- This is the story of Rao Jodha Desert Rock Park and

how it got started. First they had to clear the area of wild tree of Marwar

called Bavalia.

- Nothing worked. Help came in the form of highly

skilled rock-miners, the Khandwaliyas whose ancestors had chiseled gigantic

blocks of sandstone from the hill to make the Mehrangarh Fort.

- Dhan Singh rang the rock with his hammer at a few more places. The sound the hammer made told him all he wanted to know about the underlying rock.

Roughly six years ago, in the rains of 2005, I was invited by the Mehrangarh Museum Trust to ‘green’ an unruly, rocky wasteland of some 70 hectares adjoining Jodhpur’s medieval Mehrangarh Fort, on top of the hill. It was already green, but it was August and I knew this was a short-lived trick and that as soon as the rains ceased and the moisture fled, the whole tract would quickly return to being bare and rocky. It was a daunting prospect.

The area had suffered decades of disuse and was

severely eroded. It was overrun by a horribly invasive, bullying shrub from

Mexico whose seeds had been scattered over the entire city from an aero plane

nearly a century before. There was hardly any soil and the underlying

crystalline rock, volcanic in origin, was many times harder and more difficult

to work than tractable sandstone.

It didn’t take a genius to see that the only way forward was to draw inspiration from nature and plant the things that grow naturally in rocky parts of the Thar Desert. Of course, we had first to tackle the Mexican invader and grub it out - but that’s a story I’ll come to in a moment.

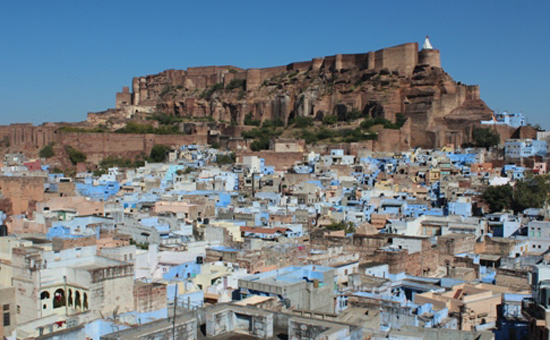

Mehrangarh Fort, rear side view.

Mehrangarh Fort, rear side view.

What we set out to do, in a word, was to try and restore the landscape to a ‘natural state’ with plants native to Marwar’s rocky desert. We didn’t really have any means of knowing what this area looked like before. It was last inhabited five or six centuries before, perhaps even longer. But it was reasonable to assume that it was once like other wild or semi-wild rocky terraces in the desert.

Give or take the presence or absence of a few

pantropical weeds. Using inference and a little intuition, it was possible to

piece together an assemblage of plants that once grew here naturally.

Our ultimate objective was to create a Park that would

be like an outdoor museum of rock-loving plants from this particular part of

the world.

Ultimately we would build walking trails and an Interpretation

Centre for visitors, but all that lay in the future. In the bargain, Mehrangarh

Fort would gain from the aesthetic value of a green space surrounding the Fort

on two sides.

People occasionally ask me why we chose to ‘go native’. It’s quite simple, really.

Native plants, by definition, are pre-adapted to the extremely harsh conditions in our tract. Plants native to Marwar’s desert rock are adapted by a few million years of evolution to eke out a living in hostile, water-deprived niches. They live and prosper in precisely the same soil conditions, partnering with the same micro-organisms, adapting to the water regime, climate and temperature gradients that we had in our Park-to-be.

Rock garden area before we started work.

Rock garden area before we started work.

Scientists call them ‘lithophytes’ - plants specially equipped to grow in rocky conditions. So it made perfect sense that our first aim was to search out and bring back lithophytes from the desert and then try and rehabilitate them. It quickly became clear that what I had to do first was to inventory Marwar’s lithophytes and get to know them as best I could.

Making the inventory itself didn’t turn out to be very difficult. The desert flora is well documented and the doyen of the botany of the Thar Desert was alive and well and living in Jodhpur. When we started out, in 2005, Prof. M.M.Bhandari (‘Doct-saab’) was nearing 80 but still had an infectious enthusiasm and an eagerness to share his knowledge with someone like me. Doct-saab became a crucial ally.

Chhatri, Mandore Fort near Jodhpur.

Chhatri, Mandore Fort near Jodhpur.

Over the next few years, in between the business of

grubbing out the invasive Mexican shrubs and planting new ones in their place,

I seized every opportunity of making short forays into the desert.

Rocky hills and terraces became special targets for exploration. But it’s not possible to shut your eyes to the sandy wastes and dunes in Marwar and with Doct-saab’s help and remote control we explored the sandy desert too.

