- Article

comprehensively covers, with pictures, various aspects of jewellery in Indian

Temple Iconography.

Indians,

right from the time they started depicting their gods on seals and murtis,

showed a great deal of love for depicting jewellery on their deities. Almost

all parts of the body from head to ears, nose, neck, chest, lower and upper

arms, fingers, waist, hip, ankle, and feet are shown with different appropriate

ornaments. Grunwedel in his writing “Buddhist Art” noted this, and stated that

“the heroic form of Indian sculptured figures has been and at all times

remained the same- they are decked as for the gala occasions” (p. 31).

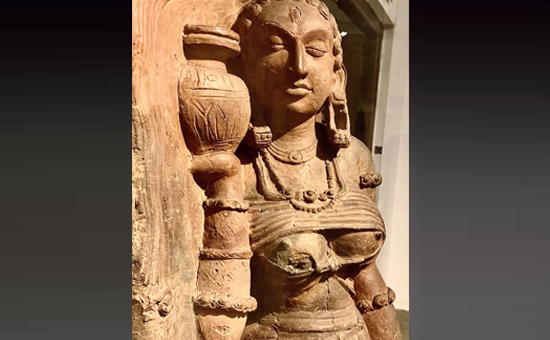

A salabhanjika with long distended ear lobes.

A salabhanjika with long distended ear lobes.

Caption

- A salabhanjika with long distended ear lobes caused owing to constant wearing

of heavy earrings, and this was once considered to be sign of great beauty.

While

Hindu deities were seen in full glory adorned with all kinds of jewellery, the

Buddhists and Jains could not show their spiritual head with ornaments, which

they made up with a greater zeal on the subordinate deities, such

as Bodhisattavas and Sasanadevatas. Only one Bodhisattava (Simhanada Lokesvara - a form

of Avolokitesvara) is nirbhusana,

that is, without jewellery, but this is because of his ideological association

with Shiva, who among the Hindu deities wears the minimum ornaments.

In

the medieval era even Buddha got endowed with a jewelled crown and a torque,

especially in the murtis from Eastern India. Even the murtis of Shiva and

Vishnu in yoga-dhyana postures are depicted with ornaments, perhaps lesser than

the other types, but definitely present. Among the rare exceptions are the two

figures of Nara and Narayana on the side niches of the Deogarh temple, where

they are depicted as two rishis and are devoid of any ornaments. This practice

of depicting even dhyana murtis with ornaments goes long back into the Harappan

culture, where a deity in yogic dhyana posture on a seal (termed as the

proto-Shiva Pashupati) is seen wearing armlets, bracelets, a torque, and a

horned crown.

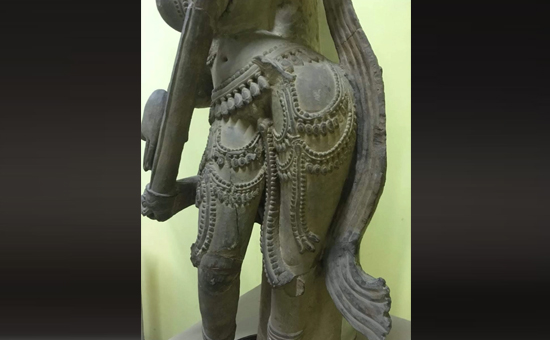

Yoga Narayana in

dhyana posture.

Yoga Narayana in

dhyana posture.

Caption

- Yoga Narayana in dhyana posture, adorned with jewellery, 10th c. CE,

Khajuraho, Chandella period. National Museum, Delhi.

Headgear and Hairstyles

Elaborate

coiffure on a Gupta era head of Devi Parvati, National Museum- Delhi.

Elaborate

coiffure on a Gupta era head of Devi Parvati, National Museum- Delhi.

It

is beyond any doubt that the ornaments shown on the deities were also the ones

worn by the people of those times, thus providing us with a picture of the

socio-cultural lifestyle of the ancient and medieval Indians. As per

the Manasara the different types of headgears are placed under a

category known as mauli, which

are further sub divided into jatamukuta (hairstyle), kirita mukuta (crown), karanda

mukuta (crown), sirastraka

(crown), kuntala (hairstyle), keshabandha (hairstyle), dhammila (hairstyle), and alaka-cudaka (hairstyle).

