- This photo

feature by art historian Benoy K Behl tells you about Sanchi Stupa, including

its sculptures. It has o/s pictures with detailed captions. Some images are found

in churches of Spain and Portugal, captions have the details.

An earlier

article Who Made Sanchi Stupa. Text

and Photographs by Benoy K Behl

The

Sunga and Satvahana periods

Between 185 and 73 BCE, during the rule of

the Sunga Dynasty, foundations were laid for the rich traditions of art of the

Indian subcontinent. The harmony and interrelatedness of the whole of creation

became the underlying theme of all art. This is best represented by the

continuous, undulating vine of life, from which springs the bounty of nature,

the numerous forms of the world around us.

The forms of the world were sculpted on

the railings and gateways around stupas. These vedikas and toranas

separate the mundane, day-to-day world from the sacred space, at the centre of

which is the stupa. These sculptural representations help us to appreciate all

forms of life in their true perspective, as reflections of that formless

eternal, towards which we must proceed. Beyond the railings and gateways a

profoundly simple representation, a stupa, points out the Truth towards which

we must strive, leaving behind the forms and attractions of the world.

Another tradition that was clearly

established at this time was that of the indirect royal

patronage of all sacred monuments, which lasted through most of the ancient period. No king patronised the making of such edifices dedicated to any faith. However, they provided revenues to all faiths, for the upkeep of these establishments and for the monks and bhikshus gathered there. The earliest Buddhist art, with themes from the Buddha’s life and Jataka stories, was made under the rule of the Sungas. Sunga rulers generously endowed the revenue from many villages for the running and maintenance of Buddhist places of worship.

Sanchi

Stupas

The city of Vidisha, present-day Besnagar in Madhya Pradesh, was on the trade route which connected the plains of the Ganga to the Western Coast. It was also a great market place, at the centre of the vast and fertile plains of Central India. Among the earliest objects to be found here is a large stone pillar with an inscription, dated between 120–100 BCE. It was set up by a Greek devotee named Heliodorus, in honour of Vasudeva,

another name of Lord Vishnu.

At Sanchi, on a low hill next to Vidisha,

are the finest surviving early Buddhist stupas. Halfway up the hill, is a stupa which contains the relics of prominent Buddhist

teachers of the Mauryan period. The Vedika made around the stupa dates

to around 100 BCE. The Vedika has medallions and half-medallions which contain

sculptural relief. Corner pillars at the entrances are fully carved. The deity

of prosperity and abundance Lakshmi is seen with elephants pouring water over

her. The panel is carved in shallow relief and the style is similar to that of

Bharhut.

The greatest surviving Buddhist stupa of

the BCE period is on top of the hill at Sanchi. It is likely to have enshrined

the relics of the Buddha. The stupa was originally made in the third century

BCE. There is an Ashokan pillar at the southern entrance of the stupa. In the

middle of the second century BCE, it was doubled in size and its previous wooden Vedika was replaced with a massive stone

one.

By the end of the first century BCE, the

Satavahanas, kings of the Deccan region, extended their rule to Central India. Major stone renovations that were carried out during

their reign made this stupa one of the most significant of all Buddhist

monuments. Four gloriously carved stone Toranas, 34 feet in height were

made. They were completed in the first century CE. The traditions of art

established during the time of the Sungas became more sophisticated in these

magnificent Toranas, made in the time of the Satavahanas.

The carvings were a result of the

donations by the people of Vidisha, a fact revealed by the 631 inscriptions on

the toranas. The donors included gardeners, merchants, bankers, fishermen,

housewives, householders, nuns and monks. Interestingly,

almost half the donations were made by women.

The massive Vedikas are plain and without

carvings. The Toranas have two upright pillars, which support three horizontal

bars or architraves. On the east and north Toranas, between the pillars and the

architraves, are superbly made elephants, sculpted almost completely in the

round. The west gateway has Ganas or dwarves. The one on the south has Lions.

The Ganas are shown with rolls of fat and

vast bellies which bulge over their dhotis. They have individualized facial

expressions. Ganas continued as a favourite motif

of the Indian artist, in the centuries to come. They deepen the sense of

the reality presented in the art, where the humorous and the sublime co-exist,

reminding us that everything has its place in existence. In later times, ganas

become an integral feature in Shiva temples.

