- This essay, with pictures, covers the architectural

expression of the Chola kings (period earliest times till 1000 A.D.) from the

remains of the temples in the southern part of India.

Introduction

Southern India has many ancient names Bṛhad-Drāviḍadēśa,

the land of the Dravidian-speaking people, Drāviḍadēśa in a narrower

sense, more frequently called Dammila or Dammiladēśa or the Cōl̤adēśa,

which refers to the present-day state of Tamil Nadu (TN).1 The next para briefly tells about the geographical boundary of

modern-day TN.

“The Madras Presidency, during the British, covered a vast expanse of the southern part of India that encompasses modern-day TN, the Lakshadweep Islands, Northern Kerala, Rayalaseema (Andhra Pradesh), Coastal Andhra, districts of Karnataka and various districts of southern Odisha.” Source A fast to draw attention to demand for a state of Telegu speaking regions of Madras resulted in the formation of Andhra Pradesh in 1953. In 1956 Madras was divided further, with some areas going to the new state of Kerala and other areas becoming part of Mysore. What remained of Madras state was renamed Tamil Nadu in 1968.” Source

Geographically, this region is outlined by the broad

coastal plains and narrower coastal belt on the west. It extends up to the Satpura-Ajanta

ranges to the north and Nilgiris to the south. The peninsular plateau has a

great network of rivers - the Godavari in the north, Krishna, Tungabhadra

and Bhima and the north Pennar or Pinakini. They flow towards the east

into the Bay of Bengal. Vindhya Mountains have always been known as the

southern limit of North India from historical times. It acted as a barrier for the

free movement from North to South. The southern part of India was thus comparatively

protected from invasions a bit longer that North India witnessed throughout

history.

The Cholas were looked upon as descendants of the

Solar dynasty. The Puranas speak of a Chola king, a supposed contemporary of

the sage Agastya, whose devotion brought the river Kavery into existence.

The imperial Cholas' history is discussed widely and their majestic temples are acknowledged as - World Heritage Sites of Living Chola temples. However, the early Chola kings and their architecture need attention to help one understand how this great dynasty evolved in the panorama of Indian architectural history.

This paper

focuses on the architectural history and temples of the early Chola period from

its earliest references till 1000 AD.

History of Early Chola rulers

The legendary early Chola kings have recorded the

history of early Chola rulers of the Sangam period in both Tamil and Sangam

literature. The other source of early Chola history is found in the

inscriptions left by later Chola kings.

The main source of information about early Chola kings is the Sangam literature – particularly, religious literature such as Periyapuranam which is a semi-biographical poem of the later Chola period which gives an account of the temple and cave inscriptions left by medieval Cholas.

The Early Cholas of the Chola dynasty existed during the pre and post-Sangam periods (600 BCE–300 CE). They were one of the three principal kingdoms of Tamilakam. Their early capitals were Urayur (Tiruchirapalli) and Kaveripattinam. Alongside the Pandyas and Cheras, the history of the Cholas dates back to a time when written records were scarce. The lineage of the Chola kings is documented in Tamil literature and some inscriptions by later Chola kings. These sources mention the names of kings for whom no verifiable historical evidence remains. There are many versions of this lineage.

Pillars of Ashoka (inscribed 273–232 BCE) inscriptions, mention the names of the three dynasties, Cholas, Pandyas, and Cheras, among the kingdoms, who were on friendly terms with him. The famous Hathigumpha inscription mentions the king of Kalinga, Kharavela, who ruled around 150 BCE, and his confederacy of the Tamil kingdoms that had existed for over 100 years.

Ancient Tamil Nadu contained three monarchical states,

headed by kings called Vendhar and several regions headed by the chiefs

called by the general denomination Vel or Velir. Still, at the

lower local level, there were clan chiefs called Kizhar or Mannar.

During the 3rd century BCE, the Deccan was part of the Maurya Empire, and from

the middle of the 1st century BCE to the 2nd century CE the same area was ruled

by the Satavahana dynasty. The Tamil area had an independent existence outside

the control of these empires. The Tamil kings and chiefs were always in conflict

with each other mostly over the control of land. The royal courts were mostly

places of social gathering and were centres for distribution of resources.

