- Akanksha, co-founder of Center for Embodied Knowledge, tells the story of how four young men have come together to do workshops on decolonisation for urban Indians using India’s indigenous knowledge traditions.

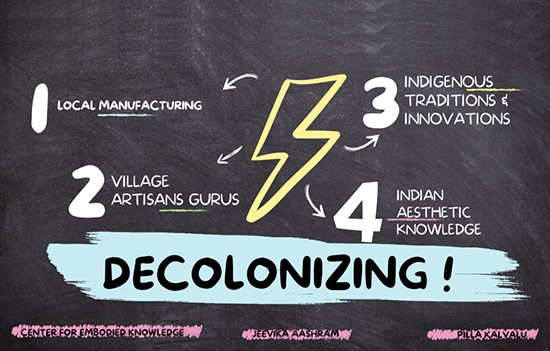

Decolonisation - A term most of us use these days across sectors,

professions, ideologies. Decolonisation of language, politics, law, symbols,

names. As this unfolds, is there a space

for decolonisation of Indian Aesthetic Knowledge? If you ask Pilla Kalvalu

they will grin and tell you, “… that is elementary, fundamental.”

Four young friends have come together to energise this decolonisation wave

using indigenous embodied practises, and creatively educate folks like

themselves: urban, English-educated Indians. Meet Dheeraj, an indigenous

architect. Mayank, a self-taught organic farmer. Dixit, a wildlife and forest

ecology enthusiast. And, the communication sutradhar, Aryaman.

Learning, even as they teach, they call themselves Pilla Kalvalu - Little

Streams - aiming to decolonise and learn from the still thriving indigenous

aesthetics and manufacturing, village artisans, and the indigenous traditions

and innovations of India.

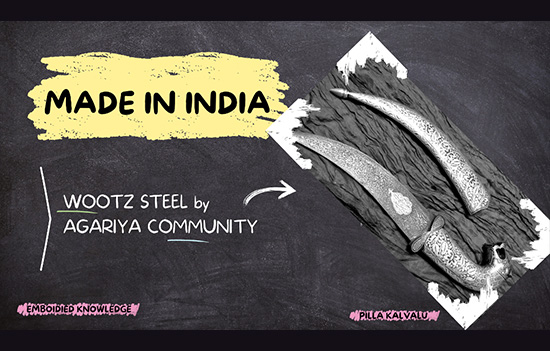

When the East India Company took over the

administration of Bengal in 1757, India commanded a quarter of world trade. The

fine muslin, chintz and calico cloth of the Indian weavers were prized from

Europe to East Asia. The homemade wootz steel of the Agariya community was the

highest quality steel available in the international market and used in the

highly refined products of Britain and Japan.

Under British rule, Indian weavers had their thumbs

chopped off. The Agariya community was declared a criminal tribe. The resources of India fuelled the Industrial Revolution in Britain and over time, the East India Company came to control half of the world’s trade.

There was another way by which indigenous manufacturing was undermined. Not only were the artisans made to suffer for practising their trade, but the patronage network which sustained their economy was slowly undermined. One way of doing this was by changing the habits of the Indian elite.”

With this English education came a free gift, an attitude of inferiority: ‘Made in India is inferior to that Made in England’. Clothes, Culture, Customs etc all. This attitude, the Pilla Kalvalu believe, lingers on even now.

“Today the Indian elite consumes standard sized plastic clothes mass manufactured by fast fashion brands from abroad while the weaver and tailor languish without work, or at best cater to the less educated who have not yet caught on to the fashion. There are noble initiatives trying to reverse this situation, but their biggest headache is consumer education.”

In their own unique way, groups like Pilla Kalvalu are a part of this

reversal. They have been conducting embodied workshops in Tamil Nadu and Madhya

Pradesh for urban Indians across age, temperament and professions. The residential workshops involve engaging with a variety of embodied

skills like indigenous architecture, farming, spinning, cooking, basket making,

pottery etc. They are learning essentially from the earth, Bharat-bhoomi,

literally.

Earlier this year they facilitated a workshop on Culture and Ecology in

collaboration with Jeevika Aashram, near village Indrana, Jabalpur (Madhya

Pradesh) where the teachers were all rural artisans, and the students all urban

- Indians or from other countries already working on alternatives in various

fields.

“In India, each villager is an artisan. And these are no ordinary artisans. Every artisan possesses a deep logical and aesthetic knowledge of materials, human interface and ecology. It takes years to be called an artisan, and then more to become a master. These are the artisans who brought in the riches to India before colonisation. And their craft, even now, commands a high price when presented appropriately …”

Indian Embodied Knowledge Traditions

The indigenous traditions the participants were engaging with involved

knowledge that is not confined to text or word alone. It involved, not just the

intellect, but the entire body-mind-sense complex.

They spent time with the artisans of the village, learning various crafts,

deep knowledge systems in themselves: Pottery, bamboo weaving, broom making,

spinning. They walked in the forested hills, guided by a local shepherd with

his unique knowledge of pastoral knowledge. They participated in the rituals and

festivities of the village

Transmitted orally this indigenous knowledge tradition encouraged them to

walk with their feet, work with their hands, and absorb with all their senses

before processing it in the mind, and only then, later, give it words.