The veneration of nature’s fertility and abundance, as seen at Bharhut, continues here. Twenty-four auspicious Yakshis are made as bracket figures on the gateways. On the east Torana is a beautifully-made Yakshi who holds the branch of a mango tree above her. The notion of the creative vitality of nature and its fruitfulness is convincingly portrayed. Though she is physically attached to the matrix, she is sculpted as though fully in the round. Details, seen from all possible angles, including the rear, are carefully articulated.

As at Bharhut, male figures are made

guarding the entrances to the sacred stupa. One figure is in Indic garb, a dhoti and turban. Another wears Greek

garments and carries a foreign-type shield and spear. It may be noted

that, in early Indian art, soldiers are generally depicted as foreigners.

The reliefs on the Toranas depict

incidents from the Jatakas, as well as events from the life of Gautama Buddha. The focus is still not on the personality of the Buddha,

who is represented by symbols. The wheel represents the first teaching

of the Dharma; the Bodhi tree represents Enlightenment; while footprints and an

umbrella over a vacant space proclaim the presence of an Enlightened One.

The Toranas of the stupa at Sanchi present

a view of the overflowing activity of life. The pictorial setting of the

narratives richly reflects contemporaneous town and village life. These reliefs

at Sanchi are the most important visual record of the architecture and

lifestyles of the period. Stylistically, the Sanchi reliefs display a greater

sophistication than the ones at Bharhut. Whereas single figures were made at

Bharhut, here there are large groups of many figures. Men, women, children and

animals are shown in a variety of poses and in the midst of exuberant life.

They are no longer depicted only frontally: instead, three-quarter profiles are

also seen. The Sanchi artist also depicts a wide range of expressions

effortlessly.

The Sanchi artists utilized multiple

perspectives and viewpoints. This allowed them to present that view through

which the object or person was most easily recognised. Events that occurred and

figures that are in the distance are represented in the upper part of the

panel, while those figures which are closest to the viewer, are shown in the

lower section. The technique of receding perspective is not employed here. All

elements which are considered important are presented large and in clear

detail. Another feature of Indian art seen from earliest times is that the

leaves of a plant or tree were large, so they could be recognized.

There is an inscription on the eastern Torana

of the stupa which mentions that the exquisite carvings on the toranas are the

work of ivory carvers of Vidisha.

Indeed, the stone is so finely carved here that it reflects the care and

detail of work on delicate ivory.

A smaller stupa at Sanchi contained the relics of the Buddha’s close disciples Modgalyana and Sariputra. The only torana here was also made under the supervision of the Satavahanas in the first century CE. As in the earlier stupas, the sculptures present a vision of the world which sees the unending rhythm in all of creation. There are numerous representations of Purnaghatas, or ‘vases of plenty’, from which come forth the joyous forms of the world. The vine of creative blossoming moves with a pulsating life through the Vedika. It brings to us the natural order in its myriad forms: flowers, fruit, animals, humans and composite creatures.

These are traditions which continued in

Indian art in later times and spread far and vide, beyond the shores of India. Purnaghatas, with pillars rising out of them, as in

Buddhist caves, are seen in the early mosques and even sometimes in

contemporaneous pillars in Indonesia. All these motifs of the fruitfulness of

nature are depicted in similar form and in profusion in the early churches of

Spain and Portugal.

While the great stupas at Sanchi were

being built and carved in the plains of Madhya Pradesh, the Satavahanas and the Kstrapas ruled over the Deccan. They

encouraged and extended their benevolent patronage towards Buddhist establishments.

Scores of caves dedicated to the Buddhist tradition and numerous impressive

stupas were made during their rule, across the Western Ghats and the Deccan, in

present-day Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka.

We now feature pictures by author.

Stupa II, c. 100 BCE. Photograph by Benoy

K Behl

Stupa II, c. 100 BCE. Photograph by Benoy

K Behl

Made in Sunga times, the reliefs on the Vedika

of this stupa are among the oldest Buddhist art in the world. These depictions

continue the rich visual lore of the land and show the roots of the specific Buddhist

imagery to come in later centuries.