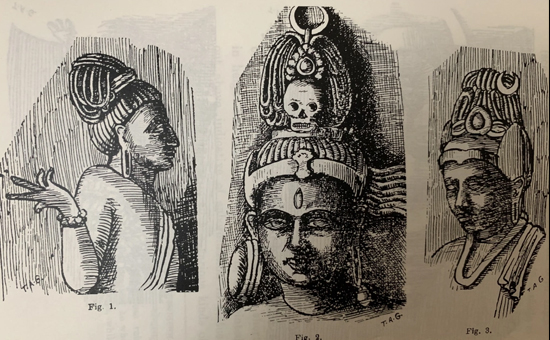

Jatamukuta is seen on the

heads of Brahma and Shiva, and consists of matted hair done up in the form of

long crown at the centre of the head. Sometimes the jatamukuta may be adorned

with jewels; or in case of Shiva, with a moon and a skull. One of the names of

Shiva is Kaparddi, which means

“someone whose matted locks wave spirally upwards like the top of a shell.”

Jatamukuta. (Image from TAG Rao, Elements of Hindu iconography).

Jatamukuta. (Image from TAG Rao, Elements of Hindu iconography).

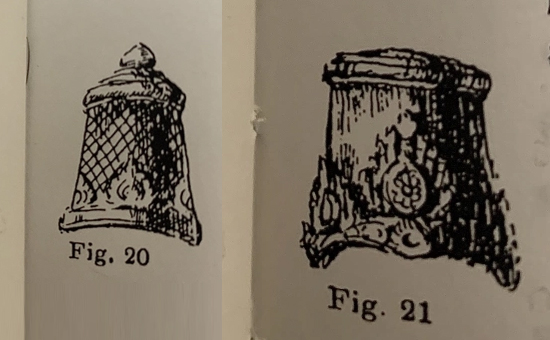

Kiritamukuta,

according to Rao is “is a conical cap sometimes ending in an ornamental top

carrying a central pointed knob, and covered with jewelled discs and bands,”

and is mostly seen on Vishnu, though it can also be worn by Surya and Kubera.

Varahamihira

while describing Vishnu as wearing earrings and a crown/kirita (kundalakiritadhari), says that Surya

should wear a mukuta, and Kubera

should be wearing a crown or a kirita that should slant on the left side of his

head (vama-kirita) (in Brhatsamhita the words kirita,

mukuta, and mauli all have the same meaning, as per Utpala).

Karanda

mukuta is a crown, which is shaped like a karanda or a bowl or a basket with

the narrow end pointing up, and is shorter in size than the kiritamukuta. This

is seen in most of the other deities, and is believed to be denoting a

subordinate position.

Sirastraka is the

elaborate turban that is worn by the Yaksas, Vidyadharas, Nagas (primarily of

the Sunga era), and by generals or parshnikas of the kings. In P.K. Acharya’s

edition of the Manasara it is said that kirita mukuta is to be worn

by a Sarvabhauma, a ruler whose

kingdom extends to the shores of the four oceans; and by an Adhiraja, a king whose control extends over

seven provinces. Karandamukuta is to be worn by a Narendra or a Chakrvartin, i.e. kings who reign over

three provinces (a lesser position than the Sarvabhauma).

Kirita mukuta. (Image from TAG Rao, Elements of Hindu iconography).

Kirita mukuta. (Image from TAG Rao, Elements of Hindu iconography).

Karanda mukuta. (Image from TAG Rao, Elements of Hindu iconography).

Karanda mukuta. (Image from TAG Rao, Elements of Hindu iconography).

Kuntala, keshabandha, dhammila, and alaka-cudaka are

various ways of doing up the hair, and seen on the various devis.

