- A century after he first arrived from India the great teacher’s legacy continues to inspire the spiritually minded in America.

I was

a precocious child. My favorite activity with a babysitter was to ask for blank

paper so I could write. Reading fluently before I entered kindergarten, I was

fascinated with Hindu mythology and studied it avidly. After memorizing the

names of all prominent Indian Deities, I collected their murtis, including a

rare statue of Brahma, before I was eight. Alas, this fascination was not to

last.

Other children seldom knew what I was talking about. Seeking acceptance, I became an expert on Disney and Pokemon. Obsessed with trying to be cool like my peers on terms defined by them, I tried hard to fit in. This became a vicious cycle. The harder I tried to fit in, the more difficult and stressed I felt—so I tried even harder, setting unreasonable expectations for myself that led to increased frustration.

I felt intuitively that there was more to life, but I was on a treadmill that wouldn’t stop turning. With the support of many mentors, I slowly got off the treadmill and began a long journey to reconnect with my ancient Hindu roots. It was difficult but, in retrospect, I would not have it any other way.

This article was

first published in Hinduism Today.

In 8th grade, my dad and I travelled to Norway and stayed at the home of Mark Kriger, a former classmate of my father. Before starting his PhD in business at Harvard, Mark had earned a master’s in religion from MIT and had worked closely withHuston Smith, the legendary author of The World’s Religions. Like Smith, Mark spent many years exploring different spiritual traditions, including Vedanta, and had visited Sri Ramana Maharshi’s ashram in Annamalai.

Three years later, Mark visited us in Los Angeles. His visit coincided with my starting 11th grade, a period of heightened anxiety. Mark told me he always went to the Self Realization Fellowship (SRF) Lake Shrine in Pacific Palisades whenever he was in Los Angeles. He invited me to accompany him, and I readily agreed. If Mark had a specific objective in taking me to the serene Lake Shrine, I was oblivious to it. I remained engulfed in my mind’s ongoing mental chatter and gave little attention to the beautiful surroundings.

The

visit to the Lake Shrine must have planted a seed, because twelve years later,

as a graduate of the University of Southern California (USC), I am striving to

deepen my spiritual quest. I have greater commitment to learn and am more

confident in my ability to help others. The memory of my first visit to the

Lake Shrine is etched in my mind, and I think back to the visit, grateful to

Mark for opening my eyes to one of the most impactful gurus of global

spirituality, Paramahansa Yogananda.

The Lake Shrine is one of many SRF centers in Southern California. In 1925, Yogananda established his organization’s headquarters in Mount Washington, a few miles south of my Pasadena home, on a serene hill sheltered from the hustle and bustle of Los Angeles. Once I learned that Yogananda had played a pivotal role in my “backyard,” my lifelong love of geography and deep interest in the Indian diaspora drove me to explore his life and the many SRF temples within a short driving distance.

Home of Paramhansa Yogananda at Mount Washington in LA.

Home of Paramhansa Yogananda at Mount Washington in LA.

Not

far from the Mount Washington SRF headquarters is the Hollywood Temple on

Sunset Boulevard. Built during the 1930s, it is striking in appearance with its

large masjid-like onion-shaped domes. On a stretch of land alongside the

Pacific Ocean in Encinitas, near San Diego, is an SRF temple gifted to

Yogananda in 1937 by James Lynn, a staunch devotee and business tycoon. The

grounds are dotted with greenery, koi ponds, small waterfalls, and benches for

meditation. Each SRF center is an oasis of serenity.

I

reached out to different people to ask about Yogananda. Prasad Kaipa, an old friend of my father’s, combines great insight with a patience and humility that inevitably makes me relax in his presence. Fluent in Sanskrit, Prasad has the rare ability to intertwine ancient Hindu wisdom with modern business advice.

I asked him about Yogananda’s impact on his life.

