- Article explains the meaning and significance of Kirtikukha in Indian temples. They are found in Hindu and Jain temples, in Bodh Gaya Temple too.

One of the most intriguing and a common feature among the

Hindu temple adornments is the Face of Glory or Kirtimukha. The half human -

half animal face, swollen with the intake of breath, is most prominently seen

on the sukhanasa, in the centre of the arches of littles niches or shrines, the

apex of windows, in front of the threshold of the garbhagriha on either side of

the lotus stalk in the centre, on cornices, pillars, and also walls. Kirtimukha

is also frequently seen in a row on the temple bases or socle, and is termed as

Grasa-pattika (Gujarat) and Rahurmukhamala

(eastern India). In south Indian temples it is seen on two sides of the steps

at the base of the temple.

Thus, this face of glory with its dark grin is seen looking

out from both the apex and base points of temples.

Kirtimukha. Warangal fort ruins of Sri Swambhu temple.

Kirtimukha. Warangal fort ruins of Sri Swambhu temple.

Full caption 2 - Kirtimukha.

Warangal fort ruins of Sri Swambhu temple from the Kakatiya era. The kirtimukha

seen here would have once been a part of the temple ceiling embellishments.

Kirtimukha has its equivalents in the Chinese T’ao T’ieh known from around 1st

millennium BCE; and in the medieval European architecture where it is seen

in the Notre Dame, and in English churches where it is often known as the Green

Man.

What is kirtimukha and what does it look like

The kirtimukha most often has the face of a lion

and is also known as simha mukha or the lion faced. It has two horns, with a

third or middle horn in the forehead centre, just above the two bulging eye globes

that protrude out of their deep sockets. The entire face with its carvings

gives the impression of deep inspiration through the nostrils, and the breath

restrained between inspiration and expiration across the bridge below the eyes

and over nose.

Rahu’s head or kirtimukha. Brihadeswara Mandir, Tanjore.

Rahu’s head or kirtimukha. Brihadeswara Mandir, Tanjore.

Rahu’s head or kirtimukha is seen in the apexes of

the tall gopurams, and repeated on gavaksha emblems throughout the temple

superstructure, on the bhumis, and cornices of south Indian temples where it is

depicted in its full meaning, as the Head, and Prakriti in the arch below it.

Seen here are many kirtimukhas in the apexes of the gavakshas on a Gopuram of

the Brihadeswara Peruvudaiyer temple in Tanjore.

Kirtimukas in bands known as Grasapatti or Rahurmukhamala as moulding embellishments.

Kirtimukas in bands known as Grasapatti or Rahurmukhamala as moulding embellishments.

While kirtimukhas were present in Indian art and iconography

from the times of classical antiquity (beginning of Common Era or perhaps even

before that, as for example horned kirtimukhas from Sirkap in Taxila), its most

developed form is seen from 10th century onwards when it became a fixture on

the sukhanasa gavaksa.

If observed closely it will be seen that the kirtimukha is an

incomplete face with no lower jaw, and from below its protruding teeth emerge

the arch of the gavaksha and the other forms seen around it. The entire arch

formed around or below the kirtimukha is often filled with ganas and other airy

forms seen flying towards the centre of the archivolt, where in Odisha temples

we find a bell hanging.

Kirtumukha on the sukhanasa gavaksa, where a

bell hangs from the centre of the archivolt. Mukteswar temple, Bhubaneshwar.

Kirtumukha on the sukhanasa gavaksa, where a

bell hangs from the centre of the archivolt. Mukteswar temple, Bhubaneshwar.

The outside edge of the gavaksha arch is filled with curvy

carvings denoting foams, waves, and wings. All these are an extension of the

makaras that lie at the arch base forming the two ends; and often these makaras

are seen protruding from beneath the puffed up cheeks of the kirtimukha. When

makaras form the base ends, the kirtmukha is known as Kala-makara.

The inner circle of the gavaksha is open and in the lower

part is generally is seen an aspect of the main deity of the temple, or it has

a lotus in it, and this lotus corresponds to the lotus at the apex of a prabhatorana (seen in many murtis from

eastern India) giving it the same meaning as a kirtimukha, where both symbolise

the threshold.

Kirtimukha at the premier position in the

famous Gupta temple, Nachna Kuthar, Panna.

Kirtimukha at the premier position in the

famous Gupta temple, Nachna Kuthar, Panna.

Kirtimukha on top panel of a temple wall niche, Baseswara temple, Bajoura, Kullu district.

Kirtimukha on top panel of a temple wall niche, Baseswara temple, Bajoura, Kullu district.

Kirtimukha is also known as Grasamukha (western India) or

Rahurmukha (eastern India). It also represents time or Kala. The word Grasa, which means to devour, can be seen at parity

with Rahu who devoured the sun and moon, symbolising the Solar and Lunar eclipses.

Kala is also a devourer, the greatest one, which devours everything at the end.

Thus, the three names frequently associated with the face of

the Kirtimukha are synonymous. The kirtimukha or the Face of Glory as we see

depicted on temples contains in it three parts: a Lion’s face, the head of Rahu

(also loosely referred to as dragon’s head, as some believe Rahu has the shape

of a serpent), and the head of Death (Kala). The Lion, which is the solar

animal, symbolises Yasas- tejas (Splendour) and the Destroyer of all evil.

As per the Upanishads/Vedanta, Paramveswara or the Supreme God is represented by the Lion; and we

see this in the Narasimha avtar, where the Lion is Vishnu - Narayana and Nara

is the body or jiva (the creature). It is also Vishnu Narayana who cuts off

Rahu’s head, and with this death gesture restores life to the Eternal, the

immortal Head, now released from the ties of the worldly body of strife and

deceit.

