- For the first time in many decades, a hill fort in the Sahyadris faced a military challenge from an external power. This time, not from the Mughals but the British at Malanggad near Kalyan.

- The writer is the author of a recently published book 'Battles of the Maratha Empire.'

A hill fort

besieged. A thin garrison holding out against the odds. Repeated attempts to

raise the siege from without. The importance of supplies, routes, intelligence,

strategy, reconnaissance.

No this scene isn’t from a Mughal – Maratha battle from the seventeenth century but the East India Company facing off against Nana Phadnis at the close of the eighteenth! The hill fort in question here is Malanggad, near Kalyan.

The British East

India Company opened hostilities against the Marathas in 1774, by attacking

Thane. Thus commenced the First Anglo Maratha War.

Their aim was to

install Raghunathrao as a puppet at Pune and effectively control the Maratha Empire.

But in 1779, a debacle at Wadgaon (covered in Battles of the Maratha Empire)

ended that ill planned dream.

Another battle

took place, this time at Malanggad near Kalyan, the following year. And like at

Wadgaon, it too marked a Maratha victory over the

British.

The reason for the Malanggad conflict were slightly different. Having received a bloody nose at Wadgaon, the EIC wanted to make sure their prize possession of Mumbai (by this I mean the British possessions in south Mumbai – roughly Colaba to Sion, the remaining part Sashthi or Salsette Island was with the Marathas) did not get threatened by Nana Phadnis.

This in turn meant

controlling the fort of Vasai to the north of Mumbai, which again the Marathas

had obtained from the Portuguese in 1739 (the Vasai campaign, covered in

Battles of the Maratha Empire).

But capturing Vasai wasn’t enough, what was needed was control over Kalyan – a principal port and town in medieval Maharashtra. Even today, just the roads and rail routes leading to, from and via Kalyan make its importance apparent. From the north, the route via Kasur ghat passed to Kalyan. From the east, a route turned from Khopoli and headed to Kalyan (old highway and railway route now). Even from Panvel, a route led to Kalyan via the Taloja route. Kalyan itself was a port city, thus it could be serviced from the west via the sea too.

Source: Capt James Barton's 12 views of hill forts in Western Ghats, 1820.

Source: Capt James Barton's 12 views of hill forts in Western Ghats, 1820.

Guarding

the town of Kalyan was Malanggad - a square shaped massif a short distance

away to the south. The EIC decided to begin their Vasai campaign by

capturing this hill fort.

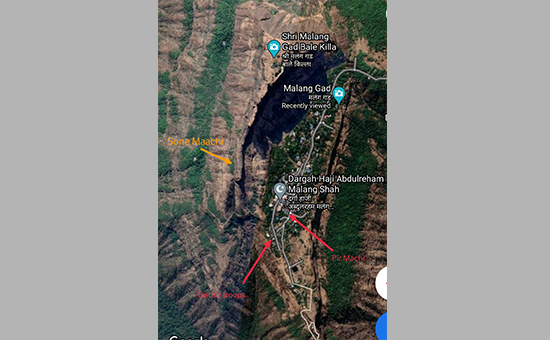

One can spot this square shaped hill to the north just as one leaves Belapur on the Mumbai – Pune highway. The fort itself is rather isolated and its natural defenses become readily apparent as one treks to its summit. It is known by various names – Shri Malanggad, Cathedral Rock and Haji Malang (after the dargah on the fort). It commands an excellent view of the north Mumbai region as also routes all the way to Panvel. Consisting of three parts – the Pir Machi (part where dargah is situated), the Sone Machi (a trunk like part) and the Citadel or Ballekilla. The Sone Machi being situated at the top of a perpendicular wall of basalt, the natural defences of the fort are more than apparent. The nearby hill of Tavli doesn’t have a flat summit and is in fact quite difficult to scale. Malanggad itself is a part of a series of hills, which leads right up to Peb and Matheran - thus making a complete encirclement difficult.

Credits Google Maps.

Credits Google Maps.

