- A little-known tradition of Hindu temples is maintenance of a natural habitat, a space where elemental devas, the spirits of earth and water, can abide freely.

SEATED BENEATH THE BANYAN TREE, Lord Dakshinamurti (Siva), the immortal, the first Guru, who “breathed out” mantras of the Vedas, silently blends

the presence of nature with the eternal revelation of God.

This article is "Courtesy Hinduism Today magazine, Hawaii".

In Hinduism we honor this concept with many sacred places where we can

see murtis such as Lord Siva, Shakti, Ganesha and Naga (the serpent guardian)

beneath trees. In many cases these statues are situated on a low wall built

around the tree.

Our ancient scriptures, including Vedas and Agamas, affirm

the sacredness of trees and nature; and ayurveda has proven the role of nature

in curing illness. In a world in which nature is recklessly altered and

disturbed by humanity, sacred groves must be protected.

In Hindu culture sacred groves are associated with supernatural entities. As a

rule, the natural vegetation is left uncultivated and undisturbed. Many are

associated with ponds and streams, both natural and man-made.

Such groves are known as kavu in Malayalam, devbhumi in

Hindi, kovil kadu or swamichola in Tamil, devarakadu in

Kannada and devrai in Marathi. The exact number of sacred groves in

India is unknown. The official estimate is 14,000. There are likely many more.

Sacred groves are of three general types: those associated with a temple; independent

groves, with no temple, and groves associated with burial or cremation grounds.

Kavus in Kerala belong to the first two categories.

Kerala, resting in the lap of the Western ghats, is home for 2,000 magnificent

evergreen kavus, many with ponds. The major kavus are dedicated to Lord Siva,

Shakti or Bhagavathy, Sastha (or Ayyapp), and Naga. Others are associated with

spirits of a grandfather, grandmother or some extraordinary personality of the

locality. Almost all kavus honor the presence of Naga God (“Snake God”), Naga Goddess. Their murtis, known as Naga Raja and Naga Yakshiamma, are commonly installed on an open platform.

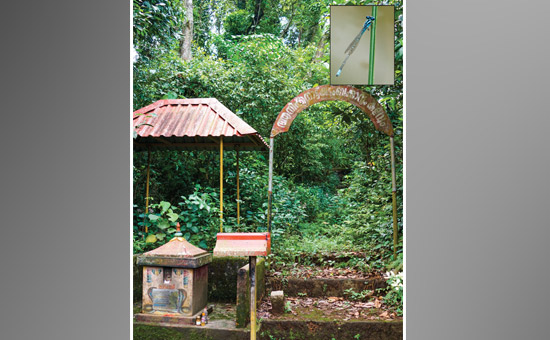

Mannadi Palayakavu

My fascination for kavus began with a visit to the Mannadi Palayakavu Bhagavathi Temple, situated less than two miles from Enathu on the Enathu-Kadambanad road in Southern Kerala’s Pathanamthitta district. The temple is on the right side of the main road; on the left, a narrow road leads to the banks of the River Kallada, perhaps a thousand feet away. On the riverbank is a stone mandapa with a flight of steps down to the river. But the fragile banks and muddy water of the river testified to the extent of soil erosion caused by storms and the deteriorating ecology.

Honoring Gods of the earth.

Honoring Gods of the earth.

Detailed Caption - Entrance to a

family-owned Nagakavu, where a beneficial damselfly (inset) finds habitat free

of human interference.

Coming back from the river, I

found the lush grassy entrance of the temple to be a soothing scene. The main

shrine, to Bhadrakali, the presiding Deity, is enclosed by thick forest - the

kavu - on three sides. To the left of the entrance, the Naga murtis are

installed on an open platform under the thick dark canopy. The murti here is a

naturally emerged stone (svayambhu). The center of the temple roof is open so

as to give the murti direct contact with nature. In front of the shrine is a

small hall on wooden pillars, where traditional rituals are conducted on

special occasions.

