- Read about the evolution of Mother Goddesses from pre-historic times including thoughts on Tantra and Shakti-worship.

In all ancient cultures

or primitive societies women formed to be the foundation pillars upon whom

rested the important tasks of giving birth and rearing the young, while

teaching them what were seen as social norms, culture-heritage, behavioral

habits, and traditions of those times. The women were seen as life producers

with regenerative capacities, hence her organs that helped in procreation

became the symbols of new life, and motherhood became the core figure in

magico-religious cults of those times.

The Paleolithic female

figures found in abundance from various excavation sites with exaggerated

maternal organs, stand as an evidence, showing the popularity of Mother Goddess

worship in prehistoric times; a practice still popular in India, in a more developed

form of worship of the Sakti or the feminine principle.

A regular supply of food and offspring would have been the most important requisites of the primitive society, thus one can assume that preservation of life would be at the core of any prehistoric religious cult. As a general norm it is seen that the way of life of a group of people tend to define the basic framework for the type of deity and manner of worship in that group. From hunter gatherers, as the primitive society moved towards food production or farming, the regular food (hunted or farmed) acquired a high degree of importance and sacredness, and it was likely that the women’s capability of procreation got associated with the plants and animals that kept the society nourished in ancient times.

Thus, the primitive

mother goddess figures (from Middle and Upper Paleolithic times) that we see

with grossly exaggerated sexual organs, initially would have been part of some

fertility rituals asking for greater production of game and human offspring.

During the Neolithic

times as the society slowly moved towards agriculture, the religious beliefs

started adding agricultural rituals alongside the hunting ones that were

already in practice. The graves found in the upper paleolithic sites across the

world held skeletal remains with bones that were reddened using ochre, along

with food, tools, weapons, and ornaments. Red being the colour of regeneration,

and foetal positions of the skeletons tend to point to a belief that the soul

or body would regenerate (a rudimentary concept of re-birth) and start a new

life again.

However, Neolithic graves

show some changes, and the visibly greater pomp and reverence in laying

down the body under the earth, pointed at a changed belief where the body was

believed to affect the crops that sprung forth from the Mother Earth.

Thus, during the

Neolithic times the Mother Goddess was not just a life creating mother, she was

also the Mother Earth from whom the crops sprung, and who like any other woman

could also be influenced with gifts and entreaties and allow herself to be

controlled through various rituals and rites.

Across all neolithic

cultures spread across Egypt, Mediterranean, Syria, Iran, and parts of SE

Europe, female figurines in bones, stones, or clay have been found that are

said to be the direct descendants of the images of deities created by the older

Mesopotamia, Syrian, and Greek societies.

“The Paleolithic

Era (or Old Stone Age) is a period of prehistory from

about 2.6 million years ago to around 10000 years ago. The Neolithic

Era (or New Stone Age) began around 10,000 BCE and ended between 4500 and 2000 BCE in various parts of the world. In the Paleolithic era, there were more than one human species but only one survived until the Neolithic era. Paleolithic humans lived a nomadic lifestyle in small groups. They used primitive stone tools and their survival depended heavily on their environment and climate. Neolithic humans discovered agriculture and animal husbandry, which allowed them to settle down in one area.” Source

Seated Mother Goddess of Çatal Höyük: the head is a restoration, 6000 BCE- Neolithic era. Museum of Anatolian Civilizations

Seated Mother Goddess of Çatal Höyük: the head is a restoration, 6000 BCE- Neolithic era. Museum of Anatolian Civilizations

This figurine was discovered at the Neolithic site of Çatalhoyuk in Turkey.

This figurine was discovered at the Neolithic site of Çatalhoyuk in Turkey.

More on caption - It was carefully buried beneath a platform in a house, along with a valuable piece of obsidian. Made of marble, it’s nearly 7 inches long. Source

Paleolithic era of the

Old Stone Age is correlated with food gathering or Hunting societies/economy;

while Neolithic era roughly relates to the transition from food gathering

to food producing societies, though the latter has no uniform time frame in

terms of the economy.

This is especially so in

India, hence it is more logical to focus on the

anthropological categorizations, which can be better identified and

recorded from among the different surviving Indian tribes (many of whom were

still following the prehistoric customs until very recently).

From a study of the

existing Indian tribes three main types that had been derived are: hunting-food

gatherers, pastoral, and agricultural.

