- This article tells what does Tibetan flag say, significance of stacked stones, Dharma Chakra with deers and why monasteries painted in bright colours. And about Tibetan food.

In the land of lama, don’t be a gamma. A sage advice given by those that build and maintain roads in these cold, barren lands. Whoever has travelled to the distant high mountains of Ladakh and Spiti have seen these cautionary yellow boards with advice written in black by the BRO, asking drivers to be careful.

While being a ‘gamma’ on these rough roads would ensure that the ‘gamma driver’ receives a quick free ride to the land of the dead, the ‘Lama-Land’ by itself is a beautiful and colourful one, with majestic natural landscapes.

Here one cannot miss the innumerable

pretty chortens that dot the landscape; and gaily fluttering flags with their

printed mantras that brighten up houses, farms, mountain passes, and water

bodies.

I had once asked a Ladakhi about the

flags, and was told how the symbolic flags carry powerful mantras that spread

far and wide with the winds, warding off evil. As I stood beside the blue

waters of the Pangong tso listening to him talk on Buddhist philosophies, I

decided to dig deeper once back home and find out more on Tibetan cultural

practices.

Colourful Tibetan flags around Pangong Lake.

Colourful Tibetan flags around Pangong Lake.

Map shows Tibetan Empire.

Map shows Tibetan Empire.

Full caption The mighty

Tibetan empire in the 8th c. CE. Parts of what we now know as Ladakh, Spiti,

North Bengal, Sikkim, and Arunachal Pradesh, were under their control. Hence,

it is not surprising that we find nuances of the Tibetan culture still

running strong in many of these parts. While now, geographically and

politically, Tibetans refer to those from Tibet, culturally many Indians also

practice the Tibetan customs, which is pretty obvious when we travel to the

Himalayan states. Here I will be referring to these common customs as Tibetan

customs, which will include people from Ladakh, Spiti, and other Himalayan states in India. (Photo courtesy: Wikipedia)

What do the flags say?

Hanging long strings of prayer flags/banners, and

hoisting prayer flags on poles is a unique characteristic of Tibetan culture.

These flags are seen almost everywhere in the Himalaya, and each time you see

them, you know Tibetans live somewhere nearby. The gaily coloured flags and

banners are seen fluttering on mountain passes, mountain tops, farms, forests,

beside water-bodies, houses, gompas, and beside roadside chortens and stupas.

In Tibetan language these flags are referred to as dar lcog, wherein dar means cotton

cloth and lcog means an upright position;

thus denoting a cotton cloth put straight up (besides cotton, silk and silk

like synthetic fabrics are also used). This custom has been in practice for

more than a thousand years now, and it is believed that initially the

tradition started as a symbol of war, which later modified itself to denote

religious activities.

As Buddhism took hold among the Tibetans, the

ancient war symbols (flags and spears) slowly turned into philosophical symbols

of positive energy that brought forth good fortune, while removing obstacles

and unhappiness.

A closer look at the flags and

banners show us that there are some fixed colours used here. Five different colours are always used in the same

order: blue on top, followed by white, red, green, and yellow.

The five colours in their proper sequence at

Kunzum la Pass Himachal.

The five colours in their proper sequence at

Kunzum la Pass Himachal.

The five colours used denote

five natural elements that are seen around us. Blue denotes the sky,

white stands for clouds, red is for fire, green is for water and yellow depicts

the earth.

The Tibetan belief is that there must be a balance between these five external natural elements for

prosperity (good crop yield and thriving cattle) and long lives of

people, which in turn will fill the world with happiness and peace. When the

balance is lost, unhappiness and misery will engulf the world.

However, there is another line of Tibetan philosophy that claims the colours represent water (blue), iron (white), fire (red), wood (green), and earth (yellow). In this case the colours should be placed giving precedence to the raiser’s dominating natural element. So if your natural element is water, the blue prayer flag should flutter more abundantly in your house, garden, or farm.