Karikala Chola was the most famous early Chola king. He was the son

of Ilan-cet-Cenni, the possessor of many war Chariots. The Pattina-p-palai, a long poem on the Chola seaport capital of Kaveripattinam, describes the courageous way in which the young Karikala escaped imprisonment and established his right over the throne. In the battle of Venni near Tanjavur, he fought against the combined attack of Pandya and 11 minor chieftains led by Cera's chief, the Velir.

The account of people, their occupations, social and religious life, places of

worship, trade and commerce etc. can be comprehended through this long poem. He

is also praised here for the irrigation works, for bunding and raising the

flood banks of the Kaveri River, for forming the network of irrigation

channels, and also for his remarkable construction of a Kallanai Dam across the

Kaveri River, near present-day Trichy.

Kallanai Dam, over Kaveri River by Karikala Chola.

Kallanai Dam, over Kaveri River by Karikala Chola.

He is mentioned in several poems in the Sangam poetry.

Purananuru poem - 224 mentions him as a great king who performed Vedic

Sacrifices. In later times Karikala was the subject of many legends found in

the Cilappatikaram and inscriptions and literary works of the 11th and

12th centuries.

Two other Chola rulers, who

are known and contributed significantly are Ilan-Cet-Cenni

and Cenkanan or Ko-Cenkat Chola. There were

great warriors, who captured forts of Ceras. Cenkanan was a great devotee of

Shiva and has been canonised among the 63 Saiva saints the Nayanars. He lived

around 4 or 5th century AD. According to the Tirumangai Alvar, a

later Vaishnava Saint, Cenkanan Chola built around 70 temples using bricks

along the bank of the river Kaveri.

Kocengannan was another famous early Chola king who has been celebrated

in several poems of the Sangam period. He was even made a Saiva saint during

the medieval period.

Typical hero and demi-gods found their place in the

ancestry claimed by the later Cholas in the genealogies incorporated into the

copper-plate charters and stone inscriptions of the 10th and 11th

centuries. The earliest version of this is found in the Kilbil Plates which

give fifteen names before Chola including the genuinely historical ones of

Karikala, Perunarkilli and Kocengannan. The Thiruvalangadu Plates expands this

list to forty-four, and the Kanya Plates lists fifty-two.

The spread of the Chola

kingdom during 5-6th AD was between the North Vellar, a little north

of Chidambaram in the south Arcot District, and the South Velar, 30 miles south

of Trichy, with the sea on the east and Kongu area of the Cera on the west. The

capital cities of the Cholas were Uraiyur on Kaveri near Trichy and the port

city of Kavery-p-pattinam.

During the end of 4th

AD till mid 6th century AD the power of Cholas came under eclipse

due to Kalabhra occupation of the larger part of Tamil Nadu.

Only after the defeat of

Kalabhras by Pallavas of the Simhavishnu line and the Pandyas under Kodungon,

in the second half of the 6th Century, the name of Chola chieftains reflects

in a few records occasionally. Before Vijayalaya Chola, came to the scene, Cholanadu

was ruled by the Muttaraiyars thought to be a remnant of the Kalabhra Clan. For

the larger part of their career, the Muttaraiyars remained as feudatories to

the Pallavas of Kanchi. What prompted Parakesari Vijayalaya to oust the

Muttaraiyars or where he may have been located before he became the lord of

Tanjai remains unanswered. The earliest inscriptions ascribed to Parakesari as

well as some grants issued by him and later reconfirmed by fresh charters of

his descendants support his historicity but curiously hint at western Tondinadu

as his original domain.

His relationship with Pallavas

is not known. There are a few assumptions about the matrimonial alliances of

his daughter with the Pallava king. From 864 AD and 878 AD, the Kaveri region

was again ruled by Pandyas, which is also supported by the inscriptions of this

period. How long Vijayalaya Chola kept his

territory is still unknown.

