-

Article tells about origins of snake worship esp. in India, its practice in North, East and South

India.

The Naga worship or Serpent worship (also

known as Ophiolatry) is among the oldest and most widespread forms of religious

practices in that the world.

In the minds of the early men there

were a fear of the nature and powerful animals, with a feeling that they were

stronger and wiser than him, or in short: uncanny. This was esp. true of the

snake or serpent because of its swift, mysterious, yet graceful gliding

movements without possessing any feet or wings, it’s fascinating eyes, the

power to disappear swiftly, shedding of its skin which gave a sign of

immortality, and the deadly consequences of its bite.

All these characteristics produced

mixed feelings of fascination, fear and respect, which led to the start of

serpent worship, and a subject of many myths and folktales. In the cults that

worship animals, such as the Naga cult worshipping serpents, there is generally

found among its followers a strong belief in the animal’s magical powers,

beneficence, healing powers, wisdom, and the possession of secret higher

knowledge.

In the ancient world serpent worship

was popular and universally practiced in Arabia, Persia, Asia Minor, Syria,

Egypt, Italy, Greece, in many parts of northern and Western Europe, the current

Latin American nations, China, Sri Lanka, and Japan.

However, the Naga cult assumed

special importance in India, and unlike the other nations it took a more

developed form with many interesting variations, and was also more widely

distributed. India is also a country which always had a wide distribution of a

variety of snakes, and the large number of deaths that took place from their

venomous bites explain why the serpents or Nagas were feared, respected, and

worshipped from prehistoric era.

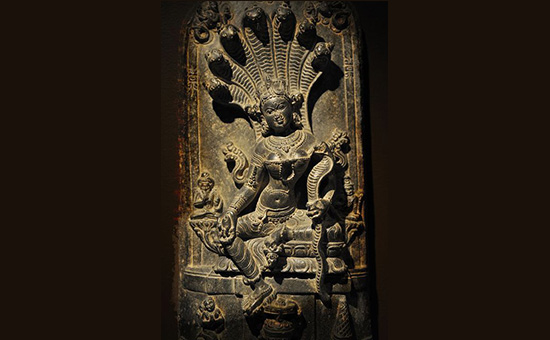

Manasa devi, the Goddess of Serpents.

Manasa devi, the Goddess of Serpents.

She is popularly worshipped still today in the states of West Bengal and

Odisha.

Textual References to NagasThere are innumerable references to the Naga

worship cult in the ancient Indian scriptures, such as the Vedas, Epics, Sutras

and in many other literature.

While the worship of the Naga was in its initial

stages in the Rig-Veda, it became a regular

object of worship in the Yajurveda, with offerings of

various sacrificial items. The Rigvedic term Ahi budhyna, meaning

the “serpent of the Deep” could be a representation of an atmospheric deity,

with a figurative form of a serpent. Atharvaveda gives

more details of the Naga worship and is filled with many charms and incantations

against snakes, and also describes a rite for gaining the favour of the Naga

devta on the full moon day in the month of Agrahāyaṇa/Mārgaśīra. Atharvaveda

also mentions names of many snake gods (such as Asita, Rabhru, Kairata,

Prsna, Apodaka, Taimata, etc) in different contexts, and sometimes

associates them with the gandharvas, yaksas (punyajanas), apsaras:

Gandhravapsarasah

sarpandevanpunyajananpitrrn |

Five such snake gods Tirasciraji, Prdaku,

Svajo, Kalmasagrivo, and Svitro are believed to be the

protectors of the southern, western, northern, eastern, and upper quarters. In

Atharvaveda there is the first mention of the famous Taksaka described

as the descendant of Visala (Taksako Vaisaleyo).

The Epics (Mahabharata and Ramayana) are also full of references to the Nagas in various

ways. Dhrtarastra, the son of Iravant, is said to be the person who milked

poison, (the subsistence of the nagas) from Viraj (Universe),

and is mentioned as the best of the Nagas in Mahabharata. Mahabharata also

mentions another Naga by the name Manimat, alluding to the belief

that snakes bear jewels on their hoods. This belief is an ancient one, and as

Varahamihira says “the snakes of the lineage of Taksaka and Vasuki and the

snakes roaming at will (kamagah) have bright blue tinged pearls in their hoods”

(Brhatsamhita, LXXXXI, 25).

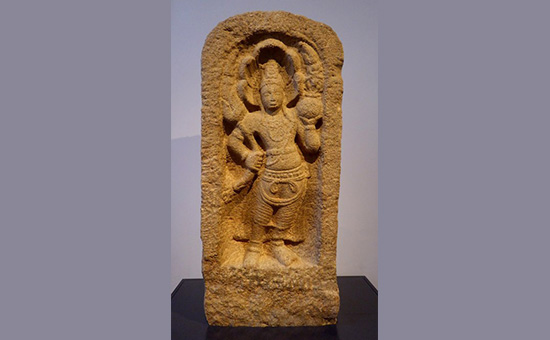

Naga devi, Rajarani temple, Bhubaneswar.