However, the three are not mutually exclusive, nor do they have any strict

chronological order. So often we find pastoral communities that practice

agriculture along with stock raising, and agricultural communities that indulge

in stock raising along with farming. Regarding the cults and rituals followed

by the food gatherers and agricultural societies, the worship of mother goddess

was at the core of all their magico-religious beliefs.

However, the pastorals

had a very different way of living, and they endured greater hardships in their

daily lives. The pastorals were more dependent on a good leadership to protect

their cattle, and this in turn gave rise to the development of the cult of

heroes and ancestors who were worshiped and highly revered by the members of

this community. Since the pastorals spent a large time under the open skies and

endured the wrath of the nature in form of storms, harsh sun, or heavy rains,

their gods were inevitably connected to the sky in which nature and astral

objects were personified as gods. The Supreme God of the pastorals is thus a

man who leads and protects them, much like the head man of a joint patriarchal

family. On the other hand, agricultural societies who are dependent on the

earth to produce their crops developed the worship of feminine energy and the

cult of Mother Goddesses, which involved rituals related to fertility and

magic.

Mother Goddesses and fertility

The concept of Mother Goddess and associated fertility

rituals is the most primitive and longest surviving religious practices in the

world. The belief that women can multiply crops and fruits because they can

create children out of their bodies was universal across all ancient societies.

Thus, came the belief that what is sown or planted by a pregnant woman will

also grow to bear fruits much like the child in her womb, while a barren woman

will make the fields barren too.

As per the prehistoric thinking, women, who were also the first cultivators, with their child bearing capabilities would create a similar effect on the earth’s vegetative powers leading to good harvests, and thus women were seen as repositories (storeroom) of agricultural magic. In prehistoric era people would apply their own experiences from life to the various things that they saw around them, which is now known as principle of analogy.

Thus, natural productivity was compared to human

procreation capability, and earth mother or the mother goddess was

conceptualized from a human mother. There are innumerable such examples from

old Indian literature. Almost all the Puranas and Smritis (law books for

various sects) have the line Ksetra-bhuta smrta nari vijabutah smrtah

puman, where kshetra (seed-field) refers to woman (woman is mentioned as a

seed field also during the marriage ceremonial rites), and a man is identified

as the seed. This likening of the woman to the field or earth means that the

functions of the two are the same, with the belief that conditions that lead to

a woman becoming fertilised applies also to the Earth. The same belief

continues in the ritual known as ambuvaci (observed on and

from 7th day of the third month of the Hindu calendar). It is believed that

that during the four days of the ritual the Mother Earth also bleeds to prepare

for fertilization. All kinds of agricultural work like ploughing, sowing etc,

are suspended at this time so that Mother Earth can rest during her

menstruation (also refer to the rituals of Kamakhya devi in Assam during ambuvaci).

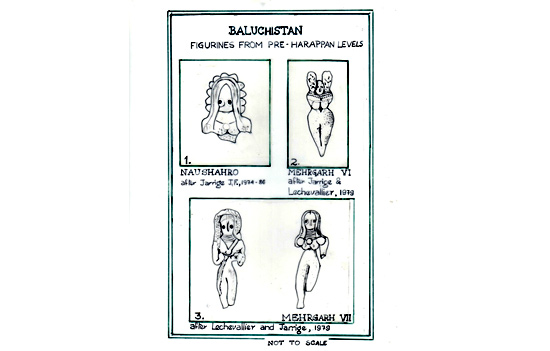

The Zhob and Kulli sites in north and south

Baluchistan have yielded many such terracotta figurines.

The Zhob and Kulli sites in north and south

Baluchistan have yielded many such terracotta figurines.

More

on caption- And these represent the earliest embodiment of the primitive Mother

Goddess figures in the Indian subcontinent. photo Source

The tantric form of worship also lays special

importance to the menstrual blood for the same reason. Here in comes the use of

the color red/vermilion, which we see being used in almost all Indic religious

traditions. The Bhil tribes before sowing

their fields followed the traditions of setting up of a stone smeared with

vermilion. Since vermilion or red colour symbolises the menstrual blood, the

smearing of vermilion implies the passing of the energy of

procreation to the earth and making it fertile.