The British aimed to capture this fort and then turn their attention to Vasai. With the routes leading to Mumbai from Pune blockaded and watched over, and little help expected from Gujarat , the capture of Vasai would make the ‘ring’ around Mumbai complete. It would also mean that the Maratha island of Salsette, which they had obtained from the Portuguese would fall into British hands.

British

moves

The British knew

that an important route to Kalyan was via Panvel and Thane. Accordingly, Capt.

Campbell captured Parsik hill near Thane on the 12th of April, 1780.

On the same day, at the other end of Mumbai - the fort of Belapur was taken by

Capt Lendrum. This fort was situated at a most opportune location and

essentially guarded Panvel creek and the town.

With the fort

having fallen, the responsibility for defending Panvel fell on Naro Vishnu and

his Gardi musketeers. But outnumbered and with the threat of encirclement

looming, he evacuated Panvel and headed for Kalyan - thus the place fell to

Capt Lendrum. This being an important Maratha outpost, the British wanted to

nip any help which may reach Kalyan by the Panvel - Taloja - Kalyan road in the

bud itself. The EIC then moved on to Taloja, and having established a guard

post there, proceeded to evict the Maratha garrison at Thakurli.

By the beginning

of May 1780, Capt Campbell had managed to reach Kalyan, which although defended

stoically by its Mamledar - Karlekar, fell to the British after five - six

hours of heavy bombardment. Another attempt was made by Bajipant Joshi and

Sakharam Panse to drive the British out of Kalyan, but was repulsed and driven

back to the village of Neral (near Matheran) Interesting to note, that in this

engagement the Marathas used rockets!

Thus ended the month of May, with the British in control of a swathe of territory from Panvel to Kalyan. But still, the fort of Malanggad remained in Maratha hands. They also held the route leading to it from the forts / hills of Peb and Bhimashankar to the east.

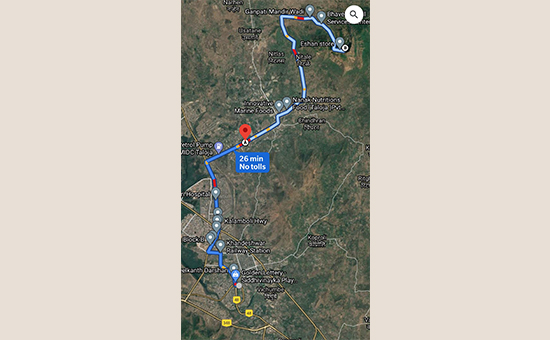

Belapur-Taloja-Malanggad. Credits Google Maps.

Belapur-Taloja-Malanggad. Credits Google Maps.

Siege

of Malanggad

When Kalyan fell,

Malanggad was under the control of Pandurang Sambhaji Ketkar.

The British did

not immediately move towards the fort in the hot months of May and June, but

instead decided on August to attack. Since the time of Chhatrapati Shivaji, the

monsoons had been taken as a time when warfare came to a stalemate in the hills

and forests of the Sahyadris. What with the torrential rain making moving on

the slushy ground extremely difficult and the dense fog making it impossible to

sight anything So, even in 1780 , not

expecting much action , some of the garrison from Malanggad had been granted

leave as had been the practise. The Marathas were left with only three hundred

troops on the larger Pir Machi.

On the 4th

of August 1780, under orders from Major Hopkins, Capt Abbington attacked the

fort and although Pandurang Ketkar fought bravely, the British managed to

capture Pir Machi. This is the Machi on which the dargah is situated. Since the

Marathas were least expecting an attack in the monsoon months merely three

hundred were guarding the fort. Ketkar retreated to the other machi - Sone

machi and decided to make a stand over there. But staying on the narrow Sone

machi was an even tougher task. 175

soldiers left the fort and made their way to Gangadhar Karlekar, the Mamlatdar

of Kalyan. Pandurang Ketkar continued to fight Abbington with his hundred odd

troops and a couple of months of food supply.