His son Aditya-I mentions his count to the throne from AD

871. It is known that he had firm control on Kaveri delta from AD 878. He

wished to recapture the ancestral territory of the Cholas. He consolidated the

Chola Kingdom and established friendly relationships with various kings. There

are no inscriptions of Aditya-I stating his temple construction activity. A few

inscriptions known of royal queens and princes are about the donations to the

temples. The Anbil plate of AD 961 by his grandson- Sundara Chola credits him

with the building of temples in stone dedicated to Shiva on both the banks of

Kaveri. A temple like Nageshwaraswami at Kumbhkonam seems to be a Royal temple,

for its richness of embellishment and excellence in workmanship.

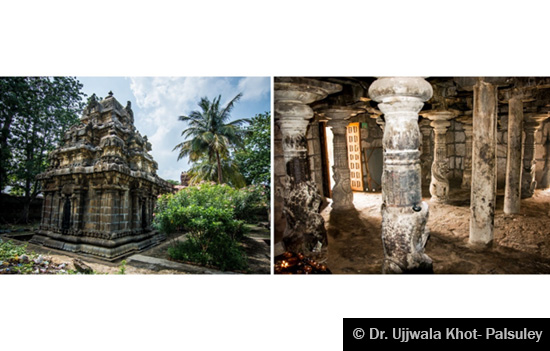

Nageshwaraswamy temple, Kumbhakonam

Nageshwaraswamy temple, Kumbhakonam

Temples of Early Cholas

Temples in Sangam literature are designated Manram of the Sabha Type, Kottam of Koshtha or Sala Type and Koyil, the royal residence, reminiscent of the corresponding Sanskrit Prasada to man both a temple and a king’s palace.

In early Tamil literature, the

temple is also called Madam, signifying a storied structure. The nomenclature Manram,

Kottam, Madam, and Nagaram may originally have indicated

architectural plans of temples, four-sided, curvilinear or polygonal etc.

These early structures may

have been brick and timber structures with tiled or timber roofs, or

mud-and-wattle thatch-roofed houses. The earlier descriptions of the cities

tell that Makar Torana gates and shikhara were reaching the skies. Walls were

of brick and mortar plastered with stucco and painted and supporting pillars

spanning beams, roof framework, doors and frames were of hard timber. These

were either carved or covered with embossed metal sheets.

The Ahananuru describes

the principal deity as painted on the hind wall of the sanctum of a temple. The

object of worship in a temple could be a mural painting painted stucco or

something even a carved and painted wooden plaque. This continued till the 7th

AD, when Pallava cave temples for the first time had images carved as stone

reliefs on the back wall after AD 680.

The earlier texts state that Nulari

Pulvar, Antanar, Asan and Perun-Kani and with artisans who were well

versed with canons, were consulted while constructing the temples.

Nageshwaraswamy temple, Kumbhakonam.

Nageshwaraswamy temple, Kumbhakonam.

Aditya-I died in Tondaimandalam,

where Parantaka-I his son erected a memorial

shrine later.

Parantaka-I captured the

region under Pandya Rajasimha-II and assumed the title of ‘Maduraikonda’. He conquered the Bana kingdom and also vanquished Vaidumnba a feudatory to Rashtrakuta, and assumed the title ‘Vira-Chola’. He guarded his frontier from Rashtrakuta by stationing Rajaditya between the rivers Vellar and Pennar.

After Parantaka’s death, Gandharaditya took over and ruled over till AD 957. Very few temples were built during Gandharaditya’s time. In the reign of Uttam Chola, particularly the queen mother- Sembiyan Mahadevi, made endowments to many temples and rebuilt several older temples in stone. She continued her religious activities for many years till the time of Rajraja-I.

During the early Chola times,

Shaivisam was predominant as a religion of the state. Vaishnavism was

considerably less important. Jainism at a few centres and Buddhism at

Nagapattinam had barely managed to survive.

Architectural features of Early Chola period:

Some general characteristics

of Chola temples by 10th C AD are:

1. The temple is enclosed within a compound wall called

Prakara.

2. The front wall has an entrance gateway in its centre

- Gopuram.

3. Consists of a square-chambered sanctuary topped by

a superstructure or tower- Vimāna.

4. The Mandapa, which always covers and precedes the

door leading to the garbhagriha.

