When we embark on a circumambulation of a temple (pradakshina), our eyes come across many

figures besides those of the gods and the goddesses. Among the ones we most

frequently meet are the chubby ganas

busy blowing into conch shells, or bearing heavy loads of the temple, or

sometimes playing the musical instruments. Others that we cannot miss are the mithuna couples (erotic art), and

beautiful apsaras (celestial

dancers); while the Gandharvas (celestial musicians) and Vidyadharas (celestial figures that dispel ignorance with their

sword of knowledge) make less frequent appearances. Quite often we also notice

the motifs of a hamsa or a swan going

around the temple walls, marching along like soldiers or sometimes even teasing

the round ganas.

As we look at these images repeated in almost all temples,

the figures automatically turn into an integral part of the temple

architecture, embedding themselves deep into our inner consciousness, so we

accept them unquestioningly. Being a part of the temple walls, these figures or

images also acquire a divinity of their own in the mind of a bhakt, as he

or she completes the pradakshina with thoughts focused on the divine presence

inside the garbagriha.

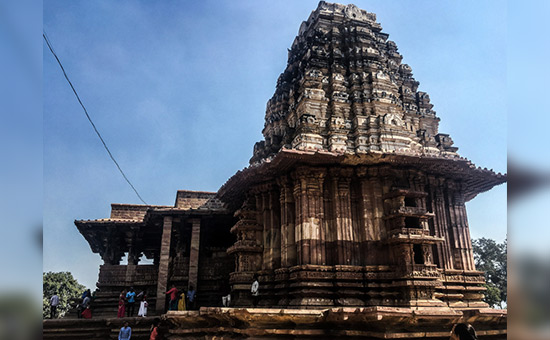

The Ramappa Temple.

The Ramappa Temple.

The Airy Spirits and Breath

Vidyadharas, Gandharvas, Apsaras, Ganas

and Hamsas

According to the rules laid by Shilpa

Shastra, certain murtis have their positions fixed on the temple

walls, spread radially from the main deity stationed inside the garbagriha.

Such murtis can be divided into two categories: the prasar-devtas, which are

the various forms or aspects (rupa) of the main divinity residing inside the

sanctum; and the ashta

dikapalas or gods of the eight cardinal directions, whose

places are fixed in predetermined niches/positions on the temple walls.

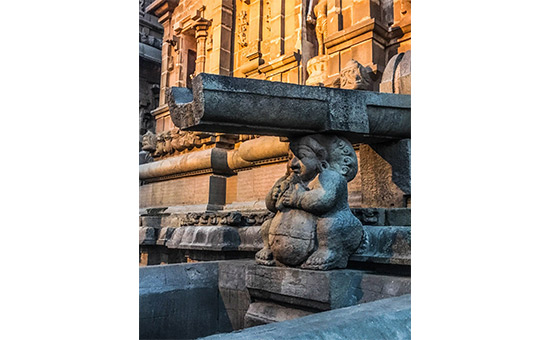

A gana, full of air, blows into a conch shell, producing a sound that is inherent in the air around us (Brihadeswara temple, Tanjore)

A gana, full of air, blows into a conch shell, producing a sound that is inherent in the air around us (Brihadeswara temple, Tanjore)

Between the fixed images there are spread various other

celestial figures, such as the apsaras, gandharvas, etc., and among them the

ones that amuse me the most are the little ganas. The ganas, as

Kramrisch would let us know, are the imagery representations of air, which is

one among the five essential elements that make a human body (panchamahabhutas-

air, water, earth, fire, and ether ); and as we know, it is the air

that summarily supports all our bodily movements.

As India understands better through images, the temple

stapahtis had given a body (an image) to Air and we see that in the form of

ganas, which in a literal sense are mere quantities (gana when

translated denotes a quantity). Shown as potbellied to make them appear full of

air, the little fat airbags or ganas rush around lending a shoulder to a heavy

structure, such as a pillar or the shikhara; or playing musical instruments;

and sometime blowing into the conch-shell.

