- This photo essay, with pictures, covers the Architectural

significance of temples, the development of and regional variation of temples.

1. Introduction

The temple is considered a zenith of Indian architecture and is identified as the soul of Indian culture worldwide. In Indian culture the temple structure, that we see today worldwide, is an architectural expression of India’s intangible culture.

The paper focuses on the architectural development of

the temples which could be traced based on the archaeological remains to date.

From whatever remains of the structures, one can see a very systematic

development of the temples. This development can be traced back to Saraswati

civilization till late in various parts of the world, from a very small place

in a household to large temple complexes.

Also, many cities have grown around temples and many

are temple towns. India has many living temple towns like Srirangam, Ujjain,

and Madurai as well as cities which are cities of temples, like Kashi.

2. Temple - A Concept

The word ‘temple’ is derived from the Latin word “templum” means a “sacred precinct” which is reserved for religious or spiritual activities, such as prayer and sacrifice, or analogous rites (Fletcher -1961).

Traditionally, the temple is a sacred structure and also indicative of the abode of god or gods. However, in the Indian context, ‘temple’ not only is the abode of God and a place of worship, but they are also the cradle of knowledge, art, architecture and culture. Amongst other architectural geniuses in India, temples are one of the oldest forms of architectural manifestation of Indian culture. The temples that we see today have gone through an elaborate process of evolution over centuries.

Ganga Arti at Kashi.

Ganga Arti at Kashi.

The temple is essentially a vehicle of religion, built for the fulfilment

of the spiritual desires of the people. Although primarily the temple was a centre

of worship, it also had wider socio-cultural dimensions in India (Dayalan

1992). Religion, in ancient India, as in other ancient and some modern

civilizations, was all pervasive and there was hardly any aspect of life which

remained unaffected by it. The temple, being a visible embodiment of the

religious aspirations of a vast majority of people, played an equally vital

role in all fields of human activity (Shastri 1980).

The temple was a nucleus around which revolved

the entire life of the society.

Indian temple is a total

of architectural rites performed based on its traditional practices. The

principles are given in the sacred books and structural rules in the treaties

on architecture. The structure of the temple is rooted in Vedic tradition, and primaeval

modes of the building have contributed to its shape (Kramrisch 2015).

As mentioned by Author and Indic Scholar Subhash Kak, temples are mentioned in Panini’s grammar (500 BCE). Also, scholars have worked on also how "the prototype of the temple goes back to the Agnicayana rite of the Yajurveda. The sacred ground for Vedic ritual is the precursor to the temple.” It is a structure designed to bring human beings and gods together, using

symbolism to express the ideas and beliefs of Hinduism (Michell 1977).

Vimana, the name of the main temple building, is synonymous with Prasada. These

two are the most significant words for the temple. This is in complete

conformity with the meaning of the temple and the bricks on which it is built.

They are instilled with the presence of Siva and all the principles of

existence (The Agni Purana, 41.11).

Other words for the temple are:

1. Devagrham, Devagara (manusmṛti, ix. 280), houses of god;

2. Devayatanam, Devalaya, Devakulam, meaning seat or residence of God;

3. Mandiram, Bhavanam, Sthanam, Vesman, meaning waiting or abiding place,

4. Dwelling, Abode, Station, entrance or dwelling, respectively Alayam, Kirtanam, Harmyam a Palatial building and Vihara.

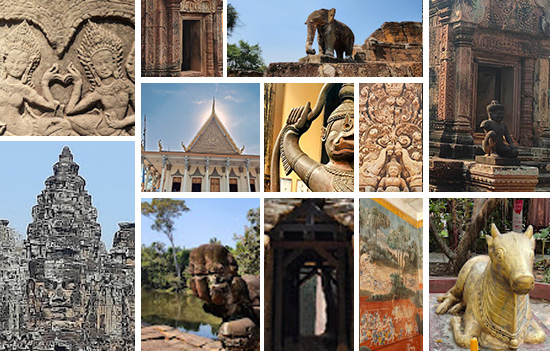

South-East Asia has always been a topic of discussion for its cultural roots embedded in India which is significantly visible. Even in other parts of the world, the traces of the temples can be seen in different forms. Southeast Asia still has larger remains of temples, for e.g. Ayutthaya in Thailand, the Sanctuary of My Son in Vietnam, the temple of Borobudur in Indonesia, and the temple of Angkor Wat in Cambodia, which show very strong similarities to Indian architecture. At a glance, it always gives a sense of ‘Indianness’ to this region.

