The

popular discourse in India has convinced the common man that our shastras are

unscientific and rigid. We have been brainwashed to believe that our shastras are conjectural and

hypothetical, with little or no relevance to modern life.

However,

anyone who has read the Natyashastra,

the

great Indian text on aesthetics and performing arts, would realize these are

conjectures of the

modern ignorant mind. Bharata Muni, the author of Natyashastra, has clearly stated that the theatrical experiments (prayoga)

and ideas of the time should be added to the shastra. It is thus an organic, living

classical text and not a fixed set of ideas and instructions.

Natyashastra is more for practitioners than academicians. The former practice

calls for constant experimenting that in turn forms the principles of

dramatics. Moreover the classical form of Koodiyattam, that is close to

the ancient Indian drama in many respects, is practiced even today. What more

evidence of a living text is required?

Like most playwright and theatre makers trained in Western

drama and aesthetics I believed plot and drama to be inseparable. At that point

Natyashastra, to me, seemed to be an outdated and complicated book used by our ancestors to construct plays. Its vocabulary was foreign and incomprehensible. While I was wrapping my brain around words like rasa and bhava my mentor and teacher, Dr

Bharat Gupt, suggested I attempt writing a Prahasana.

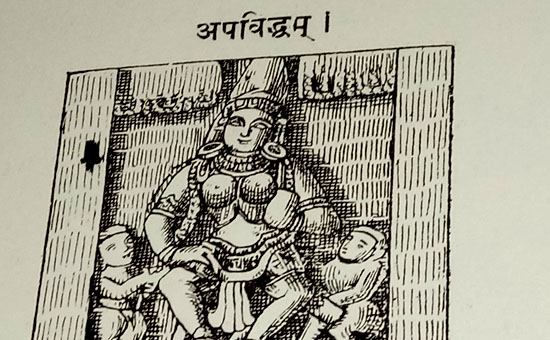

Sketch from Natyashastra

Sketch from Natyashastra

Now what is a Prahasana?

Prahasana is one of the ten genres/dasarupakas given in the Natyashastra.

Every rupaka has one dominant rasa. For instance hasya rasa

is the dominant rasa in a prahasana but there will be a dash of

other rasas as well. The prahasanas of ancient India were not

slapstick comedies. In fact some of them were sophisticated satires written by

prolific playwrights/poets of that time. The prahasana was a medium for poets to hit back at intellectuals, influential

and powerful people.

Also, the more I read the more I realized that the great

plays were not about a clever plot as much as they were about human condition,

world views, characters’ and their psyche – the intangible elements of drama. After

all great drama moves us profoundly - be it Arthur Miller, Mamet or Shakespeare.

‘Was it emotion or the plot that affected the spectator,’ is the question I asked myself? In its most elementary sense Rasa

is emotional arousal. To give an example, Tennesssee Williams is the master

of karuna rasa. You’ll cry buckets after watching ‘The Glass Menagerie’.

Nudged by my mentor and inspired by Indian thought I took up

the challenge to write a modern play using the rasa or Indian aesthetic

theory. My first experiment with Natyashastra, ‘Padma Shri Prahasana’,

started as a telephonic conversation with my mentor Prof Gupt.

Since the awardwapasi

group was making headlines in 2016 the play had to be a satire about those who

make newspaper headlines. The idea was not to recreate the old prahasanas or

copy the format completely.

So I retained the elements that would work with the modern

audience. For instance the tradition of juxtaposing opposite ideologies was

retained because therein lies the humour. In most ancient prahasanas the characters were somewhat caricatured to heighten

humour. I accentuated the flaws of the characters to achieve the same result.

What was different?

The tradition of reciting nandi and doing a prastavana

were not included. Ancient plays were much longer and played out slowly but

‘Padma Shri Prahasana’ had a tight and fast-moving script. The story and issues

were contemporary, actors quick on their feet and performance style modern.

Having said that, the format was at least 3,000 years old. To

continue the parampara I had a Sutradhar and the Vidushak open the play.

They joked and introduced the theme and characters – setting the mood and tone

of the play.

The format of a prahasana is relatively simple. For

instance most modern plays have nine plot points. But a prahasana has

just a couple incidents to move the plot. What matters is the theme. Prahasana

holds a mirror to society. So it is about finding the flaws and the flawed.

This genre gives you an opportunity to create interesting characters and their

worlds.

A play modelled on Aristotle’s Poetics has a strong

protagonist and an equally interesting antagonist. But typically there is no

antagonist in a prahasana. Most ancient prahasanas highlight the dissimilarities between various schools of thought for e.g. Buddhism and Saivism. Similarly ‘Padma Shri

Prahasana’ highlights the clash of tradition and Marxism and is something we

experience in our day to day lives. This format is unique to prahasana. What’s more every character and event should produce hasya rasa (laughter) in the spectator because hasya rasa is the dominant rasa in a prahasana. If the playwright and the team are not mindful of rasa siddhanta the audience will

disconnect. On the other hand when watching a well-crafted prahasana the audience forgets its worries and abandons itself to

the performance.