He began, “I used to work at Apple when Apple was a young company. My uncle in India was a very devoted follower of Kriya Yoga and asked me to bring him SRF books and videos from the US. I had not read or watched any of them. I felt there are so many swamis in India, I do not know whom to follow. But my uncle gave me a copy of Yogananda’s Autobiography of a Yogi and told me to read it as soon as possible. I finished the book in three days, and it put me into a totally different state of mind. On returning to the US, I went to Yosemite and meditated for three days. It brought clarity to what I wanted to do in life, and I quit working at Apple.”

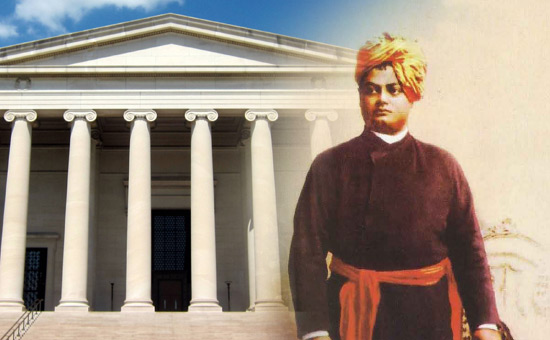

Struck by the transformational impact of Paramahansa Yogananda on people like Prasad and Mark, I read more about him and discovered he was the second Indian guru to visit the United States. The first, Swami Vivekananda, came to Chicago in 1890 to speak at the Parliament of World Religions. Vivekananda questioned Western stereotypes about Indians as backward, heathen snake charmers and described Hinduism as the historical mother of all religions, arguing that Hinduism’s core message of embracing all religions should be universal.

Following his ground breaking speech, Vivekananda started Vedanta Society branches in several major US cities. Prasad Kaipa commented, “Unlike Vivekananda, who founded the Vedanta Society and went back to India, Yogananda stayed in the US and continued teaching. Yogananda helped cement what Vivekananda preached about, by building the infrastructure in the US.”

My

turning point and recommitment to Hinduism began when I left USC and no longer

had a religious social community with which to connect. Reading Autobiography

of a Yogi helped me look inside myself. I began to understand that the

essence of religion and spirituality is to find your own inner peace through

meditation and to contribute to the betterment of society as a whole. I then

realized my mistake in joining a religious community at USC for the expectation

of a social community, a form of outward pleasure, rather than introspection

and self-understanding, which are the foundations of Self-Realization.

Autobiography of a Yogi has had a strong impact on thousands around the world. In the Yogananda documentary, Awake, Beatle George Harrison says, “If I had not read it, I would probably not have a life. I would probably have kicked the bucket or would just be some really horrible person. It gave meaning to life.” It was the only book on Steve Jobs’ iPad, and he re-read it every year. At his memorial service at Stanford University, all attendees received a copy of the book as a last gift from Jobs.

One

of the highlights of my time at USC was getting to know Varun Soni, USC’s Dean of Religious Life and the first Hindu to serve as the religious leader of a major university. I spoke regularly with him about my questions regarding spiritual growth.

Dean Soni explained to me that America’s racism at the time of Yogananda’s visit made his mission even more remarkable. “He brought Indian tradition to the West; we mostly only saw the reverse. Christian missionaries came to India; Indian missionaries did not come to the West.” He added, “This was a time of Asiatic exclusion and racism. Still, this Indian man

introduced all these spiritual thinkers to ancient Indian practices.”

Yogananda arrived in 1920 on the ship The City of Sparta to attend the Seventh Unitarian Congress of Liberals in Boston. His guru, Swami Sri Yukteshwar, had long had a vision that his disciple would someday bridge the gap between Eastern spirituality and Western materialism. To fulfil his guru’s expectations, Yogananda, who had never set foot overseas, travelled to the USA.

Yogananda’s talk in Boston, “Science of Religion,” focused on the very core of what religion is all about. He famously stated, “In the world today, every person, no matter what they are doing, no matter what they are seeking, or their desire, are going for two goals: they want to avoid pain and attain bliss.” Thus, “religion is that practice that brings about permanent avoidance of pain and attainment of bliss.”