The Mohenjodaro Mother

Goddesses mostly have a red slip or wash paint over them, as are the Venus

figures of Willendorf (Austria). Briffault who connected the red color with

menstrual blood and fertility further said that in many countries across the

world it was an ancient custom for pregnant or menstruating women to colour

their bodies with red ochre in order to improve their chances of fertility and

also to keep off men during those times. The same tradition is still seen in

Hindu women who wear vermilion (sindoor) after marriage, signalling their

bindings to one man and the readiness to procreate. For the same reason widows

and unmarried girls cannot use sindur, because they cannot procreate. Holi,

which is also a ritual of fertility, originally showed the profusion of colour

red.

The vermilion or sindur on the forehead and hair

parting signals that the woman is married.

The vermilion or sindur on the forehead and hair

parting signals that the woman is married.

In Tantric form of

worship the focus remains on the rituals centering around female genitals (lata

sadhana), and the tantric yantras that symbolise female organs.

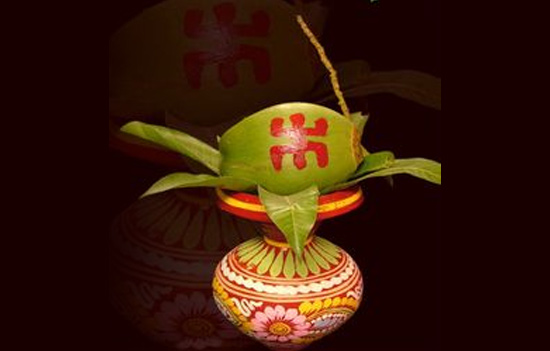

During Durga puja a

yantra known as sarvatobhadramandala symbolising the female

procreation organs is drawn on the ground in the form of alpona. Then a

purnaghata or a purnakumbha symbolizing the womb is placed on it and

sindurputtali or the figure of a baby is drawn on the ghata, and finally

five leaves or amrapallava is placed on the ghata with a sindur smeared coconut

on top. This is thus a simple fertility ritual that connects female

regenerative powers of both humans and plants (human and natural fertility) to

ensure continual procreation.

Purnaghata with the five leaves and coconut on top, denoting a fertility ritual. (pic from internet)

Purnaghata with the five leaves and coconut on top, denoting a fertility ritual. (pic from internet)

That the yantra and

purnaaghata is associated with fertility is best depicted in the murti of

a mother goddess found on the hilly slopes facing the river Krishna in

Nagarjunakonda. It depicts the lower part of a female figure in a sitting or

squatting position with legs doubled up and set wide apart and the feet

facing outwards. The bifurcated part prominently shows the vulva or the yoni-

dvara, and the ornamented broad belt or girdle (mekhala) from below the

naval creates a purna-ghata like imagery. Satapatha Brahmana equates

a purnaghata with the mother goddess; while Kathasaritasagar is

more detailed in its comparison of the purnaghata with that of a womb.

The Mother Goddess from Nagarjunakonda, 3rd c. CE

The Mother Goddess from Nagarjunakonda, 3rd c. CE

Full caption- The Mother Goddess from Nagarjunakonda, 3rd c. CE. “There is a single line Prakrit Inscription in Brahmi characters of third century AD engraved on the narrow strip of space at the bottom of the sculpture (partly covered by the pedestal). It records that the figure was caused to be made by Mahadevi Khamduvula who was an avidhava (whose husband was alive) and a Jivaputa (whose sons were alive) and whose husband is Maharaja Siri Ehuvula Chamtamula. This peculiar iconic form, typical of the Deccan, even in terracotta medium, represents a widely prevalent fertility cult associated with conference of longevity to the lady worshipper’s husband and offspring’s as attested by the inscription too“. Text

and Photo Source

Post Script: the concept and development of Mother Goddess worship across all the ancient civilizations is a long topic and cannot be covered in one such post. I will try to write more on this topic in some of my later posts, and one topic that I particularly wish to take up is the concept of ‘sacred prostitution’ or the ‘devadasi pratha’ that was once a part of this mother goddess worship cult and seen commonly across all the ancient civilizations.

References

1. Agarwala, PK, Goddesses in Ancient India,

1983.

2. Briffault, R. The Mothers, 1952.

3. Bhattacharya S., Tantra Paricaya (Bengali),

1952.

4. Bhattacharya, NN, Indian puberty rites,

1980.

5. Banerjea, Development of hindu iconography

To read all

articles by author

Author studies

life sciences, geography, art and international relationships. She loves

exploring and documenting Indic Heritage. Being a student of history she likes

to study the iconography behind various temple sculptures. She is a well-known columnist

- history and travel writer. Or read here

Article was first published on author’s blog and Here

Article and pictures are courtesy and copyright author.