5. The Vimana has its peculiar composition of small

modules of kuta-shala culminated at Stupi and Kalasa.

6. A large water reservoir or a temple tank enclosed

in the complex is a typical feature of temples.

7. Pillared halls/mandapas are used for many purposes

and are the invariable accompaniments of these temples.

Spatially, these temples show an axial alignment of

the Gopurams in the cardinal directions of the temple. This peculiar

arrangement of the temple is a characteristic of the Dravidian temple. The

temple tower is situated in the centre of the enclosure, with a series of

mandapas in front of the garbhagriha towards the entrance of the temple.

The ancillary deities are placed along the enclosure

wall, or in the courtyard between the enclosure and the main Vimana. Shiva

temples would have a Nandi Mandapa outside the first prakara and Gopuram,

sometimes having another wall enclosing this shrine.

Let us take an overview of the temples constructed

during the reign of Aditya Chola-I (AD 871-898-907)

Tirutantōrīśvara temple, Tirucirāpalli

Tirutantōrīśvara temple, Tirucirāpalli

Ōḍavanēśvara temple, Tiruccatturai.

Ōḍavanēśvara temple, Tiruccatturai.

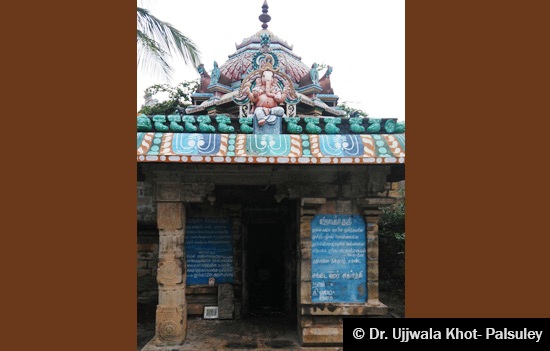

6. Puṣpavanēśvara temple, Tiruppanturutti

Vēdapururīśvara temple, Tiruvēdikuḍi

Vēdapururīśvara temple, Tiruvēdikuḍi

Āpatasāhyēśvara temple, Tiruppalanam

Āpatasāhyēśvara temple, Tiruppalanam

Pancanadīśvara temple, Tiruvaiyāru

Pancanadīśvara temple, Tiruvaiyāru

Agnīśvara temple, Tirukāṭṭupalli

Agnīśvara temple, Tirukāṭṭupalli

Agnīśvara temple, Tirukāṭṭupalli. Credit Temple Project.

Agnīśvara temple, Tirukāṭṭupalli. Credit Temple Project.

Agastīśvara temple, Maṇḍapa and Parivārālayas, Kīlaiyūr

Agastīśvara temple, Maṇḍapa and Parivārālayas, Kīlaiyūr

Agastīśvara

temple, Maṇḍapa and Parivārālayas, Kīlaiyūr

Agastīśvara

temple, Maṇḍapa and Parivārālayas, Kīlaiyūr

Dārukāvanēśvara temple, Tirupparutturai

Dārukāvanēśvara temple, Tirupparutturai

Dārukāvanēśvara temple, Tirupperunturai

Dārukāvanēśvara temple, Tirupperunturai

When one closely looks at the

temples from this period, a few architectural details are evident. Chola temples of early phase inherit the general

principles and forms from Dravidian architecture of earlier traditions, but

they also introduce certain innovations in plan, elevation and in anukāya

elements.