Airy, full of life, yet in reality body less, the

ganas are also a symbolic representation of the lightness of a mind in full

concentration focused on becoming one with the Brahman or Paramatma.

Apsaras and Gandharvas (Neelkanth

temple. Alwar)

Apsaras and Gandharvas (Neelkanth

temple. Alwar)

The Apsaras, the Gandharvas,

and the Vidyadharas represent airy spirits; their bodies made of airy substances that show the five attributes of air, such as running, jumping, stretching, bending, etc. Thus, we see Apsaras performing the heavenly dances in the city of Amaravati, while Gandharvas playing heavenly music there. The Vidyadharas who are not a part of the musical soirée are often depicted as flying alone, or sometimes with Apsaras. They soar lightly across, carrying the sword of knowledge, which they use to cut through clouds of ignorance.

Despite the inevitable aggression of time or kaal that

destroys everything, the vidyadharas with a determined detachment of mind, keep

pursuing knowledge relentlessly.

Hamaa bird seen on the walls of Sri Someswara temple, Kolunapaka. Photo credit: Zehra C

Hamaa bird seen on the walls of Sri Someswara temple, Kolunapaka. Photo credit: Zehra C

The geese or swans that

we often see marching on temple walls (they are rarely shown in flight)

represent the breathing rhythm; or Ham-Sa; where HA is the sound of breath

going out, and SA is the sound of air entering the body. The control of breath

which is practiced during Pranayama, is an essential part of Yoga sadhana to

attain the final liberation of the soul. According to Garuda Purana, a person

at any time breathing normally is internally chanting the rhythmic mantra of

Ha-M-sa: Ha-M-Sa. This breath, the essential seed of life, the

pran-beeja, finds an imagery manifestation in the form of Ham-Sa. The

Hamsa bird represents the union point of atma with paramatma, towards which fly

all celestial airy spirits, such as the ganas, gandharvas, and the dancers

(apsaras).

Surasundaris are

a representation of the Sakti, or the passive primordial Energy. They form a

part of the ‘avaran devtas,’ and belong to the air-world or

atmosphere. These female figures are a manifestation of the great beauty of the

Devi, who has for a moment has become conscious of her beauty and is sensing a

deep pride in it, while feeling animated by her sudden passion. Hence, she is

charming and alluring, expressing divine vitality.

Various forms of

Sakti include the Apsaras (often also referred to as Suranganas), Yaksis

also known as Salabhanjikas, and Natakas. Representing

vitality and movement, the Apsaras denote atmospheric

movements, while Yakshis/ Salabhanjikas denote

foliage movements, and Natakas are bodily movements shown in

the form of dancers.

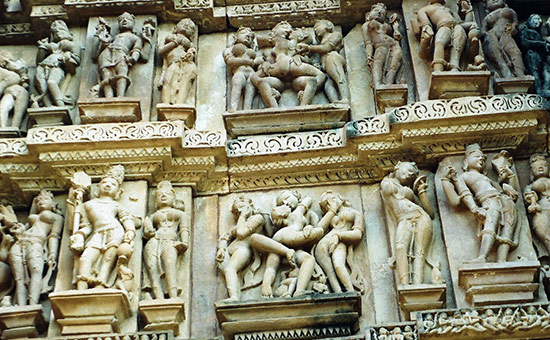

Mithuna couples Khajuraho. Pic by

S Nayyar.

Mithuna couples Khajuraho. Pic by

S Nayyar.

Mithuna

“Embracing Shiva as the Madhava creeper clasps the

young Amra tree with his bosom like cluster of blossoms” – Yogavashishta,

Nirvanaprakarana

Erotica or mithuna couples that we see carved on

temple walls reflect a deeper underlying philosophy than just representing

sensuous earthly pleasures. Deep in the throes of passion the mithuna couples

represent the transition from a physical to the spiritual plane of

consciousness, analogous to the walk from the mandapa to finally meet the

divinity present within the temple embryo or garbhagriha.