Summary of Indic Heritage in Cambodia. Pic by Divyaroop Bhatnagar.

Summary of Indic Heritage in Cambodia. Pic by Divyaroop Bhatnagar.

When the Indian poet Rabindranath Tagore paid a visit to today’s Indonesia, then Dutch East India (NederlandschOost-Indië) at the beginning of the 20th century, he is reported to have announced the words given

the independent internalization of the Indian culture, “Everywhere I Can See India And I Do Not Recognize It Again!”(Lukas, 2001).

Albums Hindu Symbols in Thailand + Ayutthaya + Prambanan Temple Java

Culturally speaking, this larger region, is characterized by the deep

traces of the Indian Sanskriti that occurred long ago. The importance of

Sanskrit in the vocabulary of the languages spoken there, the Indian origin of

the alphabets with which those languages are still written, the influence of

Indian law and administrative organization, the persistence of certain Indic

traditions in the countries, which in architecture and sculpture, are

associated with the arts of India and bear inscriptions in Sanskrit. (Codes

1975)

Read Samkriti,

Sanskrit and Indonesia by Guru Anand Krishna ji

Prof. George Coedes defines this region of “Farther India” as ‘Indianization’ which is ‘the expansion of an organized culture’ that was formed upon Indian conceptions of Royalty, Hinduism, Buddhism and the Sanskrit language’.

Angkor Wat temple, Siem Reap province, Cambodia.

Angkor Wat temple, Siem Reap province, Cambodia.

3. Temple development in India- at a glance

The concept of god goes back to times immortal, however the architectural form can hardly be seen through archaeological remains. The smaller form of the abode of god starts appearing in the Saraswati civilization, though the function of these spaces is not yet confirmed as a “temple”. As per Dr. Kak, the sacred ground for Vedic ritual is the precursor to the temple.

The prominent presence of temples can be observed after the period of 3rd

BC with findings of murty, images of gods on coins etc. After the reign of

Ashoka and the collapse of two powerful dynasties, the Kushanas (236 AD) in the

north, and the Andhras (225 AD) in the south, Buddhism suffered from a lack of

political patronage leading to its slow decline. The age that followed had a

large part of the country coming under the political control of the Gupta

dynasty, which reached its zenith around 400 AD.

Read About the Gupta Empire and Kings

Architecturally speaking, this period starts with imitating architectural

elements from wooden architecture with a new sensitivity in the handling and

use of stone. This was the first time that the use of dressed stone masonry was made,

a major step in the evolution of building construction. With this, a radically

different type of architecture began to evolve.

Hereafter Indian temple architecture passed through the age of

experimentation, corresponding to the need. In the Gupta period, a garbha-griha in stone evolved. The form

of the temple is small and simple e.g. this modest structure at Sanchi complex.

Gupta period temple, at Sanchi Stupa complex.

Gupta period temple, at Sanchi Stupa complex.

This has all the main characteristics of early Hindu temples - an inner

garba-griha with an outer veranda/ portico with columns in the front, and a

flat roof of stone above. Though it is a basic structure when compared with the

later elaborate large temples, its details are worth noting. It seems to be a

well-thought-out structure with optimum important space for deity and worship. One

can notice the water spouts for rainwater drainage in the top part of the structure

along the stone edge, which can be seen in the above picture!

A similar form of a structure can be seen at Udaigiri in Madhya Pradesh

where in the garbhagriha is rock-hawn and the small mandapa is a structure

constructed out of stone. The early Gupta period

reached its zenith with the construction of a little Vishnu Temple at Deogarh,

in Jhansi district which is remarkable for several reasons. An effort is seen

to enhance the grandeur of the temple by raising the temple Garbha griha on a

platform, having a pyramidal roof over it, and discarding the till-used flat

roof. The whole structure is placed on a pedestal, thus adding to the height of

the temple. This would be a panchayatan

temple once, which now has only traces of plinths or the profile of the platforms.