Naga devi, Rajarani temple, Bhubaneswar.

The

Nagas found a place of great importance among the Vedic and post Vedic deities,

and the Gryhya Sutras include a ritual known as Sarpabal, which was an annual rite that took place

for four months during the rainy seasons, and was held specifically for two

fold reasons: honouring the nagas and also warding off all evil from them.

The

tradition of worshipping the Ashtanagas (Taksaka, Vasuki, Ananata/ Sesha, Karkotaka, Shankhapala, Gulika,

Padma and Mahapadma), and Manasa (the goddess of snakes,

very popular in West Bengal and Odisha even today) during the monsoons, and

on Nag Panchami day (in the month of Shravan) are a modern day

continuation of the Sarpabali ritual.

Manasa Devi, Pala

era 12th c. CE, Bengal, Rubin Museum of Art, New York.

Manasa Devi, Pala

era 12th c. CE, Bengal, Rubin Museum of Art, New York.

Besides

Hinduism, Nagas have also found a place of significance in Buddhism, Jainism,

Sikhism, and in other local and regional cults, as clearly evident from their

religious monuments, sculptures, paintings, literature, tradition, and folk

tales.

The

Buddhist text Cullavagga (v.

6) names four tribes of snake kings that are: Virupakkha, Erapatha

(Elapatra), Chabyaputta, and Kanhagotamaka, of which the first two are

well known in many Buddhist texts. The Buddhist texts also refer to the Naga

chiefs Mucalinda, Apalala, Kaliya, etc. who all pay respects to Buddha in

various contexts.

Similarly

Krishna’s victory over the Naga Kaliya in Mathura, speaks of the domination of

the Krishna sect (Vaishnvism) over the more primitive Naga cult.

Interestingly the census report of 1891 prepared by the British government in India contains a detailed account of the distribution and number of snake worshippers in different parts of the country. At that time “there were 35,356 worshippers of Naga and 12,2991 worshippers of Snake hero Guga pir with other groups in the United provinces of Agra and Oudh, In Punjab 35,344 worshipped Guga,”(Census Reports of

India, 1891.)

James Fergusson in his book “Tree and Serpent worship” has written about the worship of live snakes in Manipur and Sambalpur (Orissa). A snake temple at Calicut kept many live Cobras that were taken care of by the priests and worshippers. The snakes were carefully protected and allowed themselves to be handled and made into necklaces by those who fed them. They were worshipped as representing the spirits of ancestors.

(M.A.Handley,

Roughing it in South India, London, 1911, pg 70.)

Iconographic Development Apart from ancient Vedic and other

literature to the medieval era texts that give innumerable descriptions of Naga

worship, there are also epigraphic records that show the Nagas in primarily

three different iconographic forms:

In the first form the serpent is many headed.

In the second type,

it is shown in a human form with a polycephalous serpent hood.

The third type

combines the two, where the upper part is that of a human body while the the

lower half is that of a coiled snake.

The second type: a human form with a polycephalous serpent hood.

A

granite Nagaraja from Sri Lanka, (800 to 900 CE). Now on display at

the Victoria and Albert Museum in West London. (Photo from

Wikipedia.)

Third type. Nag Kanyas, Megheshwar Temple, Bhubaneswar.

Third type. Nag Kanyas, Megheshwar Temple, Bhubaneswar.

The Nagas appear early in

the Indic religious scenario as evident from the excavation finds from the

Harappan culture. Among them, there are two seals from Mohenjo daro that depict

a seated deity in yoga posture, with two kneeling figures one on either side,

and behind each figure is seen a snake head raised with expanded hood. Besides

these, snakes have been found painted on Harappan potteries, and a clay amulet

has been found where a snake figure is seen in front of a low stool on which

there seems to be some kind of an offering.

The iconographic traits of the Nagas as found defined

in the Mayasamgraha says that

Nagas have two tongues and hands, 7 hoods with jewels on them, in one hand they

carry aksmala or jaomala, and have curling tails as their lower body part. The

Naga women and children have one or three hoods. I

In Vishnudharmottara,

Ananata Naga is depicted as four armed, having many hoods with bhu-devi

standing on the central hood. In his two right hands should be placed a lotus

and a pestle, while his left hands should carry a plough and a sankha. There

are further mentions of ‘sea of liquor’, ‘palm tree,’ and various other things

that show a definite connection with Samkarsana/ Balarama.

The text Silparatna (compiled

in 17th century) say that Nagas are humans from naval upwards, and their lower

parts are serpentine. There are hoods encircling their heads and their numbers

vary from 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9. They should have two tongues, and in their two

hands should be shown a sword and a shield.

