-

The 2019 Colonel James Tod Awardee, British Museum’s Dr. Paul Craddock

talks of early metallurgy in Rajasthan – making zinc, and how it influenced

Europe.

At sunset, below

the ramparts of the Udaipur City Palace, the Maharana of Mewar Charitable

Foundation (MMCF) recognised service towards nation-building, art,

conservation, and culture with their 37th annual awards ceremony this weekend.

Along with former ISRO chair Dr. Krishnaswamy Kasturirangan as chief guest, the

MMCF’s chairman, ‘Maharana’ Arvind Singh Mewar, presented the honours.

The foundation

has 13 instituted awards, of which the Colonel James Tod Award recognises a

foreign national’s service or contribution to the country in line with the

“spirit and values” of Mewar.

Dr. Paul T.

Craddock, a scientist attached to the British Museum, was this year’s

recipient. Craddock has been studying early metallurgy in India, esp in the

Zawar region, a mining township about 40 kilometres from Udaipur. Previous

recipients of this award include journalist Sir Mark Tully and author V.S.

Naipaul.

Edited excerpts:

When

did you first hear of Zawar?

It must’ve been

through the 1970s. I wrote my first big paper on brass (the alloy of copper and

zinc) in 1978. By chance, I was introduced in London to a top person from

Hindustan Zinc, and we talked about working together. Our first visit was in

1982, our first excavation in 1983. We came again in the 1990s. In the

meantime, an awful lot of research was done in Zawar and at the British Museum.

Quote from Arthashastra. Credit Dr P.S. Ranawat, Udaipur.

Quote from Arthashastra. Credit Dr P.S. Ranawat, Udaipur.

How

far back were you able to peg mining and smelting work in Zawar?

In the 4th

century BC, Kautilya in the Arthashastra was already writing about how to

establish a mine and mining community in hostile territory. This was around the

time they were developing Agoocha

(about 250 kilometres from Zawar). But then [activity there] crashed. One of my

colleagues noticed small little working in Zawarmala (one of the big mines

about 40 kilometers from Udaipur), which turned out to be from 7th century AD.

Nearby, there

were little heaps also from the same time. That means that either practices

carried on in a very minor scale, or they were restarting traditional processes

then. It gets more interesting because 200-300

years later, they were making zinc. Presumably they looked at the

process of collecting zinc oxide, through these formation of great clouds of

white smoke, and saw most of it going off into the atmosphere.

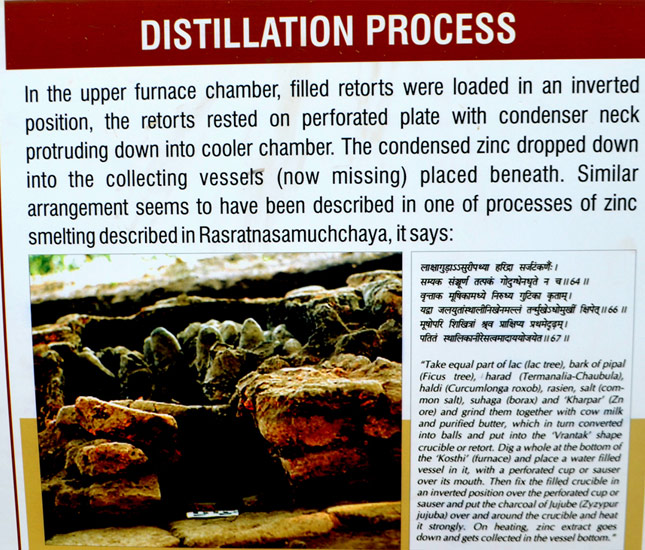

They must’ve

tried to find a better way. I think they then began to take the first retorts

and do it in an enclosed pace, so that you get zinc gas that can’t oxidise, and

then cooled it down in a condenser very quickly, so it drips down to zinc

metal.

It looks like

they were taking a lab technique and slowly developing that into a viable

industrial process. The real beginning of chemical industry. By the time we get

to about a 1000 years ago, we have the first proper industrial unit.

Distillation Process described in Rasratnasamuchchaya. Credit Dr P.S.

Ranawat, Udaipur.

Distillation Process described in Rasratnasamuchchaya. Credit Dr P.S.

Ranawat, Udaipur.

How

was the rest of the world doing making zinc at the time?

There’s Greek

descriptions of collecting zinc oxide. A thousand years later, when the Italian

traveller Marco Polo went to Iran, he observed it there. But nobody got past

the idea of just making zinc oxide. Something

similar [as zinc-making in India] was going on in China, but with a completely

different [distillation] process and technique. They seemed to start

around 1700 AD — meaning another 500 years had gone by.

The

Indian process is based on a local, traditional distillation technology, which

is generally accepted as the first.

They got zinc

oxide, put it in a crucible with copper, and hoped something would come out in

the other end. That was certainly the way that brass was made well into the

19th century in the West.

Some would say

[skip] this distillation processes [as practised in the East], just take the

ore and put it in the copper. But then you’d have no control over the

composition, and all the impurities from the zinc ore will go straight into the

metal!

But the

technology in the West, of making brass from zinc, is well-recorded: It began

in 1738 in Bristol. The process there is exactly

the same as the Zawar process — it looks as though some knowledge of the

Zawar process was obtained. Because it’s like nothing else in Western Europe.

Was

this process in Zawar then all local technology? Or was there any skill

exchange within Central Asia?

Well, the

process really seemed to have developed in Zawar - with the little retorts

first developing into bigger retorts. As far as we know, there was nowhere else

doing this.

Sambholi inscription 464 CE refers to metal industry in Zawar. Credit Dr P.S. Ranawat, Udaipur.

Sambholi inscription 464 CE refers to metal industry in Zawar. Credit Dr P.S. Ranawat, Udaipur.

Do

the people in Zawar have any inherited expertise?

The traditional

zinc smelting process from 1000s of years ago up to the 19th century ended. Partly

because of the Pindari invasions, which really wrecked the place and ended a high-tech

process.

There was also a

terrible famine in 1812, when people left the place.

In the 1850s, there was a colonel, who with the Maharana’s encouragement, tried

to get the processes working again. But that didn’t work out. By the time the

Metal Corporation of India came in, in about 1945, there was nothing. It had to

start all over again.

Given

your roots in an industrial town in England, how important do you think it is

to understand metallurgical practices that existed pre-Industrial Revolution?

Zawar is the

beginning of the Industrial Revolution! European scholars say: ‘The Industrial

Revolution happened in Europe, so it can’t have happened in India’. But the

Industrial Revolution began way back, in countries all over the world, and slowly with international trade in the 17th century,

brought a lot of ideas back to Europe. They then ‘invented’ it themselves.

This is a point

I continually have to make. For example, a very eminent scientist and chemist

based in Sheffield wrote a 3-volume book on crucible steel. Through it all,

there’s not a single mention of India.

And when I put

it to him, he says [about Indian processes] ‘that wasn’t industry! It was very

clever, they made very pretty swords, but it wasn’t industry or science, that

was invented in England!’ That’s just prejudice,

that they couldn’t have done it in India.

The

article was first published here. eSamskriti has

obtained written permission from THE HINDU to share.

Also

read

1

Indian Science

and Technology in the 18th century by Dharampalji

2

Metallurgy of

Ancient Indian Iron & Steel