From the recent excavations, the ruins of plinths of the other temples are also

found in the geometrical alignment of the main Vishnu temple in the same

complex.

Devgarh temple in Jhansi district, Uttar Pradesh.

Devgarh temple in Jhansi district, Uttar Pradesh.

Gajendra-moksha story carved on Devgarh temple, Jhansi, India.

Gajendra-moksha story carved on Devgarh temple, Jhansi, India.

Almost simultaneously, a similar movement was taking place in the south

under the direction of the Chalukyas (AD 450 to 650). The main effort of this

dynasty was at Aihole where one finds almost 70 shrines and temples, all in

stone. Aihole is considered as the cradle of Indian Temple architecture.

Similar to the Gupta examples, the temples at Aihole for the most part

are flat-roofed, though a few temples have pillared hall or mandapa in front of

the temple e.g. The Ladhkhan temple. To see album of Temple Pics 30 and 36 and Durg Temple Aihole. This is also the best example to see the imitation of wooden structures

in stone. The elements required structurally in wooden structure are copied in

stone as is, though not a structural requirement, when the structure is

constructed out of stone.

Ladkhan temple, Aihole, Karnataka.

Ladkhan temple, Aihole, Karnataka.

Sri Vishnu at Ladkhan Temple, Aihole, Karnataka.

Sri Vishnu at Ladkhan Temple, Aihole, Karnataka.

Durg temple, popularly known as Durga temple at Aihole. This is an

example of the form of a Buddhist Chaitya hall, adapted to suit the Hindu

ritual. The apsidal hall has a small tower over its end to give the appearance

of height. The chaitya shaped is used for the Parikrama path (circumambulation)

around the garbhagriha, Antarala and mandapa. A kakshasana (mandapa with seating created in stone) is a common

feature in these temples at Aihole, which seems to have originated here during

this time and then used in the temples in the region of Karnataka, Andhra

Pradesh widely as a feature of Mandapa. This temple marks an important

experimentation in the shape of the temple without compromising the functions

of the spaces.

Durg

Temple, Aihole, Karnataka.

Durg

Temple, Aihole, Karnataka.

The temples at Aihole establish a few developments in spaces like establishing

the plan of a temple as Garbhagriha, Antarala and mandapa as basic components

of temples, kakshasana at mandapa and temples as kalyanmandapa which is a place of celebration. This is also

supported by the inscription stating the same and also the fact that

decorations on columns are the way it would be done during festivals or

celebrations. This also establishes the roles of the temples as cultural spaces

for the settlement.

These structures were the beginnings of the movement which would result

in the rise of magnificent structures all over the country.

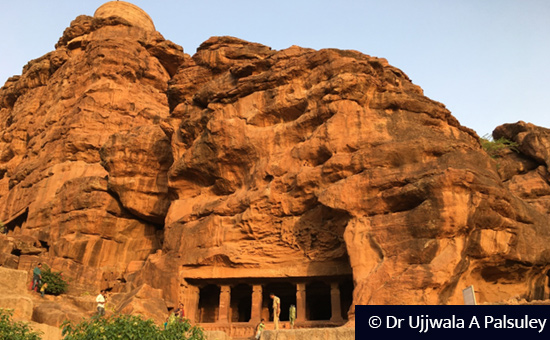

Badami Cave temples, Karantaka, India.

Badami Cave temples, Karantaka, India.

Read About Chalukyan Masterpieces of Badami, Aihole, Pattadakal

At this time around, there are also a few experiments in cave temples. A

few great examples are from Badami, and later in the southern part of India at

Mamallapuram.

These monolithic cave temples at Badami, also show the development of the

plan of temples. These are also very rich in sculptural expression, their

perfection of carving on the ceiling, walls, and pillars, and the perfection in

the dimensions of the temple elements, which must have been a tough task

carving it out from the piece of the mountain!