The priesthood of this kavu is

chosen from one family, and the current priest is Sri Manoj Narayanan Potti.

According to him, the kavu has been there since time immemorial, and the rituals

are performed according to proper Agamic South Indian tradition.

For Naga murtis, rituals are performed only once a month.

Presently the grove covers

three to four acres, less than half the size it was a few decades ago. Pained

by this encroachment and by the damage done to associated kavus by the

construction of bigger temples, Manoj told me his family and other devotees

have resolved to preserve their kavu and its traditions.

The

Oracle of Mannadi Palayakavi

Until the 19th century, this

temple had the continuous presence of an oracle, or kambithan - a man who “channeled” the devas as their spokesperson. The oracle

was the epitome of spiritual and martial arts

and held the title of a village head. Devotees came to him for advice in

resolving various problems. When a kambithan attained samadhi, his sword and

anklet were thrown into the river in front of the mandapa. Each kambithan,

selected according to merit, and had to recover the sword and anklet from the

river to keep and care for throughout his life.

The Mannadi Palayakavu Bhagavathi temple has an important place in

the history of Kerala. One of the first freedom fighters, the Prime Minister of

the erstwhile Travancore kingdom, came to this temple to seek the help of the

kambithan.

The samadhi of the last kambithan can be seen at the Devaswom board of the nearby temple complex. Devaswom (Sanskrit: “Property of God”) are socio-religious trusts, mostly in Kerala, that comprise members nominated by the government and the community. Kerala’s five Devaswom boards administer around 3,000 temples.

Iringole Kavu

The second-largest kavu in the state is the dense 50-acre Iringole kavu, a famous Shakti

kavu in central Kerala. Situated near Perumbavoor town in Ernakulam district

close to Kochi, the Queen of the Arabian Sea, this serene and calm natural forest

is only about one-half mile from the busy Aluva-Munnar state highway.

The kavu has a Durga temple at its center, but the forest is so thick

that it denies the sight of the temple until we have followed a narrow footpath

about a hundred meters. Here the richness of biodiversity can be heard from the

songs of cicadas and birds and seen in the rich flora and flora. Entering the

temple, we leave the cool, humid, shady natural environment for a brighter and

slightly warmer one.

Uniquely, this temple has only one Deity, Goddess Durga, as a kumari

(virgin youth), exemplifying the austere, serene environment. The Iringole

sanctuary is a full-fledged temple governed by the Travancore Devaswom Board,

which administers around 1,200 temples in the state.

Mannidi Palayakavu

Bhagavathi Temple, surrounded on three sides by thick forest.

Mannidi Palayakavu

Bhagavathi Temple, surrounded on three sides by thick forest.

Sri Gopalakrishna Shenoy, manager of the temple, told HINDUISM TODAY

that as a native of this place, he has noticed that the size of the kavu has

decreased substantially during the past few decades. He stressed the need of

better and concerted efforts to protect the remaining area from further loss.

Privately Owned Kavus

Some kavus are owned by families who are the priests of the kavu’s temples and live in close proximity. In addition to the temple and/or kavu, there is a personal sanctum sanctorum inside the priest’s house where the Naga Gods are worshiped. Entry to this shrine is restricted to family members. Examples can be found at Mannarassala Sree Nagaraja Temple, Vetticode Sree Nagaraja Swamy Temple and Pambummekkattu Mana. (Mana is a Malayalam term for

brahmin family home.)

The first two, located in the Alappula district, have temples and kavus;

the third is in the Thrissur district and has only kavus. These green patches

of divinity are the Naga kavu, where the main Deities are Lord Nagaraja and his

consort Nagayakshi amma. All these divine centers are governed by family-owned

trusts, each with a story of its own.

The Pambummekkattu Mana legend is that long ago, due to intense poverty and

miseries, the head of the mana did penance at the 7th-century Thiruvanchikulam

Mahadeva Temple, one of the Paadal Petra Sthalam, for many years. Lord Vasuki

(Nagaraja) appeared before the brahmin with His consort.

