather than undermining the original premises of Advaita

practitioners.

The

Bhakti movement, though it remarkably contributed to the arresting of

the spread of Buddhism, yet, produced its share of problems, with Advaita

and Dvaita followers fighting for supremacy.

Once again,

tutelary deities were called in to subdue frayed tempers. A guardian deity of

Dravidian hinterland, Ayyanar, came handy for resolving the Saiva-Vaishnava dispute. He was

considered as the son of Vishnu (Hari) (Vishnu as Mohini) and Lord Shiva

(Hara). Ayyanar became the famed Hariharaputra, also called Sastha or Aiyappan,

who then became a rage in the sub-continent.

Fortunately,

by the time Mughals came in the 14th-15th century, the reforms and Bhakti

movement had firmly taken root. So deep was the foundation and so strong was the edifice that the fervour or the fatwas

of the new rulers failed to make a dent in the structure and solidarity of

Hindus.

Centuries

later the British attempted to shake their basic faith, but without success.

However, their strategy to break the unity on caste lines met with enormous

success. (Remember, Hindus loathe

to fight external war of aggression, but love to fight internal sects to the

last man).

The

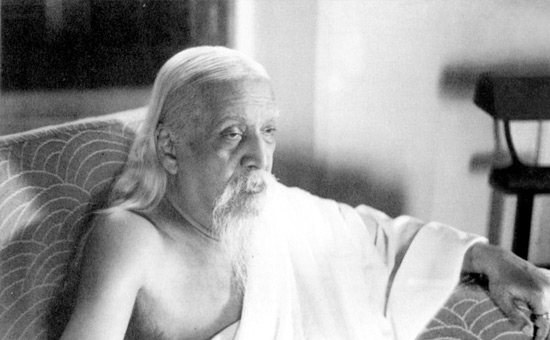

solidarity of the religious milieu became a main plank of launching freedom

movement by some leaders like Tilak, Aurobindo, during British rule.

But the caste-division still continues to haunt the society even now.

Maharshi Aurobindo. Read his writings in India’s

Rebirth to know Bharat.

Maharshi Aurobindo. Read his writings in India’s

Rebirth to know Bharat.

THUS,

Self/ Truth is supreme in Indian Spirituality. It

considers even God as an ‘extension/ symbol’ of

this truth.

Hinduism flourished because it was open to evolution

even with respect to Gods, something unimaginable/ blasphemous in most

religions. Hinduism was not dogmatic even with respect to their Gods; hence, it

had no qualms in adopting different Gods that accommodated people of different

geographical/ ideological background, or that evolved with their aspirations/

understanding.

Unlike evolution of human (thoughts) which takes

place over a few years, and that of human (renaissance) which takes place over

a few decades, and that of humanity over a few centuries,

the god evolution in Hinduism took place over a few thousand years.

Surprisingly, from the orthodox Dravidian heartland,

where Vedic religion played second fiddle to tutelary god-worship, arose the

three pioneering religious reformers of Hinduism, Shankaracharya, Sri Ramanujar

and Madhavacharya, and their historic schools of thoughts, Advaita, Dvaita and

Vishistadvaita.

Surprisingly, it was the upper-caste leaders who

initiated the religious renaissance initially and sustained the Bhakti

movement subsequently.

Surprisingly, it was the principal proponent of Advaita

who seeded the bhakti concept, a distinguishing mark of Dvaita,

as a means to get the drifting masses back in the fold of Hinduism.

OM Namah Shivayah

Author is an Alumnus of BITS, Pilani (MPharm). He worked with some of India’s best MNC Pharma companies. Currently writes articles on Spirituality. One book, Spirituality - A Roadmap is published. The next book, 'Mindfulness - A Roadmap' is ready for publication.