Cave temple at Badami.

Cave temple at Badami.

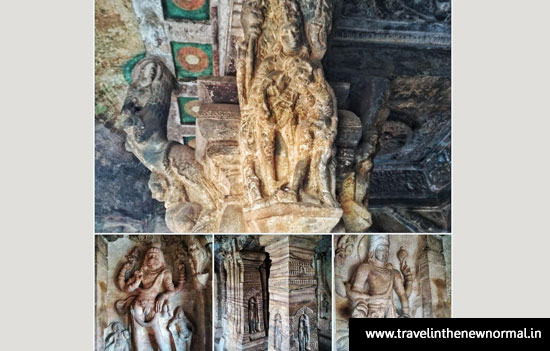

Badami – Interior of Maha Vishnu cave temple.

Badami – Interior of Maha Vishnu cave temple.

Sculpture

rich interiors of cave temples. Some are adorned with fresco paintings on the ceiling.

Sculpture

rich interiors of cave temples. Some are adorned with fresco paintings on the ceiling.

This cave temple is on a high platform with a stepped entry. It leads to

a rectangular space or mandapa with equidistant columns with intricate

carvings. At the centre, a small level is raised in a circular shape to define

the central space of Mandapa. Levels

with negligible raises are created to define the space between the mandapa and

nandi mandapa or antarala. Each inch of the ceiling is also carved with various

motifs and images. Small antarala can be seen with the change of level in the floor,

a doorway to the garbhagriha. Garbhagriha is raised at a considerable height,

with multiple steps leading to a smaller space, where only a shivlinga or a

deity could be placed.

Considering the rock-cut method of carving these caves out of the rock of

hills, these details demand special attention. It is to be noted that the

masons have carved these starting from the front to back getting each detail

with desired precision. These details indicate their clarity of design and

details even before the work started. The light quality changes from

outside till Garbhagriha, can be observed in the details also. Door jambs of

the Garbhagriha are carved, though the sunlight hardly reaches to this place.

In the times to come, there are developmental examples in southern India

at Mamallapuram which has a monolithic temple known as Pancharatha- a group of 5 temple

prototypes, and other cave temples from the 7th century. The Pancha Ratha demonstrate

the prototype of the temple forms.

Interestingly, the temple forms also show the two-storied temple as well.

The stone carving of the temple structure and iconography are significant

examples of the temple form development. Inscriptions on these temples give us

an account of the political, social and cultural details of the period.

Five Rathas Mahabalipuram, Tamil Nadu. Made in the 7th

century.

Five Rathas Mahabalipuram, Tamil Nadu. Made in the 7th

century.

Shore temple,

Mamallapuram is the next stage of temples which is one of the first structural

temples in this region and was built by Pallava king Rajasimha in the 8th

century A.D. The

site of Mamllapuram has many cave temples, dedicated to various deities,

showcasing the understanding of the iconography and its intricacy in carving

the images to the minutest of the details. With this context, when one looks at

Shore temple, dedicated to Shiva, it is one of its kind as this is an attempt

to construct a temple using the natural topography as well as bringing stones

to the site to have the desired temple form. The shikhara of the temple is a precursor

of Dravida Vimana.

Shore temple, Mamallapuram.

Shore temple, Mamallapuram.

The lineage of the mighty temples at Khajuraho, Dilwara, Lingaraja, Thanjavur,

and Kanchipuram can be traced to these varied experiments with the magic of

stone. The gradual development of various elements of the temples, keeping the

concept of Devalayam intact seems to be a constant phenomenon. The interaction

between the regions, influenced by the political changes, can be seen through

the temple designs.

Some believe that the Padavali Temple in Morena near

Gwalior was a precursor to Khajuraho. So also the Kailasanatha Temple at Kanchipuram is said to have inspired the Big

Temple at Thanjavur.

Over the period, three prominent types of temples emerged in Indian

temple architecture as Nagara

(Northern India), Dravida (Southern

India) and Vesara (Karnataka region).