According to the Mannarassala legend, as told by Sri Seshanag of that family,

when one of the early generations was childless, they worshiped Nagaraja, and

were blessed with twin baby boys. One of these was Lord Anantha Naga, who one

day disappeared into the storeroom of the house. That room was converted into a

sanctum sanctorum. Since Lord Anantha Naga was a sibling of one of their

forefathers, they consider Him their grandfather. Today, the oldest woman of the

family represents the great-grandmother who gave birth to Anantha Naga and

performs the main rituals to the God and Goddess.

The eight-acre Mannarassala kavu enshrines the temple of Nagaraja Vasuki

and his consort, with minor shrines for Sri Dharma Sastha and Sri Bhadrakali.

Another portion of the kavu is associated with Anantha Naga, known as Appoopa

(grandfather).

Vetticode is another kavu with a temple for Naga God and

Goddess. Sri Sreenivasan Namboothiri, who is secretary of the temple trust and

a member of the family that owns the temple, told HINDUISM TODAY the system

they follow was devised by Sage Parasurama and refined by Sri Shankaracharya.

According to their system, Lord Ahirbudhanya is one of the many forms of Lord

Rudra. The Nagaraja temple and kavu spreads over six acres.

At Pambumekkatu Mana, the divine center consists of the mana (house) of

the priest family. According to legend, the presence of Nagaraja and His

consort was first experienced in the eastern portion of the old mana. On this

six-acre kavu, the presence of Nagas is readily felt. The secretary of the mana, Sri

Jathavedan Namboothiri, told HINDUISM TODAY the Naga Gods are the owners of the

earth. He told us that non-Hindus, including atheists, also worship Naga Gods.

Certain provisions in scripture allow moving Naga God and Goddess murtis from

their original place in family kavus and relocating them elsewhere. Pressure to

turn old untouched groves to agricultural use, for cattle or to build homes has

resulted in moving some of these Deities. However, there is now a strong

movement among authorities to discourage kavu destruction and displacement.

Many Siva temples in Kerala have kavus on their lands. One of these is

the famous Trichendamangalam Mahadeva temple at Peringanad, near Adoor in

Pathanamtitta district. This temple is managed by a locally elected committee

of devotees. It is a full-fledged Kerala-style temple with a one-acre grove

behind it. The president of the temple, Sri Sreekumar, said the kavu is the

hair of Lord Siva personified.

Oachira Parabrahma is another famous and popular Siva temple in Kerala. Here

Lord Siva is worshiped as Parabrahma in the form of a Sivalingam situated under

a Peepal tree. This temple also has a Naga kavu. The priests here are non-brahmins by

caste. Like the Trichendamangalam Mahadeva Temple, this one is governed by a

locally elected committee of devotees; but unlike other kavu temples, the

management here utilizes the surplus funds for charity.

One of the most famous Nagaraja temples in South India is Kukke Shree

Subrahmanya Temple in Karnataka state. According to legends, puja offerings

made to Lord Subrahmanya are also received by Nagaraja. Lakhs of devotees

throng these kavu temples, especially on special religious occasions.

Deterioration and closing kavus: Mr. Kummanam Rajasekharanbelieves that sacred groves (Kavu)

should be placed the world over.

The banks of the River Kallada at

Mannadi Palayakavu has eroded from storms, and the mandapam on its banks is

deteriorating.

The banks of the River Kallada at

Mannadi Palayakavu has eroded from storms, and the mandapam on its banks is

deteriorating.

Kavus Are a Blessed Resource

To feel the perfect tranquillity, serenity and bliss of Naga kavus, one should visit one of the many big kavus owned by families, where human intervention is absent. People enter the kavu only during the annual puja. On all other days, a traditional oil lamp will be lit at its entrance. In some kavus, family members perform the annual puja, while others hire the services of a priest. Active kavus are seen in almost all Hindu communities and remain an integral part of the culture.