Doct-saab would sometimes direct our exploration from his home, drawing on memories of trips he had undertaken in the area 30 years previously - “When you find the temple near Barmer, go behind it and start climbing a small hill. Within two-three hundred yards you will start to find some small crucifers. Look carefully. White flowers. Four petals… like this…with a touch of orange in the stem. That’s Farsetia. This is the only place you will find Farsetia in India. Maybe it’s there in Sindh, Pakistan, I don’t know. But go, see if you can find it, then come and tell me.”

Sure enough. Slender Farsetia micrantha, less than knee high, a touch of orange in its stem.

Clinging on, somehow, 30 years later in the pediment of a dry, wasted hill. The

only place in India. Wow!

Group photo with Khandwalias.

Group photo with Khandwalias.

This is the story of Rao Jodha Desert

Rock Park and how we got started. It’s not a boast or an advertisement. I just want to share with you a brief account of how we went about it. I knew of no precedents, no one to turn to for advice. Maybe someone out there would like to restore a plot in the desert? Here’s a precedent.

Grubbing out the Mexican invader (Prosopis juliflora) was objective # 1. In Marwari they call it ‘baavlia’- the mad one.

Probably because it’s crazy enough to seek out such inhospitable places, where it hunkers down and digs itself in. Baavlia seems to require no water or nutrients in the soil. It discourages everything else from growing or prospering nearby by secreting toxic alkaloids in its root-zone. It is madly successful in an unlikely, maverick sort of way and fully deserves its Marwari epithet.

Taking Baavlia out, we knew, was going to be a

struggle. If you cut it at ground level, it sprouts with redoubled vigour.

Digging down and pulling it out mechanically by its roots is difficult and

expensive because of the nature of volcanic rock. Using chemicals to kill it is

not feasible in a place where water runoff is collected and stored. So what to

do?

We received busloads of cockeyed advice. “Cut it less than an inch above ground and cover the stumps with green gobar.” Tried. Didn’t work. “Let goats nibble it - the stems will never resprout.” Goats don’t eat baavlia leaves. Too toxic. “Set fire to the plant on a full-moon night.” Didn’t even bother with that one. (Would you?)

I searched on the net and read about a successful

eradication program in Botswana. The magic formula is that you have to reach

down at least 14 or 15 inches below the level of the soil when you cut baavlia, because it has a subterranean budding zone in its upper roots, from where it re-sprouts. So that settled it – somehow, we just had to find a way to dig baavlia out.

Compressor-driven augers was what we tried first. Much too slow and expensive, and completely impractical because of the extreme hardness of the rock. Someone suggested we should try tiny, minuscule, controlled, charges of dynamite. We were skeptical but tried it anyway and watched in dismay as it shattered the crest of a little rocky knoll. These knolls and hills were an intrinsic part of the historic landscape that we had set out to conserve. Lesson learned. Dynamite just wasn’t the answer.

Help came in the form of highly skilled

rock-miners who call

themselves Khandwalias (after the Marwari word for rock - khanda). Five

centuries before, their ancestors had chiseled gigantic blocks of sandstone

from the hill to make the magnificent Mehrangarh Fort.

Would they be able to handle rhyolite, the volcanic

stone that underlies the sandstone on the hill but is so much harder?

We invited Dhan Singh Khandwalia to show us what he

could do and led him inside the Park. He chose a small baavlia no more than a

foot and a half high. Around it, the rock seemed dourly monolithic with hardly

a crack or faultline that we could see. Dhan Singh chose a really heavy,

short-handled hammer, squatted on his haunches and looked away while he smote

the rock.

I thought he was looking away to shield his eyes from flying fragments of rock, but the hammer blow wasn’t fierce and nothing flew. What he was actually doing was cocking his ear and

listening intently. He rang the rock with his hammer at a few more places. Somehow, the sound the hammer made told him all he wanted to know about the underlying rock. Infra-sound. How it was interbedded. How far the underlying layer ran. Where to go in from, at what angle. And how deep it was likely to yield. He shook his head at me, “Yes, I can go in here… At least two-three feet.”

A Khandwalia at work with hammer.

A Khandwalia at work with hammer.

So we left Dhan Singh there to cut and chisel away. An hour later, he had carved open the root zone, digging down about a foot or so. Some of the baavlia’s roots snaked off into tiny crevices in the rhyolite and two short roots that Dhan Singh had pulled out were

surprisingly two-dimensional, like ribbons. This was part of Baavlia’s arsenal of adaptability. Ribbon-roots for linear crevices. Brilliant!