There are some regional variations as well. The temples like Kandariya Mahadeva

and Lakshmana temples at Khajuraho, Lingaraja temple at Bhubaneshwar and Sun Temple

Konark are some of the remarkable examples of Nagara style. Similarly, included

in the Dravida style are Vaikuntha Perumal temple at Kanchipuram, Temples at

Madurai, Srirangam, Rameshwaram and Brihadeshwara at Thanjavur. The temples

like the Hoysaleshwara temple and Channakeshawa temple constructed during the Hoysala

reign showcase a few perfect examples of Vesara style.

These later temples have more elaborate plans which have multiple

functions around the Garbhagriha or vimana of the temple. The addition of

multiple mandapas, prakara, spaces for rituals, open mandapas and platforms is the

outcome of the sociocultural changes. Though

the temples have similar spaces, each temple has a unique character or feature.

The detailed study of each of the temples would reveal the uniqueness of the

temple. Ancient names of the temples, the stories carved on the temple, and idol

of the deity, physical features of the temples, can be closely observed to

understand the nuances.

Brihadeeshwara Temple, Thanjavur.

Brihadeeshwara Temple, Thanjavur.

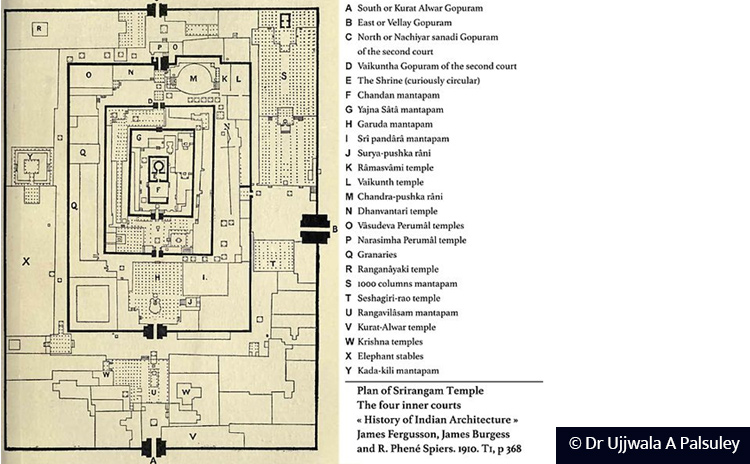

Plan of Shri Ranganatha Swamy temple at

Srirangam.

Plan of Shri Ranganatha Swamy temple at

Srirangam.

Gopuram of Srirangam Temple.

Gopuram of Srirangam Temple.

4. Conclusion

From the Sarasvati civilisation till about the 16th Century, the material evidence shows that the temple has gone through a transformation for its space articulation. The evolution from single space structure to the largest temple in India- Brihadeesvara temple of Tanjavur, and Angkor Wat temple in Cambodia, many variations of temples was a complex process. The archaeological discoveries across many parts of the world confirm the spread of this influence.

The temples also evolved from a more private space to a multifunctional

cultural and administrative centre. Hence, temples

became larger and the centre for administrative, economic, cultural, and educational functions. Other important aspects of people’s life revolved around the temples. There are also a few cities developed around the temples like the largest living temple at Srirangam.

The physical features of temples like material, climatic region, political,

social, and geographical influences guided the regional variations. They used

local construction techniques, materials, and local craftsmanship. However, the

principles of construction were from ancient texts and philosophies. The specific

iconography has been guided by symbolism since ancient times. Each region derived

its local terminology for temple parts, nomenclatures, and tales to tell. They

were all rooted in the temple tradition and the needs of society.

When one tries to decode the concept of the temple concerning the

architectural features using the present-day streams of knowledge available, it

seems more complicated due to the lack of many references which are lost in the

last few centuries of invasions. It needs an understanding of many subjects to

arrive at a holistic understanding of the temples. As stated by Kapila

Vatsyayan, in Kalatatvakosa- the

Indian Arts have been largely studied in isolation, with much emphasis being

given to chronologies and stylistic analysis along Western Lines.