In the mask of the Kirtimukha, the breath that gives power

and splendor belongs to the simha mukha with its blazing eyes. Behind this

visible face is the sun or the Eye of the All (as per Rig Veda), where “behind

the Death’s head, the mask is inflated with breath, the outbreathing of the

Supreme which is and makes the world.” The triple horns, which are rays,

denote the three aspects of the Lion, Rahu, and Kal; and also represent the

three aspects of time - Past, Present and Future (Shiva’s trident).

Daulatabd fort, kirtimukhas from one of the

destroyed temples of the Yadavas. Stalked lotus in the middle. This would have

been the threshold at the entrance of the temple sanctum.

Daulatabd fort, kirtimukhas from one of the

destroyed temples of the Yadavas. Stalked lotus in the middle. This would have

been the threshold at the entrance of the temple sanctum.

Kirtimukha, Warangal Fort.

Kirtimukha, Warangal Fort.

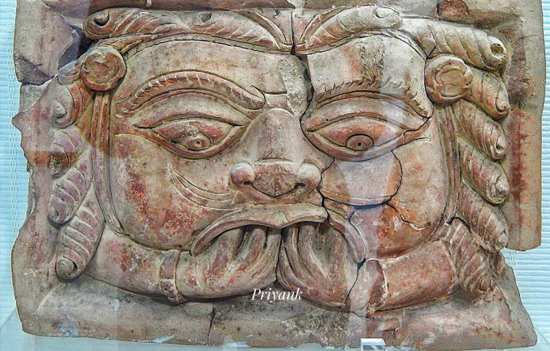

Terracotta plaque showing Kirtimukha, Nalanda.

Terracotta plaque showing Kirtimukha, Nalanda.

The three aspects of the Kirtimukha are –

1. It is the Death head of Kala or Time, the Devourer

or Grasa of Rahu;2. The Death’s head has in it the essence of Ahi Vrtra

(the Purusha) who himself holds splendor, all wealth, knowledge, and gods; who

has no hand or foot, is the source of solar power, and the creature that

envelopes the Universe and also emits it; and3. From the Lion’s open mouthed out-breathing Supreme

Brahman is emitted and sent out, thus giving life to the world.

Mahabharata (XXX.47.17) says that the 3 bodies of the Kirtimukha are also

that of the Shiva’s: Kala, Purusha, and Brahman.

The Kirtimukhas reveal that the world is a

result of the outbreathing of the Supreme Brahman, and this is shown as the

waves and curls that emerge out of the mouth. It moves along the curve and arch

of the gavaksha (which is an imagery depiction of the Sun and manifestation).

The breath moves around and often takes multiple shapes, such as foam of the

celestial waters, feathers of the sunbirds, flames (Agni was the first to

emerge from the Breath of heaven – RV. V. 45. I) and makara bodies.

Thus, the rhythmic pattern of the creepers

depict the movement of the breath, and is the symbol of Nature or Prakriti that

manifests itself as the curve of the gavaksha in which the rays of splendor

have their circumference. All the carvings and depictions seen along with Kirtimukha are imagery depiction or bringing forth to life the lines from Taittriya Aranyaka: “O waters whose steeds are the winds, whose lords are the rays of the sun, whose body is formed of shining rays… May the heavenly waters and herbs be auspicious to us and may they bring happiness…”

Kirtimukha above the gavaksha of the central niche, Jain Temple Osian.

Kirtimukha above the gavaksha of the central niche, Jain Temple Osian.

The various Puranic stories and other legends associated with kirtimukha

As per Skandapurana and Padmapurana,

just when Shiva was about to marry Parvati, Rahu as the messenger of Jalandhara

came asking for Parvati. Shiva in his anger produced a monstrous being from his

third eye that had the face of a lion with lolling tongue, standing hair, and

with eyes like lightning (looking like Narasimha), which rushed to kill Rahu;

however Shiva stopped it and instead ordered it to devour itself. This it did

as an act of self-sacrifice, leaving only the head, which is the Kirtimukha.

Thus, kirtimukha is a part of Shiva’s

Consciousness, where we find Shiva in his terrific aspect of Mahakaal sharing

the features of Kirtimukha as Kaal. Kirtimukha is also similar to the head of

Vishnu avtar of Narasimha.

The two Puranas (Skandapurana and Padmapurana)

further add that kirtimukhas must be seen at the entrance of temples dedicated

to Shiva, and they must be worshipped first before the devotee enters the

sanctum. That is why it is found on front of the threshold of the shrine, where

devotees sprinkle water on it and take care not to step on it.

Kirtimukha or Simha mukha on front of the threshold of the Shiva shrine,

Someswara temple, Bhangarh fort.

Kirtimukha or Simha mukha on front of the threshold of the Shiva shrine,

Someswara temple, Bhangarh fort.

A Lingayat legend tells us that after killing Hiranyakasipu

(Simhika’s brother; hence Rahu’s uncle) Narsimha had turned arrogant. To stop

him for causing further destruction, Shiva killed Narasimha, and out of the

severed head of Narasimha, Shiva made the kirtimukha.

Kirtimukha above Narasimha showing similar

features. Kalikapurana tells us that Narayana is the

simha part in the Narasimha avtar.

Kirtimukha above Narasimha showing similar

features. Kalikapurana tells us that Narayana is the

simha part in the Narasimha avtar.

Reference

1. Stella Kramrisch, The Hindu temple.

To read all

articles by author

Author

studies life sciences, geography, art and international relationships. She

loves exploring and documenting Indic Heritage. Being a student of history she

likes to study the iconography behind various temple sculptures. She is a

well-known columnist - history and travel writer. Or read here

Article

was first published on author’s blog and here

Article and pictures are courtesy and copyright author.