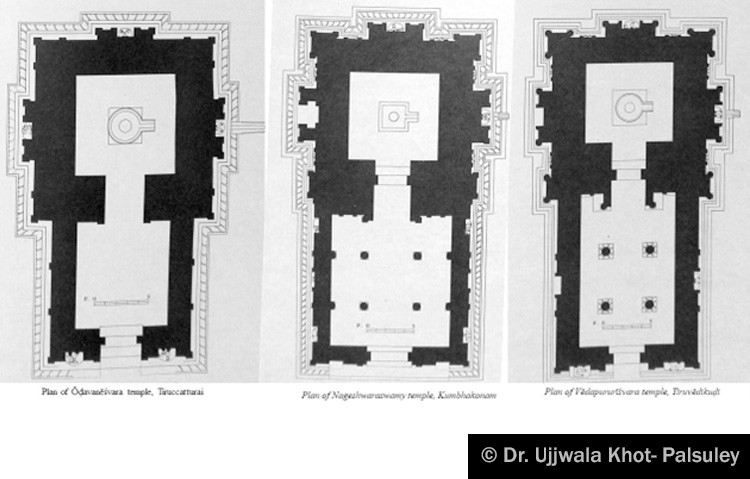

Plan - The

temples in this period consists of a Vimāna, and Ardhamaṇḍapa, in a few cases

an entourage of Aṣṭaparivārālayas. The whole complex is surrounded by

the prākāra, with a small Gōpura at the principal entrance. The superstructure

of the gopura, wherever present, is in brick and of later construction, and does

not provide evidence for the development of that structure in the Chola period.

The plan of the vimāna is always based on a square. The vimāna can be laid out

on a straight mānasūtra, or angas can break the plan into karṇas and bhadras. Sometimes,

it is even made more emphatic by the introduction of Sailāntara recesses.

Temple plans

Temple plans

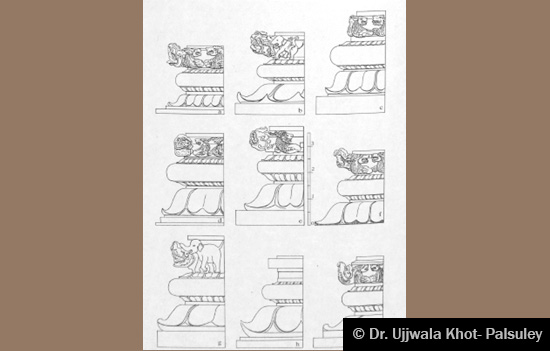

Adhiṣṭhāna-

The original Pādabandha adhiṣṭhāna was used in this period along with the

introduction of the new varieties. In the Pādabandha class, the galapādas in

the kaṇṭha-moulding often carry beautiful reliefs showing episodes from the

Epics, Puranas and other literature.

A second frequently used adhiṣṭhāna is Padamabandha. The Kapotabandha, known during the Pallava times was infrequently used and then revived during Parantaka’s times.

From these types, certain derivatives and composites

also occur - Padmaka, Vaprabandha, Sundarābja and Puṣpabandha, all appear in

varied degrees of preference.

16 An example of

adhisthana, walls and Vimana of early Chola period

Walls -

These usually with a Vēdī. The wall is adorned by pilasters. The

Brahmakānta type is often used alone, but in many instances, one or another of

the other three types also takes part in the rhythm of the wall. Viṣṇukānta and

Īśakānta were frequently used and in a few cases. The split Īśakānta type is

generally used to frame the central dēvakōṣṭha-niches. Mālāsthāna, laśuna, ghaṭa,

maṇḍi and in rare cases, phalaka from sub-parts of these pilasters. These

usually are carved with considerable finesses and elegance, at least in the

early half of this phase. Pōtikās of all three varieties - Taraṅga, Ratna, and Citra-

are found, but compact versions, often without the Taraṅga undulations, are favoured.

The dēvakōṣṭha frequently are crowned by patra-tōraṇas of chitra or ratna type

or by a composite of the two types.

As icons in the dēvakōṣṭha, Dakṣiṇāmūrti (south),

Ardhanārī (west), and Brahmā (north) form the general rule.

The ardhamaṇḍapa walls have often Durgā on the north

and Gaṇēśa on the south. Rarely, Harihara takes the place of Ardhanārī.

In Parantaka’s time and later the latter was frequently replaced by Viṣṇu or by Liṅgōdbhava-Śiva. Bhikṣāṭana and Vīņādhara appear rarely, and then largely as a substitute for Dakṣiṇāmūrti. In the last days of Parantaka or early days of Gaņḍarāditya, Agastya was added to the south wall.

Other divinities found on the ardhamaṇḍapa walls,

particularly in many buildings of Sembiyan Mahadevi, include Nataraja, Bhikṣāṭana,

Ardhanārī, and Gaṅgādhara. Āliṅgana is known from a few examples.