The period following World War I was a time of growing religious skepticism and increased materialism. The Awake film describes this period as the “dawn of the atomic age, when physics could shatter your beliefs about the nature of reality.” Soni recalls, “There were all these arguments that science would destroy humanity. Yogananda taught the science of spirituality as a counterbalance to the age of nuclear weapons to save humanity.”

I

interviewed Philip Goldberg, author of American Veda and The Life of Yogananda. He describes how Yogananda considered Los Angeles to be the Banaras of America. He “perceived something in the city’s character that set it apart as a destination for explorers of the soul.” Soni agrees: “The West Coast was already imagined as a place of new beginnings. Since Asians have historically come to the West Coast, people were already conscious of Eastern traditions. Yogananda found the right audience and the right time for the right message.” Something clearly worked, because Yogananda attracted packed audiences wherever he spoke.

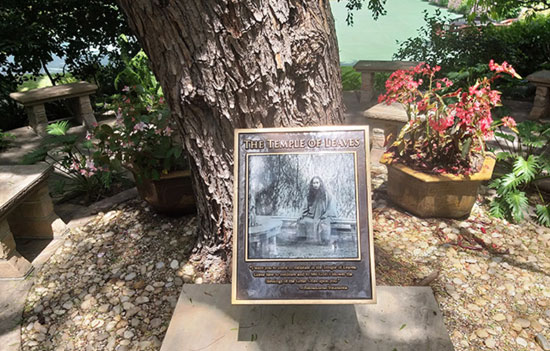

Temple of Leaves, a small garden with benches where Yogananda meditated.

Temple of Leaves, a small garden with benches where Yogananda meditated.

Yogananda’s fundamental principle is the universality

of religion. Remarkably, he introduced Hinduism to the West through the

lens of Jesus.

Soni says, “He understood that when he came to the USA, he would talk to many Christians, and he used Jesus to bridge the East and West and bring people together.” Soni added, “Jesus is like an avatar for some Hindus, he is God coming to Earth in human form to teach us. Thus, Jesus is a bridge between Hinduism and Christianity, which Yogananda understood.” In fact, his lineage continued through a Mormon woman, Dayamata, who led SRF for even longer than Yogananda himself. Kaipa told me, “Yogananda

integrated with local religions much more fluidly than other spiritual gurus, without any conflicts between their religion and his teachings.”

Ravi Sahay was born in a village in Bihar, India and came to the US to pursue his career as an electrical engineer. While looking for a place that would provide his children a broad sense of religion, he discovered the Yogananda Temple in San Diego and immersed himself in Yogananda’s teachings.

Now a retiree, Sahay is an SRF volunteer and resides in a small trailer next to the SRF Hidden Valley Ashram in Escondido. Sahay reflects on how Yogananda tied Vedic teachings with the essence of all world religions: “Human beings are basically designed, wired children of God. Vedic principles say no matter what you do, you will not be happy until you find peace. There are several people who become very rich but are unhappy and commit suicide. Vedic religion says if you do not get it in this life, you will get it in the next life. That is your only path.”

In his book, Science of Religion, Yogananda explains, “Religion consists in the permanent removal of pain and realization of bliss, or God. If we understand religion in this way, then its universality becomes obvious.”

The

primary technique Yogananda promoted to help people in the West attain this

goal was kriya yoga. Kaipa told me, “This practice helps you develop humility, inclusiveness, and openness.” To address the growing emphasis on science and physics, Yogananda presented Hinduism as a science.

According to Soni, “He used the language of science to talk about the spiritual practice of kriya yoga, the science of breath, energy and consciousness. You did not have to have faith and believe. You had the practices so you could test these hypotheses as a scientific practice.” Sahay adds, “The more ego-driven we are, the less spiritual we are. Spirituality is about letting our ego hang loose. Spirituality is realizing that our ego is not working in our best interest or our community’s. There is no other good definition.”