Composite Creature, Stupa II, Sanchi c. 100 BCE. Photograph by Benoy

K Behl

Composite Creature, Stupa II, Sanchi c. 100 BCE. Photograph by Benoy

K Behl

The depiction displays the oneness of all

life forms. It is such a delightful and

joyous creature, with the qualities of an elephant, cow, deer and even a

horse. All of creation is seen in a

vision full of warmth.

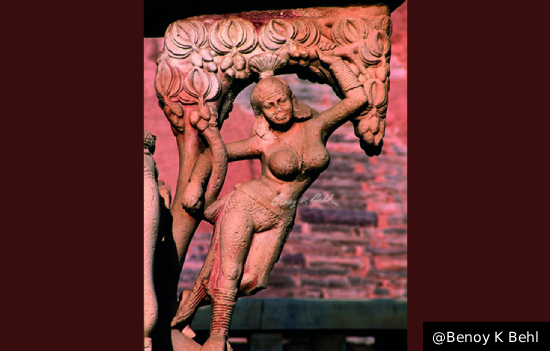

Shalabhanjika, East Gateway Stupa I, Sanchi first

century CE.

Photograph by Benoy K Behl

Shalabhanjika, East Gateway Stupa I, Sanchi first

century CE.

Photograph by Benoy K Behl

The best-known sculpture of the Sanchi

stupas is this exquisite shalabhanjika, who depicts fertility and abundance.

The Great Stupa, East Gateway, inner view, Stupa I,

Sanchi first century CE. Photograph by Benoy K Behl

The Great Stupa, East Gateway, inner view, Stupa I,

Sanchi first century CE. Photograph by Benoy K Behl

The Vedika creates a passage for the

circumambulation of the stupa.

Ganas supporting architraves, West Gateway Stupa I,

Sanchi, first century CE. Photograph by Benoy K Behl

Ganas supporting architraves, West Gateway Stupa I,

Sanchi, first century CE. Photograph by Benoy K Behl

Ganas are among the early images of Indian

art, which continue through all the ages. They deepen the reality conveyed in

the art, as the whole of life includes multiple aspects, from the humorous to

the sublime.

Detail, the unending vine of the natural life force,

South Gateway Stupa I, Sanchi, first century CE. Photograph

by Benoy K Behl

Detail, the unending vine of the natural life force,

South Gateway Stupa I, Sanchi, first century CE. Photograph

by Benoy K Behl

The art of Bharhut and Sanchi brings us

the unending vine, which carries the numberless forms of the natural world. The

Yaksha comes out of the undulating vine of life, carrying a garland. Out of his

mouth is again disgorged the vine of life, bringing forth the fruits and

flowers of the natural world.

Detail, Graceful Devas, Enlightenment Scene, West Gateway, inner face, Stupa

I, Sanchi, first century CE. Photograph by Benoy K Behl

Detail, Graceful Devas, Enlightenment Scene, West Gateway, inner face, Stupa

I, Sanchi, first century CE. Photograph by Benoy K Behl

This scene is one of the finest sculpted

at Sanchi, with gentle and graceful expressions on the faces of the figures.

These devas are gathered on the occasion of Enlightenment, to pay homage to Gautama

Buddha.

Detail, Vessantra Jataka, North Gateway, inner face,

Stupa I, Sanchi, first century CE. Photograph by Benoy

K Behl

Detail, Vessantra Jataka, North Gateway, inner face,

Stupa I, Sanchi, first century CE. Photograph by Benoy

K Behl

Prince Vessantra is a previous birth of

Gautama Buddha. In this Jataka tale, he exemplifies the quality of generosity.

He gifts everything that he has and was left with nothing.

Worship of Seven Buddhas, represented by trees, East

Gateway, Stupa I, Sanchi, first century CE. Photograph by Benoy

K Behl

Worship of Seven Buddhas, represented by trees, East

Gateway, Stupa I, Sanchi, first century CE. Photograph by Benoy

K Behl

The Seven Manushi Buddhas are the Buddhas

or Enlightened Ones of the world, of whom Gautama Buddha is one. As individual personalities were not as yet shown in

Indic art, they are represented here as trees.