Some of the earliest representations of Nagas in the historic

period are of Elapatra and Chakravaka on Bharhut railings (2nd c. BCE). Both

are full humans with five hooded snake heads on top and in namaskara mudra

showing respect to Buddha.

It is the Naga images

found from Mathura area dating back to the Kushana period that depict them as

strong cult objects enshrined by their devotees.

A Naga image found in

Chargaon near Mathura is a typical cult object with 7 hoods and serpent coils

visible both in front. Here the dual nature of the Naga devta is shown by sculpting

a human being standing in front of the polycephalous snake. This form is very

similar to what we see in Balarama. In fact such Naga murtis often still

receive worship in the villages, but under different names where they are

referred to as Dauji (elder brother) or Baldeo ( Balarama).

With the decline of

Kushana Empire the Naga worship cult spread in and around North and Central

India where they found other royal patronages. This is corroborated

by the fact that innumerable epigraphic, numismatic, and literary evidences

have been found at Taxila, Padmavati, Vidisa, Mathura, Kantipura, and Ayodhya

that talk of Naga worship.

From the few available

coins of a ruler named Virasena (his capital was at Mathura) are seen the

images of a serpent rising over the throne on which a female figure is seated

(could be devi Ganga) holding a kalasha in her raised right hand. The coins of

three kings Kumudasena, Dhanadeva, and Visakhadeva (likely kings of Ayodhya

between 150 BCE and 100 CE) depict snakes as one of the symbols on them.

The Naga family of

Mayurbhanja (Odisha) known as the Virata Bhujanga /Vairata / Virata, had Naga

deva as their kul devta. The Patamundi hill near Puradaharis was once a seat of

a Naga devi, which bore a testimony with the carved image of Kinchaka Naga.

Another example of the Naga cult was seen at the excavation site of Maniyar

matha in Rajgir, which held a temple built in the Gupta period dedicated to the

Nagas, and was known as Naga-Ghara.

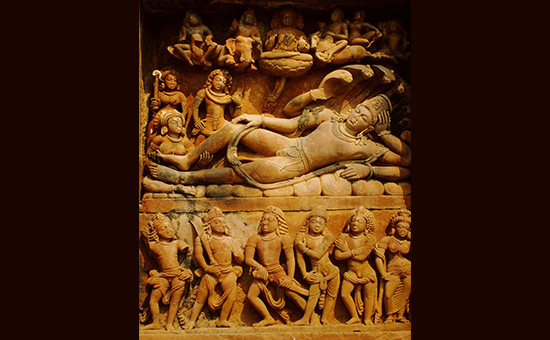

This strong Naga cult

however lost its importance in the northern part of India from the time of the

Gupta period, as is evident from the fact that they turned into accessories of

the higher gods, especially Vishnu. While their hybrid iconographic form was

continued, but when shown as Sesha or Ananta Naga with Vishnu sitting or lying

down on it, they were depicted as huge polycepahlous snakes.

Vishnu on Sesha Naga, Dasavatara temple, Deogarh. Gupta period. Pic from

Wikipedia.

Vishnu on Sesha Naga, Dasavatara temple, Deogarh. Gupta period. Pic from

Wikipedia.

In

South India the Naga worship has a stronger

presence even today, and it is common to find Kavu or snake groves (resembling

the Nagavana of North India) usually known as Vishattam kavu or poison shrine

or Nagakotta.

That

Naga worship was prevalent in Southern India from ancient times is known from

an inscription at Banavasi written in Kannara, which records the erection of a

snake stone in the middle of the 1st c. CE.

Snake

stones are still common in almost all villages in south India, and they are

also frequently seen under vata or asthwa trees within temple complexes, or in

separate shrines inside large temple complexes.

References

1.

J. Fergusson, Tree and Serpent Worship. London,1873.

2.

J.P. Vogel, Indian Serpent Lore, London, 1926.

3.

A. Cunningham, The Stupa of Bharhut, London, 1879.

4.

V.A.Smith, Catalogue of the coins of the Indian Museum, Calcutta, 1907,

pp.148-50.

5.

N.N.Vasu, Archeological Survey of Mayurbhanja, Vol.I, Calcutta, 1912

6.

V.S.Agrawala, Ancient Indian Folk Cults, New Delhi, 1970.

7.

TAG Rao, Hindu temple iconography, 1914.

To read all

articles by author

Author studies life sciences, geography, art and international relationships. She loves exploring and documenting Indic Heritage. Being a student of history she likes to study the iconography behind various temple sculptures. She is a well-known columnist - history and travel writer. Or read here All pictures by author barring one of Raja Rani Temple and Nag devi which are by Sanjeev Nayyar.

Article

was first published on author’s blog and here Article and

pictures are courtesy and copyright author.