Some of the embodied knowledge traditions the workshop participants engaged

with are Pottery, Bamboo basket making, tailoring, broom making, black smithy

and spinning. They learnt, immersing themselves in the village and household

ecology of the artisan-guru.

For embodied knowledge is not about ‘targeted learning’: pick up a skill and you are ready to go into production, no. Embodied knowledge is as much about the larger subtle-culture around the skill. The non-working time when jokes are cracked, tea is sipped and laughter happens. That’s when, the knowledge, slips in and becomes one with the learner.

Presenting a few glimpses from this unique knowledge-transfer that happened

during this five day immersive workshop held at the Jeevika Aashram, Indrana, Madhya

Pradesh.

1. Indigenous Pottery Knowledge

The participants are served tea as they sit around the potter-guru, Dassu. He comes from a long lineage of potters, “My grandfather taught my father, my father taught me, this is how the lineages of knowledge transmission have carried on.”

They observe him working closely for some time. After a while, he asks them

if they would like to try. Soon there are broken pots strewn all over. A crowd

of neighbours comes to watch the drama. Every time a pot is broken, Dassu gives

a wicked look and says “Bas thoko, mitti apne aap jud jayegi!” (Just beat it, the clay will come together on its own!)

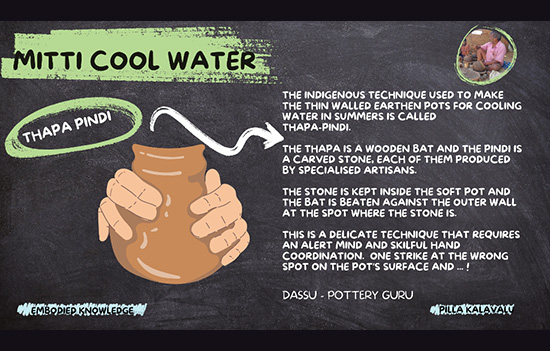

Knowledge Tradition: Cool Water from an Earthen Pot

If you have ever tasted the fragrant and cool water from an earthen pot,

you will know how harsh and tasteless the chill of refrigerated water feels.

The indigenous technique used to make those thin walled earthen pots is called thapa-pindi.

This requires a special knowledge and skill, getting rarer each day.

Dassu is one of the last potters in the village to practise the thapa-pindi

technique. The thapa is a wooden bat and the pindi is a carved

stone, each of them produced by specialised artisans who also are becoming

harder to find.

The stone is kept inside the soft pot and the bat is beaten against the outer wall at the spot where the stone is. This is a delicate technique that requires an alert mind and skilful hand coordination. One strike at the wrong spot on the pot’s surface, and it will break open.

Barter Economy

Dassu is preparing a set of seven pots for each house under his clientele for Akshay Tritiya. The pots are of different kinds, some for pouring water in the pooja, others for storing drinking water. In return for his pots - Pilla Kalvalu tells us - Dassu will not get money. Instead, he will get sacks of wheat which is in harvest. More than enough sacks for his family’s consumption, so the excess can be traded for his other requirements, “This is the last vestige of the practice of patronage from the old economy. The other artisans deal in cash now.”

2. Indigenous Bamboo Knowledge

Halke - the guru of bamboo basket making - asks sharply, “What do you want to learn from me?” His hands are fast, his eyes are keen and his demeanour is that of a much matured practitioner: humility, mixed with a beaming respect for his craft.

A master of the subtleties of craftsmanship, he teaches the participants how to hold the tools, how to handle bamboo and its various forms, what postures make it easier to work, how to weave so that the strands don’t come loose.

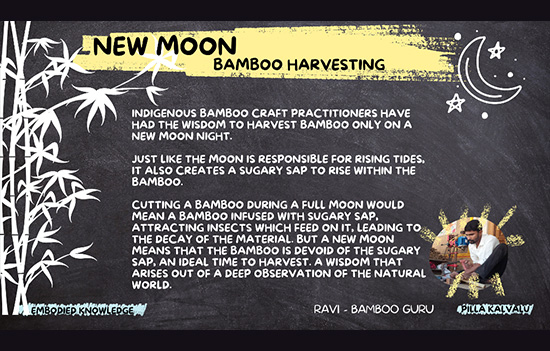

Meanwhile another Bamboo crafts guru, a young man in his 30s, Ravi is

teaching the participants how to make bamboo recliners. On the very first

meeting he tells them how craft practitioners had the wisdom to harvest the

bamboo only on a New Moon night. There is a logic behind that.

Just like the moon is responsible for rising tides, it also creates a

sugary sap to rise within the bamboo. Cutting a bamboo during a full moon would

mean a bamboo infused with sugary sap, attracting insects which feed on it,

leading to the decay of the material. But a new moon means that the bamboo is

devoid of the sugary sap, an ideal time to harvest. A wisdom that arises out of

a deep observation of the natural world.

Ravi only speaks when he stops using his tools. Once his tools come in

contact with the material, a manic focus follows.

When the participants get to try their hands on making different products,

they often find themselves losing patience, leading to the bamboo getting

damaged.