In the Vedas, we find the mention of four purusharaths or

human life goals, and one among them is Kama or satisfying

physical pleasure (the other three being Dharma, Artha, and Moksha).

Mithuna sculptures on the temple walls pander to this ancient Hindu philosophy,

which believes that yoga (spiritual exercise) and

bhoga (physical pleasure) are the two paths that lead to

moksha (final liberation).

As Kramrisch explains, when a man is embraced by the

woman he loves he becomes unaware of everything else, inside or outside;

something similar happens when the spiritual being of a person is embraced by

the all-pervading Supreme Soul. In both instances he forgets everything else

that is external or internal to his being. He is satiated, has nothing more to

ask for, and becomes free from all pain, and one experiences unending

happiness, a state of sadaa-sukham.

Thus, mithuna becomes a reflection

of the other purusharath: Moksha, where there is a union of two

inseparable substances, the Purusha (essence or mind) and Prakriti (Sakti or

energy); hence we find Shiva needs Sakti for the final release or moksha,

the ultimate objective of life.

Essentially, the mithuna

couples are thus an imagery representation of that particular moment when

an atma becomes one with the Paramatma, and

enters a state of eternal bliss and ecstasy.

This form of

ritual (used for mastering the third purusharath or kama through bhoga) is

practiced in Tantric worship, and it is for this reason we find gods and

ascetics also shown in mithuna postures in some temples. This form of krida

or lila, however has nothing to do with human copulation that aims at

procreation. The love sport of ascetics, which can be practiced only by

sanyasis (who have already crossed the first two levels of sadhana), with a

woman who willingly gives herself just as a “creeper lovingly embraces a tree.”

This form of lila or krida has no connections to dharma, artha,

or kama, and strictly aims at achieving the fourth

purusharath, moksha. The Avadhuta (one of the highest among

sanyasis in terms of metaphysical realisations, who is above all castes and

social norms) doesn’t need this union with a woman. He is already one with the

Supreme entity: the Brahman.

**There is another perspective or line of thought that

believes the mithuna sculptures on temple walls represent

just what it shows: mithuna; or in other words it just

shows Kama (one among the four purusharths),

and nothing more. A part of the daily life, it represents physical pleasure,

which one must see to overcome earthly temptations before viewing the divinity

present inside the garbagriha or sanctum. Keeping this perspective in mind, I

will say that arguments on this topic can be unending without any convergence

of ideas. Symbolism will perhaps depend to a certain extent on the viewer to

interpret what he sees and what he wants to see.

Speaking for myself, I will side with Kramrisch and

choose to see mithuna sculptures as reflecting the moment of ecstasy, which one

experiences with final liberation or Moksha, when the

antaratma unites with the Paramatma to become one.

The prasara-devtas which are various forms of the main

divinity inside the temple, guide and help us to focus on the Supreme Soul

residing in the sanctum. On the other hand these semi divinities like the

ganas, gandharvas, apsaras, vidyadharas, and the mithuna couples constantly

remind us of our sole objective in life: to become one with the Paramatma and

attain final liberation or moksha.

Thus, from that perspective the temple with all its

sculptures also turns into a point of union of the soul with the Supreme Soul;

an imagery concept or a representation of ecstasy through final liberation or

moksha.

Author studies life sciences, geography, art and international relationships. She

loves exploring and documenting Indic Heritage. Being a student of history she

likes to study the iconography behind various temple sculptures. She is a

well-known columnist - history and travel writer. Or read

here

References

1. Tarun Chopra, 2016. Temples of India. Thompson

Press, Delhi.

2. Stella Kramrisch, 2015. The Hindu temple.

MBP Private Ltd, Delhi.

Article

was first published on author’s blog and here

Article and pictures are courtesy and copyright author.