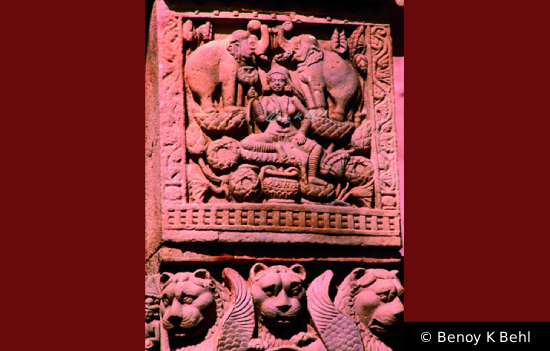

Lakshmi, deity of abundance and prosperity, with elephants pouring water

on her, East Gateway, Stupa I, Sanchi, first century CE. Photograph by Benoy

K Behl

Lakshmi, deity of abundance and prosperity, with elephants pouring water

on her, East Gateway, Stupa I, Sanchi, first century CE. Photograph by Benoy

K Behl

This is also interpreted as Queen Maya,

mother of Prince Siddhartha. From the earliest Sanchi stupa and the Bharhut

stupa onwards, one of the earliest deities we see

in Indic art is Lakshmi, who represents the abundance and riches of nature. Photograph by Benoy K Behl

Lord Indra with Vajra, Pillar of East Gateway, Stupa

I, Sanchi, first century CE. Photograph by Benoy K Behl

Lord Indra with Vajra, Pillar of East Gateway, Stupa

I, Sanchi, first century CE. Photograph by Benoy K Behl

Among

the earliest deities seen in Buddhist art is Lord

Indra. The vajra or thunderbolt which he holds in his hand, later became

the symbol of the Vajrayana school of Buddhism.

North Gateway, inner view, Stupa I, Sanchi, first

century CE. Photograph

by Benoy K Behl

North Gateway, inner view, Stupa I, Sanchi, first

century CE. Photograph

by Benoy K Behl

These magnificent gateways, carved on both

sides, are among the finest works of Indian art. The themes are carved in fine

detail remind us of the inscription which mentions that these reliefs were the

work of the ivory carvers of Vidisha.

Worship of stupa, pillar, North Gateway, Stupa I,

Sanchi, first century CE. Photograph by Benoy K Behl

Worship of stupa, pillar, North Gateway, Stupa I,

Sanchi, first century CE. Photograph by Benoy K Behl

As images of individual personalities were

not shown in Indic art at this early stage, symbols such as this stupa indicate

the Buddha in the art of Sanchi.

Detail, the unending vine of the natural life force, South Gateway Stupa

I, Sanchi, first century CE. Photograph

by Benoy K Behl.

Detail, the unending vine of the natural life force, South Gateway Stupa

I, Sanchi, first century CE. Photograph

by Benoy K Behl.

Yakshas are seen here, disgorging the

unending vine of the life of the natural world around us. The vine is continuous

and brings the forms and fruits of the world. The yakshas carry auspicious

flower garlands in their hands. This is a theme in

Indian art which runs through the ages to come. As we go to the stupa or

to the temple, we are constantly shown the illusory world of forms all around

us. This art is a remarkable lesson, which shows how the force of Maya or

Mithya creates the world of nature in which we live.

Purnaghata (vase of plenty), detail, vedika, Stupa II, c. 100, BCE. Photograph

by Benoy K Behl

Purnaghata (vase of plenty), detail, vedika, Stupa II, c. 100, BCE. Photograph

by Benoy K Behl

As in the case of the yaksha, the Purnaghata, or ‘vase of plenty’, has the life of nature coming out of it. This is one of the most common motifs in Indian art. Even the pillars in caves of the early period are seen rising out of such ‘vases of plenty’.

Composite creature, detail, vedika, Stupa II, c. 100, BCE. Photograph

by Benoy K Behl

Composite creature, detail, vedika, Stupa II, c. 100, BCE. Photograph

by Benoy K Behl

The oneness of all life forms is displayed

in these delightful creatures. Here we see the connectedness of the life of

fish, a bull and a crocodile. The creature spews out of his mouth the vine of

life and flowers, representing the vibrant life of the natural order.