According

to Manasara, the first one (kuntala)

is seen on devi Sri or Lakshmi (Indira), first and second one on devi Saraswati

and devi Savitri (kuntala and kesabandha). The 3rd and 4th styles (dhammila and alaka-cudaka) find no mention in

association with any devis, Instead, Dhammila has

been mentioned as the style to be seen on wives of smaller rulers, such as

Mandalikas; while Alaka-cudaka hairstyle

is to be worn by women who work as torch bearers of the king, and by the wives

of the sword and shield bearers of the king. These hair knots were often tied

together by flowers known as pushpapatta,

or strings of leaves known as patra-patta,

or jewelled bands known as ratna-patta.

Hairstyles of

women (Image from TAG Rao, Elements of Hindu iconography).

Hairstyles of

women (Image from TAG Rao, Elements of Hindu iconography).

In

eastern India, a typical hairstyle has been used to denote Krishna and other

young deities, which has been termed as kakapaksa, a type of hair arrangement on two sides of the head

where the hair is arranged in three tufts with the side tufts fanning out like

the wings of a crow and hanging down to the temples.

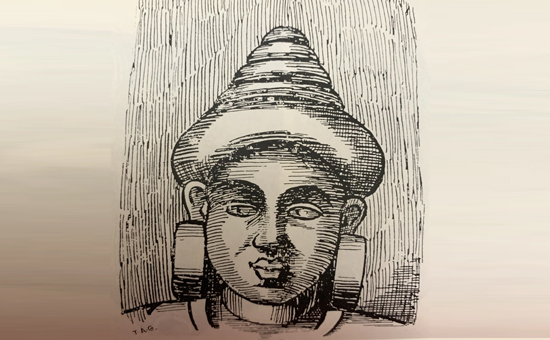

In

Gandhara art different hairstyles are seen on the heads of Avalokitesvara and Maitreya,

where in the former the hair is elegantly arranged upwards with jewelled bands

encircling it, while the latter is with long hair tied sideways in double knot

on the centre of the cranium. In few late Gandhara, Gupta, and post Gupta era

Buddha figures it is seen that his hair is arranged in short separate curls,

and the direction of the curls is from left to right (daksina-vartakesa, which is the sign of a mahapurusa, a mahapurusalaksana).

Avalokitesvara.

Avalokitesvara.

Caption

- Avalokitesvara the hair is elegantly arranged upwards with jewelled bands

encircling it, from Sri Lanka, ca. 750 CE

Earrings

Devi Ganga with large hanging earrings.

Devi Ganga with large hanging earrings.

Caption

- Devi Ganga with large hanging earrings, hair tied in a tight plait, and other

beautiful head accessories, Gupta period, National museum- Delhi.

Piercing

the ear lobes for wearing earrings is a practice followed in India from the

ancient times, and while mostly women are seen wearing it now, earlier they

were worn by both men and women. The ear piercing ceremony or karnavedha is said to be an

important ceremony among the Indics, and the wearing of kundalas was once

considered a privilege for a student initiate (brahmacarin) and a grihastha.

Prthukarnata or long

distended ear lobes caused by wearing heavy earrings was once considered a sign

of beauty and greatness; hence we find Buddha with long distended ear lobes

from different periods and from various parts of India. In fact Agnipurana describes Buddha (Santatman)

as Santatma lambakarnasca

gaurangascambaravrtah, which means Santatma (or he who has a tranquil

soul), is long-eared, fair, and wears garments.

Buddha – Santatma lambakarnasca gauranga, one who is long-eared, and fair.

Buddha – Santatma lambakarnasca gauranga, one who is long-eared, and fair.

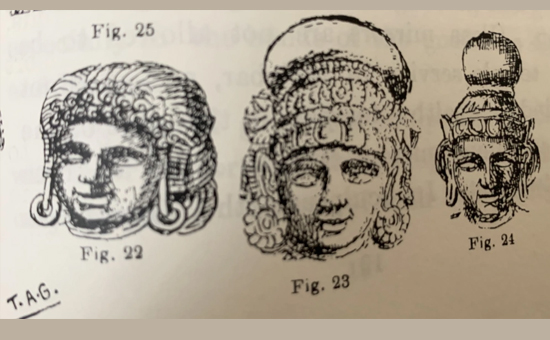

According

to TAG Rao, there are five kinds of earrings: patra-kundala, makara-kundala,

sankha-patra-kundala, ratna-kundala, and sarpa-kundala.