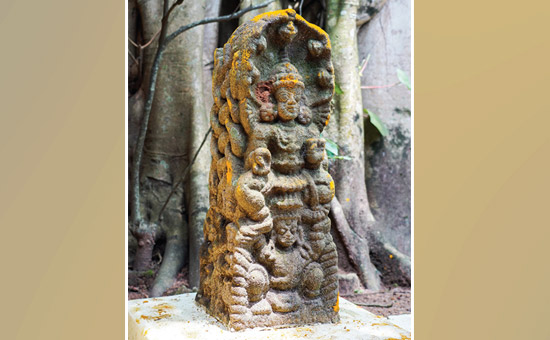

People worship Nagaraja for curing infertility and skin diseases. Kavus are also

part of the agricultural culture with folklore associated with them. Generally,

devotees never harm any living being residing in the kavus; they even leave a

fallen or dead tree to decompose naturally.  A Nagaraja murti that was moved to

Vetticode Kavu from a kavu that was taken over by human habitation.

A Nagaraja murti that was moved to

Vetticode Kavu from a kavu that was taken over by human habitation.

Mr. Kummanam Rajasekharan is an environmentalist who was instrumental in

saving paddy fields in the Aranmula Heritage village from being converted into

an airport. He told HINDUISM TODAY that kavus should be created all over the

world, mainly in urban areas and next to agricultural fields, after proper

studies. In adequate number, these can create a healthy environment which can

provide long-lasting protection for life on Earth.

Even though a new sacred grove can be created without any rituals, simply by

leaving the vegetation uncontrolled on a piece of land of any size, the number

of kavus and the acreage devoted to them is decreasing due to the pressure on

land caused by urbanization, encroachment, unethical socioeconomic attitudes,

and indiscriminate intervention by groups such as atheists and communists.

Still, many kavus have survived the onslaught because of the divine protection

given them by our wise ancestors.

Environmental Benefits

In this world of harsh weather, pollution and rapid urbanization, the environmental benefits of kavus are profound. A kavu and pond are a small-scale forest and natural water body which can protect life on earth in many ways:

1. Maintain the equilibrium of air and food: Humans and animals need food and oxygen and excrete carbon dioxide and water. The plants, algae, etc., in the kavu use carbon dioxide and water and release or produce oxygen and food.

2. Filter and store water, and drastically reduce storm-water runoff: Forests filter and regulate the flow of water. The

litter over the forest floor acts as a sponge which filters, stores and

gradually releases the water to natural channels and ground water. Natural

ponds inside the kavu also store water.

3. Conserve valuable topsoil and reduce soil erosion: A forest is like a protective green cloth over Mother Earth’s fragile body.

4. Conserve biodiversity and balance ecology: In a natural

environment, the populations of species are balanced to an optimum minimum

level. Forests shelter the predators of pests. Snakes in the kavu can regulate

rodent population in nearby agricultural fields. Kavus and ponds shelter

natural enemies of mosquitoes such as backswimmers, dragonflies and their

larvae, damselflies and their larvae, diving beetles, frogs and tadpoles, and

native fishes.

5. Reduce pollution: Plants can remove and/or

phytoremediate pollutants and contaminants from soil and water.

6. Arrest or reverse global warming: Global warming can cause extinction of species, tropical cyclones, extreme weather, tsunamis, abrupt climatic change, sea level rise, increased human stress resulting in violence, etc. These are just a few of its catastrophic effects. Plants can lock CO2 in their bodies to save our planet and the life on it.

The need for nature and kavus was recognized by our ancestors thousands of

years ago, long before the world began facing global warming and ecological

disasters. I remember the words of the renowned physicist Niels Bohr: “I go into the Upanishads to ask questions.” In

these natural habits we find another golden example of the wisdom of the Hindu

sages. My search for answers to certain environmental problems ended in the

kavus.

Author has an MSC and MPhil in Biochemistry and is doing his PhD in Botanical Pesticides.

In Maharashtra Kavus called Devrai. In Rajasthan they are called Oran or Dev Vatika.