It had been hard work for Dhan Singh, digging down

just 14 or 15 inches. But I had no doubts any more that he could reach down

deep enough to get below the budding zone and demobilize the baavlia

completely.

According to this report

in HinduBusinessline, “They may not have attended any geology classes nor even been to normal school but are masters at reading the temperament of rocks and boulders. One smack with a hammer and the stones silently reveal their inner secrets. The Khandwaliya combed the 172 acres of the Park to remove hidden roots without damaging the terrain.”

We decided at that moment to hire a platoon of 13

Khandwalias to be our permanent baavlia-removal squad. And pit-makers. Their

job was to go down at least 18 inches

(just to be sure), pull out the baavlia, destroy it and then create pits in the

excavated rock to receive new plants.

Go in as deep as is feasible, three, three and a half feet, we told them. It wasn’t always possible to excavate so much, but we knew that these pits - even the shallow ones - could become receptacles for a whole suite of new plants.

Almost inadvertently, we had arrived at a decision not to create new places to plant in.

Baavlia had already done the hard work and shown us exactly where it was

possible for a plant to establish itself in this difficult terrain. Places with

a modicum of soil. Micro-fissures in the rock that connected to micro-pockets of

buried soil.

Provided we could find a means of selecting appropriate plants for these niches, maybe this was all we needed to do? Follow baavlia’s lead. It turned out to be one of the wisest decisions we made - to place new plants only where baavlia had

been evicted from. No change of land use in our development plans.

I remember standing on a small eminence looking at the

Park three months after starting work. We had succeeded in excavating baavlia

from a little less than a hectare of rocky land. The ground was now deeply

pitted, like a piece of comic-book Swiss cheese. We wanted to try out slightly

different mixes of growing media, so a team of donkeys and their handlers went

back and forth tipping pre-mixed soil from side-hung panniers into new pits. A

few pits were nearly four feet deep. Some were elongated, five or six feet

long, following faults in the rhyolite. Many were less than two feet deep,

where the Khandwalias had come up against more recalcitrant strata of bedrock.

Popular dance of Marwar, Kalbelia.

Popular dance of Marwar, Kalbelia.

At that moment, looking around, it was frightening -

the land looked stripped, violated. We had succeeded it removing the scourge of

baavlia from this little patch.

What if we failed to persuade our new ensemble of plants to take root here? What if our confidence had been entirely misplaced? Would we look back and wish that we hadn’t touched the baavlia in the first place? What if we had removed the only

thing that was capable of growing in that difficult spot?

It took a few months before we started getting

answers. Most of the plants that we put in had been grown from seed and were

still small, at best about 9 or 10 inches high. As grasses and other ephemerals

came up quickly in the wake of that first monsoon, our little nursery-grown

plants all but disappeared from sight.

For the first time in decades, it was no longer open season for goats and cattle and camels that used to enter freely looking for fodder – they had been walled out. The whole tract looked wanly beautiful even as the grasses started turning yellow in late October.

We placed 2,600 plants in old baavlia pits that first

year. We still had no real basis to know if these newly introduced plants would

survive. We would soon find out.

Rao Jodha Park, long shot view.

Rao Jodha Park, long shot view.

There are basically three strategies that plants use to survive severe drought. (Actually there’s more than three – I am simplifying a bit).

Succulence - storing water in tissues (leaf, twig, trunk, roots, anywhere will do) like a cactus does - is a good tactic and is widely used. Reaching moisture deep in the soil by means of enormous, penetrative roots works well too, but you have to be a tree to be able to do this. It’s not so easy being a tree in rocky deserts.

By far the most successful strategy involves crass

opportunism - choosing to live only in the short period when there’s moisture around. This last strategy- life in the fast lane - is used by hundreds of desert plants and by a preponderant number of lithophytes.

Imagine a small, herbaceous plant that does not have

succulent tissues nor the time (read: lifespan) to grow long enough roots.

There is a small window in the year beginning with the first rains in July and lasting till late October or November, when the soil retains a bit of moisture and a small herb might be expected to survive. Just about. What it’s been kitted out to do (evolution, always evolution) is to germinate in the rains, rush through its life-cycle so that it flowers and fruits inside the window of opportunity, dropping its seeds in the ground before dying out. These seeds – typically hard-coated, like a time-capsule - lie dormant in the soil, waiting many months for next season’s rains.