Pune

reacts

Nana Phadnavis,

realising the gravity of the situation, decided to send Gangadhar Karlekar,

Kashipant and Anandrao Dhulap to aid Pandurang Ketkar. They proceeded up to

Neral. From here unfortunately, the next fortnight was spent in indecision,

with the result that it was as late as 28th of August that they

finally managed to reach a village called Kharawai near the fort. Prior to this

advance to Kharavai, a few hundred soldiers under the leadership of some lesser

known commanders were sent to Malanggad. The result being that the British

siege was not attacked with the vigour it demanded for nearly a month allowing Abbington

to entrench himself and unfurl the Union Jack on Pir Machi.

He also managed to

get some cannons up the fort to Pir Machi and was busy bombarding the Sone

Machi above it. One spectacular assault was carried out in the first week of

September, but was bravely beaten back.

On the fort was

Pandurang Sambhaji Ketkar and his hundred odd Gardi musketeers. He was ably

helped by two of his Gardi commanders - Abu Aziz and Abu Shiekh. The constant

firing from the fort did its job. Close

to a hundred British soldiers died. Capt Abbington retreated his guns from Pir

Machi to the village of Taloja and also lowered the flag.

The Marathas also knew a couple of secret routes to the fort from the jungles to the east. As Abbington’s grip on the lower ranges of the fort weakened, Gangadhar Karlekar was able to send some much needed supplies and provisions to Ketkar. But the garrison left on Pir Machi stubbornly held out against efforts to dislodge it.

Nana Phadnavis, sensing that Gangadhar Karlekar was making little headway, now sent Balaji Phatak and Ragho Godbole to lift the siege. The two reached the village Shiravali in the first week of September and were joined by the others – i.e Karlekar, Dhulap and Kashipant . Turn by turn, the contingents of Anandrao Dhulap, Karlekar and Godbole attacked the British on Pir Machi, while Phatak supported them from their camp below and Pandurang Ketkar from the machi above. The Marathas managed to bring their cannon near Pir Machi and bombard the British positions. Considerable damage was caused to Abbington, but in the absence of a concentrated Maratha attack, they managed to hold fort. Finally, the 18th

of September was chosen as the day when a combined attack would be mounted on

the British. And in all probability, this would have meant the end of the

British siege, but nature had other plans in mind.

On the eighteenth

of September, it rained heavily at Malanggad, making any warfare impossible.

The entire region was shrouded in dense fog which made even the fort itself

appear just like a ghostly blur. The planned attack had to be put off for

obvious reasons.

British

counter attack

Abbington had not

been sitting idle on Malanggad. He sent messages to Major Westphal at Kalyan,

asking for help. Westphal responded by sending troops from Bhivandi, which cut

off the supply routes of the Marathas. Colonel Hartley started from Mumbai,

crossed the Thane creek at Belapur and taking the Belapur-Taloja route, reached

Shiravali, the Maratha camp. Here, a fight ensued between the Marathas and

Hartley and the former were driven back to the village of Vavanje.

Once again the

Marathas tried to storm Malanggad but this time had to face some fierce

resistance by Col Hartley and another officer named Jameson. The Marathas were

forced to retreat all the way to Barwai and further to Khopli. The British had

been weakened but not evicted. A Col Carpenter was now sent to aid the British

assault on Sone machi and the bale killa. A sincere effort to lift the siege

had thus failed.

Pandurang Ketkar was

once again left to fend off the British siege, as all attempts to lift it by

attacking from outside had failed. On his part, Col Carpenter had managed to

get his cannons into places where Capt Abbington had not. Two cannons were

hauled up to the base of Sone Machi. One was somehow fixed in the jungles to

the east. Finally, he positioned men in a natural cave below Sone Machi. And it

was now the month of October. The chance of rains was quite low.