Padma Shri Prahasana performed at IGNCA, July 2018. By Akanksha Saha.

Padma Shri Prahasana performed at IGNCA, July 2018. By Akanksha Saha.

The first reading of ‘Padma Shri Prahasana’ was held at the

Habitat Center in December 2016. The Q & A session after the reading was

animated and thought provoking. For instance an audience member suggested we

change the location of the climax scene to India Gate. That small twist made

the scene more powerful and symbolic. An actor suggested I introduce a new

character who would be the epitome of an ideal musician. This new character

gave the audience a better understanding of the theme.

I rewrote the script, as per the audience and cast suggestions, before starting the rehearsals. The play was staged at IGNCA on 27th July, 2018. We had a full house and the audience laughed throughout.

‘Padma Shri Prahasana’ explores the theme of politics of awards and awardwapsi. The idea is to take a jibe at the award chase and the privileged class who wins awards and subsequently returns it to promote a certain political ideology.

Music is supposed to be sadhana and a path to

self-realization. But the musicians of the day are chasing awards and concerts.

Awards lead to concerts, concerts bring visibility which brings networks and

networks bring awards. The nexus between artists, intelligentsia, politicians,

and bureaucrats is exposed and ridiculed in this play. To a lesser extent, the

theme of class clash in Indian society was explored.

The ending of the play neatly sums up the theme, “Music is

sublime. Why limit your consciousness to awards? Let’s lose ourselves in music

and seek the limitless peace of notes.”

The contrast between the Indian philosophy of music and the

commercialization of arts has been juxtaposed. I borrowed from Late Kishori Amonkar’s interviews to create a character that epitomizes the philosophy of Indian classical music. Next a middle-class Sanskrit professor and an Anglophonic political science professor are brought face to face to dramatize the clash of tradition and Marxism. The Sanskrit professor represented the common man while the political science one represented the elite influential class.

The debate between the professors was the most entertaining

part of the play. In a modern play the characters do not stand on stage and

debate since it is believed that modern audiences do not appreciate that.

Instead the thrust of the modern play is ‘to show rather than tell’.

Conversely, the format of prahasana

allows these debates to be slipped into the fabric of the story without seeming contrived. The debate may seem to stall the action of the story but it does not bore the audience. So the Western dramaturgy experts may have got it wrong all along when they

insisted that conflicts should not be spoken out on stage. It would not be out

of place to mention that Indian philosophy allows for discussions of

differences and debate, may the best win. Remember the classic debate between Adi

Shankara and Mandana Misra.

By the looks of it, the first attempt at prahasana was

a success. To my mind, the success is not in just using the format for

constructing a play but also in following the conventions of ancient times.

Dr Bharat Gupt advised us to shun European realism and

experiment with non-naturalistic style. Non-naturalistic style meant doing away

with the real furniture and property. Not only did this style bring down

production cost, it also gave the actors a chance to explore ‘angik

abhinaya’ (body and gestures). Actors mimed actions like drinking tea,

paying money and the property was created in the minds of the audience with

acting and dialogue. This style made the acting more humorous. The play

revolves around the lost Padma Shri certificate, a certificate that was

never brought on stage – it remained an abstract idea of success. The frame for

the Padma Shri became a metaphor for ego. Hence, non-naturalistic style

added layers to the play and made it even funnier.

I

would encourage playwrights to explore the other rupakas/genres. We must

continue to experiment to not only create new works but also to challenge the

Western dominance of performing arts.

About Author: Rashma N. Kalsie’s plays have been performed around Australia and India. Rashma’s writing credit for the theatre include award winning Melbourne Talam, Padma Shri Prahasana, The

Lost Dog, and The Rejected Girl. TV credits include scripts for

close to 100 episodes of Indian TV shows/docudrama. Book Credits: Ohh! Gods Are Online (Srishti

Publishers, India) co-authored with a British writer. The Buddha & the

Bitch (Hay House, India) co-authored with an American poet. Rashma has published articles and short fiction in print and online magazines. She is also a research associate with Vision India Foundation.

To buy her books

online

Also read

1 Natya Sastra Translation by Babulal Shukl Shastri

2 Dramatic Concepts, Greek and Indian: A Study of the Poetics and Natyasastra by Dr Bharat Gupt

3 Manmohan Ghosh's English translation of Natya Shastra

4 Classic Debate between Sankara and Mandana Misra