If you think about it, it’s a simple but perfectly adequate stratagem – avoiding

drought, rather than surviving or tolerating it. These plants don’t need specialised tissues or organs. They’re just wily opportunists who live their lives breezily when conditions are good, and skip out as soon as it turns nasty.

Leaving behind little time capsules that will

perpetuate their genes when the rains return next season. A large number of

desert grasses use this stratagem. So do about 200 other species of plants.

Come to think of it, so do many toads and insects and a host of small critters

who are not specially equipped to endure the harshest conditions.

Let’s just call it “Dying

to Live”. It works beautifully, and it was up to us now to learn to accept and celebrate this epiphanic moment in the year when the ephemerals come back to life.

Once we understood this strategy, it became perfectly

clear that we needed to find a way of balancing the perennials that we were

placing in old baavlia pits, with the amazing explosion of seasonal plants that

germinated with the first rains.

The ephemerals could take care of themselves. They were superbly equipped to do so. We needed to keep tabs on our perennials to make sure that we were doing the right thing by them. It was crucial to try and learn what worked and what didn’t.

We painted little flat rocks blue with bright yellow numbers, one for each pit. We recorded vital stats like how deep the pits were, what the site quality was (rocky or with some soil), what exactly was going into the pits by way of soil mixes and species of plant… and so on. And then we held our breath.

By December, we went around and painstakingly recorded how these plants were doing. Some had perished - we needed to know why, though it wasn’t always immediately apparent. ‘Nibbled by hares’ or ‘dug up by wild boar’ was a comment in the notes heet. ‘Not sure why’ also figured. There were lots of question marks.

We got down to analyzing the results using Excel

spreadsheets, which allow you to conveniently lump and sort your data. When we

brought all the kummatth (Acacia senegal) data together, for example, it told us clearly that while most kummatths were doing alright, they weren’t managing at all well in pits less than two feet deep. And that they showed a clear preference for a soil mix with a little less clay than we had initially thought. Lesson learned.

The Excel datasheets were equally eloquent about bordi

(Ziziphus mauritiana) and dhok (Anogeissus pendula) and nearly all of

the other introduced plants. Slowly, over the next two years of continuing to

record pit-data, we learned most of what we needed to about placing our plants

in the right situations. Survival rates improved. We were now choosing to plant

particular species in pits of a certain kind based on what we knew about them.

A large part of the guesswork was being filtered out of the planting scheme.

Flowers, Rao Jodha Park

Flowers, Rao Jodha Park

Rao Jodha Park is now in its sixth year of development. That may sound like a long time but remember that out there, in the desert, time marches to an infinitely slow rhythm. In an average year, we contend with a growing season that is less than eight weeks long. If a small tree puts on five inches of new twiggy growth in a season, that’s a triumphal result!

How long will it take before the Park looks

and feels like a natural rocky landscape with mature plants? Oo, that’s a difficult question. Seven years, I had suggested when we started out, to begin

to see concrete results. Maybe another 10 or 12 before there is a substantial accrual of plant growth and biomass. I really don’t know. This is guesswork, even after so many years of watching it grow.

There are still imponderables.

How will the rains behave in the next few

climate-change years, while some plants are still struggling to find a

foothold?

Will we be able to win the support and

goodwill of the people of Brahmpuri who live right next to the Park ie crucial?

Because they have the capability of undoing years of careful tending.

Will the Park be able to count on

continuity of management and support, all of which comes from the Museum Trust

at the moment?

How will the advent of visitors affect the

Park when the gates open for the first time?

We are getting ready to receive our first

visitors in the rains of 2011 and are still busy refurbishing a 16th

century historic gateway in the City Wall for our Visitors Centre. There will

be Field Guides and Plant Lists. Hopefully, Bird and Insect Lists too, in time.

Reptiles. Amphibians.

We want to start a small shop in the

Visitors Centre that sells things related to plants and to Nature, made

exclusively by people in Jodhpur. Livelihoods.

We want to tell stories. About the desert and lithophytes and strategies that plants use for surviving drought. About the best times to visit the Park and how to get to see what’s really worth seeing. But I must stop. I promised – no advertising.

This article was written in June 2011. The

author has kindly agreed to share it with esamskriti.

To visit Rao Jodha Park website . Pictures 1,3,6 are courtesy Sanjeev Nayyar, others are courtesy Rao Jodha Park. http://www.raojodhapark.com/

Author is

an environmentalist and filmmaker.

Also see

1. Pics of Mehrangarh

Fort

2. Pics of Umaid

Bhawan Palace

3. Pics of Mandore

Fort

4. What

to see in a 10 day holiday in Marwar

5. A

desert that bloomed rock by rock