Pandurang Ketkar, his two Gardi musketeers Aziz Khan Jamadar and Abu Sheikh Jamadar held off wave after wave of British attacks in the early days of October. Even concentrated attacks were repulsed with clever use of muskets and swords. Dozens of soldiers belonging to the East India Company were slain. The base of Sone Machi came to be strewn with the dead bodies of the enemy. Pandurang Ketkar had only a hundred or so troops, and they had valiantly held out for two whole months. Now, the British decided to evacuate the Pir Machi for a second time and established themselves in the village at the base of Malanggad. The next plan of action was to choke off supplies for Pandurang Ketkar. This was done by buying up the supplies all around the fort and also choking routes from the east. Very soon, only a fortnight’s supply was left.

The

siege lifts

Pandurang Ketkar fell ill in the month of November. But his repeated please to Pune finally had the desired results. Nana Phadnis realised that the contingents sent earlier were making little headway against Col Carpenter.

Nana Phadnis

decided to deploy ten thousand fresh troops. Along with Yashwantrao Panse,

Bhavani Shivram and Haripant Phadke he reached Khandala. Their plan was to take

the Rajmachi route and reach Kalyan. Bhavani Shivram and Panse were sent ahead

to Malanggad.

The East India

Company troops led by Col Hartley and Col Carpenter were hard pressed to find a

solution to this new threat. Plus the knowledge that after more than three

months of fighting on the fort, they had made little progress since the early

victory of capturing Pir Machi in August. They had lost hundreds in the

process. The British finally decided to lift the siege and take the risk of

heading towards Vasai.

Thus in November

1780, after a fierce fight of nearly four months the Marathas had managed to

beat back the EIC troops. It had largely been achieved through the personal

bravery of Pandurang Ketkar and his Gardi troops. He had held out till the

large reinforcement under Nana Phadnis materialised. Two sincere attacks on the

Sone Machi had been foiled by them and a mere hundred odd had managed to defend

the fort against all odds.

Aftermath

and lessons

The Maratha armies had been called upon to defend a hill fort perhaps for the first time since the Mughals had been defeated in the Sahyadris at the turn of the seventeenth century. A small garrison of just a hundred odd with depleting supplies had held out against hundreds of British troops and cannons booming all around them. The casualties inflicted were heavy, over two hundred of the Company’s soldiers died. In contrast, in 1818, many forts were taken with zero casualties on their side!

Although it ended

with the EIC threat staved off, there were quite a few things lacking on the

Maratha side. There was an intelligence failure in assessing that an operation

was planned for August. Warfare had improved in the hundred years since

Chhatrapati Shivaji had passed away. It was no longer impossible to begin

battles in monsoon. The Marathas kept to the old practices.

There was much

dilly dallying and indecision as regarded attacking Capt Abbington on Pir

Machi. The Marathas lacked an efficient chain of command. It was as late as mid-September

- nearly forty five days into the siege that a combined attack was planned.

Finally, it required Nana Phadnis to personally appear at the head of ten

thousand troops to force the issue.

The British troop

movements were better planned. Their August attack plan was well thought out.

What they lacked was the ability to effectively scale the hill fort. It also

made them realise that the hill forts, if equipped with a spirited garrison,

were very difficult to conquer. A point the Marathas missed in 1818.

All in all, it is a battle worth remembering for the stiff resistance put up by Pandurang Ketkar and his two Gardi commanders – Aziz Khan and Abu Shiekh which successfully defended the fort till its siege was lifted.

It forms a nice

story to go with a hill often sighted from Mumbai. The Ketkar family continues

to be the caretakers of the dargah on the hill.

References

1. The First Anglo Maratha War – M.R. Kantak.

2. Battles of Honourable East India Company – Naravane.

3. History of Marathas – Grant Duff.

4. Thane District

Gazetter - 1882.

Author

Aneesh Gokhale

has written three books, the latest one being 'Battles of the Maratha Empire'.

“Between the years 1659 and 1818, the Marathas fought hundreds of battles, not only in the Sahyadris, but across the country. Some of these were pivotal and game changing - such as the Pratapgad Campaign, Palkhed or Panipat. The course of Maratha and Indian history was altered by these battles. This book attempts to throw a light on a dozen of these significant battles and campaigns, focusing on the reasons, the chess - like moves and the effects of victories and defeats.” To buy book online and in kindle click Here