Observing their impatience, Ravi reminds them, “Every master was once a fool. Patience is your friend it should be deploy generously. Nothing can be mastered in a single day”

The five days of bamboo basket making with Halke has led to the realisation

that five days is a short time to learn the skill, but it is enough to get an

idea of the endless depths of knowledge in the craft. Four or five kinds of

weaves go into the making of their baskets and each basket turns out to be

unique without any of the participants knowing it. “Similarly, our bamboo fans are different from one another despite using the same techniques. Every pair of hands offers something different to each material.”

In a world of highly mechanised processes, Halke sticks to traditional

techniques of weaving without using nails or glue in his craftworks.

“As we sit with our baskets and he sits splitting thin bamboo strands for us, silence, whispers, stories and laughter merge. His eyes widen when we name our far-off cities and towns. Stories don’t distract him from the work at hand. One misstep and he knows it.”

Halke makes each commodity according to the needs of his individual buyers.

Apart from the basket and the fan, he also shows the participants a machaliya

- which is traditionally used by farmers to carry paan around with

them. In return for a machaliya, the farmers give him a sack full of wheat.

3. Art of Broom Making

Traditional brooms used in the village are made with palm leaves. The

Valmiki community is responsible for the cleanliness in the village. The

participants head to Anuj, a young 18 year old member of the community to learn

the art of broom making from him.

Anuj is a worshipper of Lord Hanuman, and has begun fasting every Tuesday.

He regularly goes to the Hanuman Mandir near his home, “Hanuman ji ki pooja sab se saral hoti hai, use koi bhi kar sakta hai. Isliye wo sab ke bhagwaan hain.” (There are no complicated ritual involved in worshipping Hanuman ji. Anyone can do that. That is why he is God for everyone.) Through all his growth pains, Lord Hanuman is

his guide.

To avoid conflict, each family has been allocated its own territory from where they are allowed to collect palm leaves. When the tree is on someone’s land, they may have to pay them some money. And each time, they begin plucking the leaves, the family asks the tree for permission to take its leaves.

Once plucked, the leaves are left to dry overnight. Then begins the process of shaping the leaves into the broom. While other broom makers use plastic rope to bind the broom, Anuj’s family use the metal wire instead. This tweak, they say, gives their product an edge, and so they never have to worry about selling their stock.

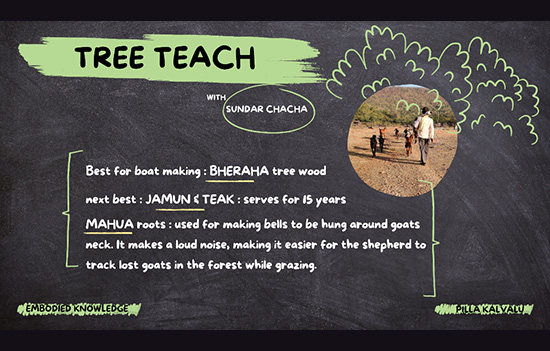

Wandering through the Village

The participants wander the village studying its architecture, its

lifestyle, getting an understanding of other knowledge traditions like

tailoring, black smithy and spinning. Sundar Chacha from the Barman community

takes them on a forest walk. He shows them the sacred groves. Teaches them

about fishing, boat making, shepherding and helps them identify nearly 20 tree

species.

The evenings are spent in discussions on various learnings connected with

the workshop. For instance, an Indian understanding of city & villages, how

it is different from that learnt from the western-modern notions; on difference

between artisanal and industrial modes of production; what wealth was in the

old economy and how it is understood in the new economy.

The discussions acquire another depth when the participants witness Tambura Baba’s (Jugraj Singh) songs on puranas. He is one of the last of his

tradition in the nearby villages. The Tambura is made with pumpkin, bamboo,

leather and wire - all locally sourced and made by Jugraj himself. Most of the

instruments used by musicians in the area are similarly made of locally

available materials.

Little Streams of Hopes

These workshops come with a vision that learning can happen independent of

western institutions that today monopolise learning. The ordinary villager who

has been dismissed as backward, somebody to be rescued, is actually a

civilisational elder, to be seen as a Guru. Those of us who have achieved

degrees may have missed out on some crucial education because we never saw our

own knowledge cultures.

"It is in villages like Indrana that the last vestiges of the pre-colonial patronage oriented economic system can be experienced. These workshops are not merely immersive experiences for the city bred. They are designed to learn from this still living system and acknowledge its importance. Fragments of this old way can still be found even in the big cities. These are the pieces from which the work of rebuilding a decolonised economy can be sparked.”

A short film (8mins) on the

workshop can be seen here

All photos by Pilla Kalvalu, Illustrations by the author. CEK has supported this workshop amongst many others.

Pilla

Kalvalu consists of four friends as of now all have been mentored by Dr Aseem Shrivastava. The Culture & Ecology

workshop was hosted by Jeevika Aashram

To read

all articles by author

Also see

1. Album

Hand Pottery making, Assam

2. Album Bastar

Craft making

3. Album

Pottery making Kutch

4. Album

Block Printing Sanganer