The recesses between bhadra and karṇas were filled by

dēvakōṣṭha (without tōraṇas) or with guhās. These sometimes carry figures of

amaras and apsaras. Sometimes panjara kōṣṭhas decorate these recessions.

The prastara is composed of kapōta (with bhūtamāla

underneath) and prati-kaṇṭha with vyāla-busts.

Vimana - The

Vimana of the temple is generally of Ēkatala type. With a few exceptions,

the grīvā and śikhara are built of brick and are often of a later age.

Sometimes the grīvā is of stone, but the shikhara- built of brick- is a later

reconstruction. These are also Dvitala Vimāna with a full enclosure of

kūṭa, hāra, and śālā elements. The ardhārikā walling of the second storey

supports its prastara, which is topped by grīvā and śikhara.

The kūṭa and nasikosthas of the hāra generally carry

the figures of rishi and Amaras. The sala and griva-kostha

figures are generally in line with, the figures in the dēvakōṣṭha of the first

tala.

The corner of the upper tala supports figures of the

vahana of the main deity. This usually is a nandi since the temple most

often will be Śaivite in this period.

The architectonic of vimāna, both in plan and

elevation, is much improved under Cōl̤as. A ēkatala vimāna in this phase always

has a large rudracchanda (vrtta) śikhara. Dvitala and tritala vimāna

usually favour the brahmacchanda variety. Stupis for both the karna kutas

and the śikhara follow the configuration of the cupola roof; those for the

salas, usually a pair are always found.

The ardhamaṇḍapa walls frequently have Brahmakānta

pilasters. This hall has a flat roof. In the interior, four pillars generally

are used to form the nave, though in halls of similar dimensions, only two are

found. Normally, the Viṣṇukānta type is used. In only a few cases are Īśakānta

and Indrakanta types found. The ekasakha doorframes of the ardhamaṇḍapa and

garbhagriha were only rarely carved.

In a very few cases, a maņḍapa was also introduced a

little distance away from the ardhamaṇḍapa. Later this was connected to the

ardhamaṇḍapa with the help of a grilled antarala-walling.

In the individual components of Padas, a greater

perfection was achieved. builders demonstrated a superior understanding of the

wall rhythms, using architectural devices to relive the relative plainness of

the walls. Haṁsamālā is often found below the prastara of the upper

floors and below the śikharas, the haṁsas in the haṁsamālā are rendered in a

continuous series and in profile.

Carving in this period, especially the early part is

generally very fine.

Conclusion

The early phase of Chola temple architecture showcases refined architectural elements. During this period, Choḷas, based on their interpretations refined Ṣaḍvarga – 6 major divisions of temple elevation, anukāya- component element, and various ideas of decoration.

Keeping the formal arrangement of the temples the same

as the neighbouring architectural styles like Pandya and Pallavas, Choḷas have

improvised on the rendering of elements for example- buildings such as

Airāvātēśwara temple at Kāncī, of early 8th Century and the Tālinatha temple at Tiruputtūr in Pāṇḍināḍu from AD 862. They introduced several types of adhiṣṭhāna- Padamabandha, Vaprabandha, Sundarābja, Śribandha and Puṣpabandha. Kapōtabandha attained a new personality when it was revived by Chola architects in Parantaka’s times. Experiments were made to evolve the variations in older types including the Pādabandha.

Along with the consolidation of power, early Chola

kings, and other royal family members, were keen on developing an exclusive

style of temples. These experiments from the early period are visible from the

temples till the 10th C AD. The perfection in the architectural elements along with the variations and experiments later gave rise to the much larger temples which became the symbol of Chola’s prosperity like Brihadeeshawara Temple at Tanjavur, Gangaikondacholapuram and Airavateshwara Temple at Darashuram.

To read

all articles by author

Also read

1. Album Brihadeesvara Temple, Tanjore

2. Album Gangaikondacholapuram Temple

3. Album Darasuram Temple near Kumbakonam

4. To see all albums of Temple of Tamil Nadu

5. About Chola Kings and Political Organization

6. Inscriptions during Chola era

7. Were Cholas Hindus

8. The inspiring battle of Vijayala Chola