Lion disgorging the vine of life, detail, fresco, Patio del Yeso,

Seville, Spain, late medieval period. Photograph by Benoy K Behl

Lion disgorging the vine of life, detail, fresco, Patio del Yeso,

Seville, Spain, late medieval period. Photograph by Benoy K Behl

This image is remarkably similar to the

themes of ancient Indian art which are seen everywhere in Bharhut, Sanchi and

thereafter. The lion disgorges the vine of life which moves all around him and

brings forth the blossoms of the natural world.

Spain and Portugal were under Arab rule

for about eight centuries, from the early eight century onward. This was the

period in which Western Europe imbibed many concepts of science, mathematics,

medicine, agriculture, art, literature, music, rational thinking and knowledge

of Greek philosophy and science, from the Arab rulers. This was the period

which transformed Western Europe. Much of what the

Arabs brought to Europe was Indian in origin, including Arabic translations of

the ancient Indian astronomer and mathematician Aryabhatta. In fact, the numerals of mathematics which the Arabs brought were called ‘Hindi’ by them, as they came from the Indian sub-continent.

Along with ideas of astronomy and mathematics, the Arabs must have been the carriers of the highly-developed motifs of ancient Indian art, which we see in the early European Churches, after the Arab influence. European art historians were not familiar with ancient Indian art and these thousands of representations have been called “pagan”. Actually, these are highly-developed

philosophical themes of ancient Indian art which appear to have travelled to

Europe with the Arab influence.

Composite creature, fresco, Patio del Yeso, Seville, Spain, late medieval

period.

Photograph by Benoy K Behl

Composite creature, fresco, Patio del Yeso, Seville, Spain, late medieval

period.

Photograph by Benoy K Behl

Thousands of such composite creatures were

made across the early churches of Spain, Portugal and Italy, showing a

remarkable similarity with the themes of ancient Indian art, from the second

century BCE onward.

Just like in the art of the Sunga period,

this creature shows a connectedness of all life forms, ranging from the plant

life seen below, snakes with wings, humans and finally the leaves which are

seen on his head. This figure would be termed a kinnara in Indian art. He also reminds us of the numerous naga-devas. The

endless vine of life is also seen on either side of him.

Doorway details, Convento De Cristo, Tomar, Portugal, early medieval

period.

Photograph by Benoy K Behl

Doorway details, Convento De Cristo, Tomar, Portugal, early medieval

period.

Photograph by Benoy K Behl

Here we see on the left a creature with

horns and a ferocious mouth, disgorging the continuous vine of life. He is made

just like the vyalas and yakshas in ancient Indian art, from whose mouth

emanates the stream of life. On the right, we see a vase, like the Purnaghatas

of Indian art, from which comes forth the treasure of the natural order.

Doorway, detail, Convento De Cristo, Tomar, Portugal, early medieval

period.

Photograph by Benoy K Behl

Doorway, detail, Convento De Cristo, Tomar, Portugal, early medieval

period.

Photograph by Benoy K Behl

To the side of the entrance to the

convent, we see a vase, from which comes forth the life of the natural world.

This is exactly the theme we see in the ancient stupas and temples, including

the easy contiguity which is presented between the animal and plant world.

Doorway, Convento De Cristo, Tomar, Portugal, early medieval period. Photograph

by Benoy K Behl

Doorway, Convento De Cristo, Tomar, Portugal, early medieval period. Photograph

by Benoy K Behl

It is amazing to see the representation of the ‘vases of plenty’, the vyalas and the continuous vine of life, carrying in it numerous creatures, joyously presenting the world of nature, in the carvings around the doorway. These are exactly the themes made at the doorway of ancient Indian stupas.

In later Indian temples of the ancient and

the medieval period, these themes are made in parallel bands which move around

the doorway, precisely as we see them made here.

To read all

articles by author Benoy K Behl

To see albums of

Buddhist Monuments

To read articles

on Buddha Vakhya