Patra-kundala refers

to cones made of coconut or palm leaves, or gold

leaves. Makara-kundala as the name suggests refers to the mythical

animal makara design of earrings made in wood, metal, or ivory.

Sankha-patra-kundala are earrings made of pieces of

conch-shells, Ratna-kundala are jewel encrusted earrings,

and Sarpa-kundalas were earrings designed in the shape of a cobra and made

of metals, ivory, or wood.

Sarpa-kundalas

are seen on Shiva, and also sometimes on Ganesha. Uma and other devis are often

seen wearing sankhapatra-kundalas,

while makara-kundala, and ratna -kundala can be seen on the

ears of any divinities, both male and female.

Makarakundala (Image from TAG Rao, Elements of Hindu iconography).

Makarakundala (Image from TAG Rao, Elements of Hindu iconography).

Large hoop earrings on a salbhanjika.

Large hoop earrings on a salbhanjika.

Interestingly

the nose ornament termed as vesara

(not a Sanskrit word) is not found in any of the ancient or early medieval

images. It is seen much later in the late medieval images, especially in murtis

of Radha and the gopinis, and this particular ornament is more likely a foreign

import that came in with the invaders.

Necklace

Surya wearing his magnificent hara/necklace, Konark, 13th c. CE

Surya wearing his magnificent hara/necklace, Konark, 13th c. CE

Various

kinds of necklaces form to be an essential part of in the bedecking of the

Indian deities, and some of the more popular necklaces are graiveyaka, hara, niska, etc.

The

earliest type of neck ornament is seen adorning the proto Shiva-Pashupati seal

from Harappa, where concentric rows of neck chains or torques adorn the deity’s

neck. In Rigveda (hymn 33) Rudra is described as adorned with a

beautiful niska, which denotes a

neck ornament, and E. Thomas and D. R. Bhandarkar had suggested in their papers

that it denotes a necklace made of niska coins, where sometimes it meant gold

coins, and in others simply coins.

Hara

also means a necklace or a torque, and there are various types of this ornament

seen on the different deities in ancient and medieval murtis. Surya is

especially known to be depicted with a pralambahari or

a long torque /necklace (Varahamihira); while Shiva is described in

various iconographic texts as being loaded with haras (harabhararpito Harah). Graiveyaka is another type of necklace

which is broad, and is seen on the necks and chests of Yaksas and other deities

of central India.

In

many instances these necklaces have jewel pendants, such as, Vishnu is shown

with the jewel kaustubha mani. The

long garland like necklace hanging from Vishnu’s neck and falling below his

knees, is known as vanamala or vaijayanti, and is five- formed, or made

up of five different types of jewels, such as pearls, rubies, nila, emeralds,

and diamonds.

Vishnu wearing ornaments.

Vishnu wearing ornaments.

Caption

- Vishnu wearing various ornaments and upavita. The vanamala or vaijayanti is

partly broken here.

The

yagnapavita, in medieval era, is also

often depicted as a jewelled one accompanying the cotton one, worn in the upaviti fashion where it encircles the

torso from top of left shoulder and below the right arm. Sometimes the skin of

an antelope (krsnara) is seen

covering a part of the torso and hanging from the shoulder of deities like

Narayana and Nara.

Ornaments on the torso, waist, and ankles

A

popular ornament of the torso known as the channavira, is a form of flat chains over each shoulder in a cross

fashion, where the flat disc lies at the junction of the two chains on the

chest. It is particularly a favourite ornament seen on deities in south India. A

similar form of ornament is also seen in some figures at the Taxila museum, the

Besnagar Yakshini, and on the figure

of a Kulakoka devta in a Bharhut

pillar.

Two

other ornaments seen commonly on the torso of deities are known as udarabandha and kucchabandha. Both are flat bands, where

the latter is used for tying the breasts and holding them in position, and the

former for holding a protruding belly (seen in many Yaksa figures and other

minor deities).

Kucchabandha is seen only in

some female deities, especially when a male god (Vishnu or Subramaniam) is

shown with two consorts, and generally the devi on his right hand side is seen

wearing the kucchabandha.