Various professionals from allied fields have studied the temples with

their perspectives, but independently. The meaning and the interdependence between the arts and other disciplines have received relatively less attention. Literary and art-historical studies have rarely been combined, to do justice to both. Considering the complexity of the whole process of temple construction, it is significant to understand the process and the ‘meaning’ with which the temples were constructed.

The author is a

Conservationist, Architectural historian, Author, Ph. D. in Dravidian and Khmer

temple Architecture, Cambodia and the Founder of Samrachanā - Heritage

Conservation & Research Initiative, Pune.

References

& bibliography

1.Aasen, Clarence. (1998) Architecture

of Siam- A cultural history interpretation. Oxford University Press

2. Balfur, Edward (1857). The

Cyclopaedia of India and of Eastern and Southern Asia. Akademische Druck- u.

Verlagsanstalt. p. 105.

3. Briggs, L. P. (1999). The

Ancient Khmer Empire. Thailand, White Lotus publications

4. Coedes, George (1968). The

Indianized States of Southeast Asia. Honolulu: East-West Center Press.

5. Coomaraswamy A.K. (1972). History

of Indian and Indonesian Art. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal.

6. Dagens, Bruno. (1995). Angkor:

Heart of an Asian Empire (New Horizon) - Hames & Hudson Ltd

7. David, G. Marr; Anthony

Crothers Milner (1986). Southeast Asia in the 9th to 14th Centuries.

Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore.

8. Dhaky, M.A. (1996).

Encyclopaedia of Indian temple architecture- South India. Vol-I, Part 3.

American insititute of Indian studies, New Delhi: Pradeep Mehendiratta

9. Dumarcay, J. and Smithies,

M. (1995). Cultural sites of Burma, Thailand & Cambodia. Oxford

University press

10. Fergusson, James and

Burgess, James. (1876). History of Indian and Eastern Architecture, Nabu

Press

11. Fletcher, B. (1999). History

of Architecture. CBS publisher

12. Grover, Satish (2004). Masterpieces

of Traditional Indian Architecture, Roli Books

13. Grover, Satish. (1980). Buddhist

and Hindu Architecture in India. CBS publishers and distributers pvt ltd.

14. Hall, D. G. E. (1981, 4th edition) A History of South-East Asia. New York: St. Martin's Press.

15. Havell, E. B. (1918). The

history of Aryan rule in India From the earliest times to the death of Akbar. George

G. Harrap & Co ltd.

16. Hardy, Adam. (1995).

Indian Temple Architecture: Form and Transformation : the Karṇāṭa Drāviḍa

Tradition, 7th to 13th Centuries. Abhinav Publications

17. Higham, Charls. (2004). The

civilization of Angkor. Weitenfell and Nicolson, London

18. J. F. Staal, (1963). "Sanskrit and Sanskritization," JAS XXII.

19. Kramrisch, Stella. (1976).The

Hindu Temple, vol. I, Delhi

20. Kulke, H. (2001 Reprinted).

Kings and Cults (State Formation and Legitimation in India and Southeast

Asia. New Delhi : Manohar

21. Krishna, Deva.1995. Temples of India. Aryan

Books International Vol i& ii,

22. Majumdar, R.C (1991). Hindu

Colonies in the Far East. Calcutta: Firma KLM Private Limited

23. Majumdar, R.C. (1994) Ancient

Indian Colonisation in South East Asia, H. Santiko, Technological Transfer in

Temple Architecture from India to Java, in: Utkal Historical Research

Journal, Vol. V.

24. Nagaswamy, R. (2010). Brhadisvara

Temple: Form and Meaning. Aryan Books International.

25. Pichard, Perry. (1995). Tanjavur

Brihadisvara An Architectural Study. Indira Gandhi National center for the arts & Ecole Francaise D’Extreme-Orient.

26. Srinivasan, K. R. (1972). Temples of South

India. New Delhi: National book trust.

Also read

1. Six days of Indic Heritage in Cambodia

2. Shore Temple Album

3. Srirangam Temple album

4. Kandariya Temple Khajurao album

5. Brihadesvara Temple Thanjavur album

6. How did Hindu temples evolve

To read all articles by author