My

friend Gyan Alexander is a young man in his 30s. Gyan has practiced Yogananda’s kriya yoga throughout his life, and it was his source of strength when his closest childhood friend committed suicide. Gyan says, “Practicing kriya yoga has helped me navigate the anxieties and challenges life throws at me. Sitting still and finding inner stillness has helped me separate who I am from the problems I face.” He adds, “We are constantly victims of the feeling of not having enough. Meditation at its best helps you realize that you are enough. In my unpredictable career as a scriptwriter, there is something very secure about this practice that has definitely helped me logically and creatively.”

Swami Vivekananda brought Vedanta to the West.

Swami Vivekananda brought Vedanta to the West.

Gyan’s mother, Kamala, is a convert from Sikhism to SRF. She was born and raised in Yuba City, Northern California, where her family owned a farm. She was a nurse in Southern California when she met her future husband, Ranya Alexander, an African-American emergency-room doctor. They chose the Lake Shrine as the venue for their wedding. Ranya’s SRF practice and the serenity of the Lake Shrine motivated Kamala to wholeheartedly accept SRF. Although her devout Sikh family opposed her marriage and her adoption of SRF, she remained steadfast in her commitment.

She reflected, “Giving up Sikhism helped me

understand my birth faith even more. It taught me the essence of what Nanakji and the other Sikh gurus did. Being brought up in the West, understanding the Guru Granth Sahib was not easy. Yogananda has volumes written with his own hand, so it satisfies the intellect. He gives you techniques of meditation that can lead to your own experience of the Divine. They are scientific techniques; that helps.”

Gyan, an SRF follower since birth, recalls his experience volunteering at the Mount Washington headquarters: “You notice how the monks take care of the grounds with so much attention and quiet, contemplative joy. When they talk, it is very exact, no extra noise. They do a great job cultivating the place. Watching pilgrims arrive on the bus, you feel you are in a slice of heaven.” Gyan sees SRF as a church of all religions. He says, “It has made me comfortable in navigating other houses of worship. I can find universal messages that resonate with me, whether it is people who practice other faiths, or even atheists.”

In Awake, Varun Soni says, “Yogananda provided us a vocabulary to talk about the spirit. It gets away from dogma, doctrine and ritual. Whatever tradition you are part of, Yogananda charted a path inward that connected

you with your own divinity.” The Science of Religion further explains, “The proof of existence of God lies in ourselves and our inner experience. It is in bliss consciousness that we realize Him. There can be no other direct proof of His existence. It is in His bliss that our spiritual hopes and aspirations find fulfillment, our devotion and love find an object.”

In reflecting on Yogananda’s legacy, Soni said, “The one thing that is most associated with Indians in the US is yoga. Today, yoga is something 15 million Americans do. Although most of them do it in the context of fitness, Yogananda brought it as a spiritual practice. Yogananda helped bring it here.”

Today, twelve years since I first visited the Lake Shrine, oblivious at that time to Yogananda’s teachings, I am applying to graduate programs in Clinical Social Work. I hope to use the fundamentals of Yogananda’s teachings both to inspire individuals to be at peace with themselves, and to strive to make the world a better place. When I visit Lake Shrine today, its unique tranquillity lingers with me. Paramahansa Yogananda’s Autobiography of a Yogi is a source of wisdom that I return to time and again.

Reflecting on Yogananda’s teachings, I realize my parents never brought me up to follow only one black-and-white train of thought. They always encouraged me to find my own inner purpose and direction. Yogananda combines the best of the East and the best of the West, showing that spiritual principles and rational scientific analysis are synergistic rather than exclusionary.

Reading Yogananda’s Autobiography has helped me find my purpose. Learning from the many people who have preceded me on this path has strengthened my commitment. In the midst of today’s divisive world, there is much to heed from Yogananda’s principles of oneness, and I consider myself a very grateful beneficiary of the traditions inspired by Paramahansa Yogananda.