Devi on right of Vishnu is Sri Devi.

Devi on right of Vishnu is Sri Devi.

Caption

- Devi on right of Vishnu is Sri Devi and she is wearing a kucchabandha (breast

band). On his left is Bhu devi and she is without a breast band. Chola bronze,

British museum.

India, Karnataka, Varuna wearing udarabandha, 1050, at LACMA.

India, Karnataka, Varuna wearing udarabandha, 1050, at LACMA.

Waist

ornaments are of several types and seen on many deities.

The

various jewelled waistbands are known as mekhala (girdle), katibandha,

kancidama (a girdle with small

bells held together by chains). The Surya images are shown with the avyanga (waist

girdle), which has been likely derived from the Avestan sacred woollen thread

girdle worn by Zoroastrians. Ankles are also

shown with ornaments in many figures, wherein anklets in rows are

seen in female figures; and manjira,

an elliptical ornament, is often depicted on both male and female figures.

Waist ornaments.

Waist ornaments.

Surya in his elaborate avyanga (waist girdle), Odisha.

Surya in his elaborate avyanga (waist girdle), Odisha.

Arm ornaments

Earliest

depictions of arm ornaments are seen in the Harappan seal showing the

Shiva-Pashupati from Mohenjo daro. Later the Maurya, Sunga and other dynasty

era images carry on with the trend and depict various types of arm ornaments on

the deities, the names of which are kankana,

valaya, keyura, angada, etc.

Kankana and valaya are worn on the lower arms at the wrist, while the keyura

and angada are worn on the upper arms just above the biceps.

Shiva

is seen wearing a bracelet at his wrist that is known as bhujanga-valaya, which is shaped like a

snake, and is designed as such that at the junction of the tail and the body of

the snake the hood rises. Sometimes armlets had little plaques fitted on them,

as for example, a Bodhisattava in the Mathura museum wears an armlet with a

plaque that shows a human figure riding a bird (peacock or garuda).

Palms

and fingers are also often shown with ornaments comprising of small round discs

held at the centre of the palm with chains crossing at the back, and fingers

are adorned with rings. In West Bengal this ornament is known as Ratanchura and is still popular

during marriages.

Garuda wearing armlets, bracelets, udarabandha, earrings, necklace, and upvita.

Garuda wearing armlets, bracelets, udarabandha, earrings, necklace, and upvita.

Devi Yamuna wearing thick bracelets, armlet, necklaces, and long hanging earrings.

Devi Yamuna wearing thick bracelets, armlet, necklaces, and long hanging earrings.

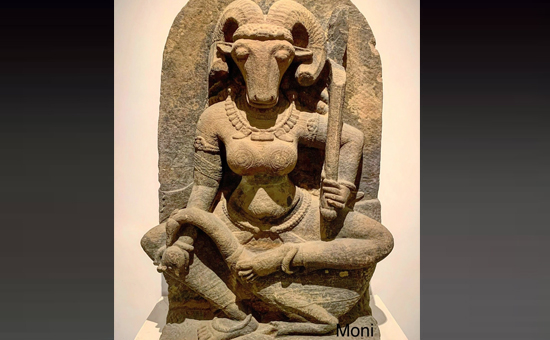

Yogini Vrishnana in her various ornaments.

Yogini Vrishnana in her various ornaments.

Our

deities and our temple art are a documentation of our ancestors and depict

their socio-religious customs, lifestyles, and the general way of living. Thus,

the jewellery that we see on our deities are what the people of those times

wore and what were in fashion; and some of these ornaments and designs,

starting from the Harappan times, still continue, showing the continuity within

our culture; perhaps the longest surviving religion and culture that is still

in practice, beginning from the prehistoric times until date.

References

TAG

Gopinath Rao, Elements of Hindu Iconography

To read all

articles by author

Author

studies life sciences, geography, art and international relationships. She

loves exploring and documenting Indic Heritage. Being a student of history she

likes to study the iconography behind various temple sculptures. She is a

well-known columnist - history and travel writer. Or read here

Article

was first published on author’s blog and here

Article and pictures are courtesy and copyright author.