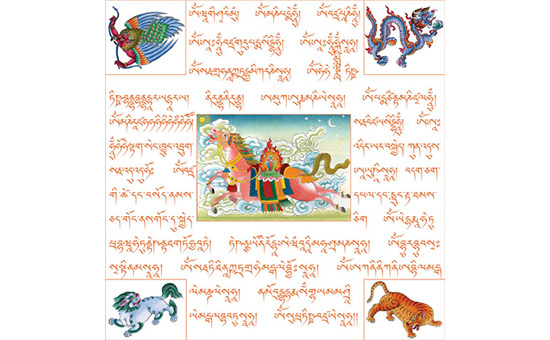

Prayer flags are most often seen with mantras, verses, and different figures printed on them. The most common is the “windhorse” prayer flag that is a symbol of victory. The flag bears a horse (known as klung rta) in the centre and a snow lion, tiger, a dragon, and a garuda in four corners. The flag carries the mantra, “May the horse of good fortune run fast and increase the power of

life, influence, fortune, wealth, health, and so forth.” According to the Tibetan philosophy tiger is the head of all carnivores, snow lion the head of herbivores, garuda the head of bird kingdom, and dragon rules the sky; therefore these are four supreme animals with supreme power to defeat all. The horse at centre represents a journey from evil to goodness, and signifies a positive energy and fulfilment of desires. The name “windhorse” is a recent one(rlung rta is written now instead of the original klung

rta) , and is likely derived from the fact that these flags

are raised high on poles and keep fluttering in the wind.

The “windhorse” flag. The running horse is at the centre and the four supreme animals at each corner. Photo from Wikipedia.

The “windhorse” flag. The running horse is at the centre and the four supreme animals at each corner. Photo from Wikipedia.

Stacked stones.

Stacked stones.

The stacked

stones tell a story too

The stacked stones, which is common

across the land of the lama, tell us tales of previous travellers who have been

to that place. Often stacked stones that are seen on mountain passes are

covered with prayer flags. These cairns are revered objects, as it is believed

they help to please the natural spirits/deities.

These stacked stones/cairns with the prayer flags

are known as la btsas. Here the

word la means mountain pass, and btsas likely refer to a

tax paid when going to a sacred place.

The practice supposedly started long back, when

travellers and traders in the ancient times made arduous journeys across high

altitude passes. Once a pass was reached after a trek that was fraught with

dangers at every step, it was considered a major achievement.

The travellers would then collect stones, make a

stack, and place some food item on it as an offering (this was the tax paid for

partly accomplishing a dangerous job). Besides serving as offerings to create

positive energy, the stacked stones with food items were also offerings for the

later travellers who might arrive exhausted and without any food.

With the passage of time as travelling turned less

arduous, this practice of boosting the morale of later travellers by keeping

food for them gradually went obsolete, and stone stacking turned into a custom of appeasing gods. As more and more stones

piled up, flags were put on them, and slowly they turned into means of

pacifying the natural spirits and gods.

There is another line of thought which

believes that in ancient times the mountain passes were boundaries of different

kingdoms, and as people crossed the borders they were obliged to pay taxes,

which later changed into a custom of appeasing deities.

Dhvaja or victory

banner, on the roof of Sanga Monastery in Lhasa. Photo from Wikipedia

Dhvaja or victory

banner, on the roof of Sanga Monastery in Lhasa. Photo from Wikipedia

The Victory Banner that speaks of defeating four demons

A victory

banner is also found on the roof of Ki monastery in Spiti (Himachal).

The Victory Banner or the dhwaja (in

Tibetan it is known as rygyal mtshan)

is seen on top four corners of shrines,

gompas, and palaces, and are generally made of gold, beaten copper, bronze, or

silk.

The banner signifies Buddha’s victory over the four enemies or Maras (four demons signifying

aggregates, destructive emotions, death, and our desire for pleasure).

Traditionally, the victory banner is a cylindrical

structure mounted upon a wooden pole with silk valances. At the top is a small

white chhatra that is surrounded

by a wish-fulfilling gem. The chhatra is often bordered by makara heads,

and white or yellow scarves are hung from these heads. In the upper part, the

victory banner may show three or nine silk valances denoting protector deity.

Three valances reflect Vaiśravaṇa, who protects the northern parts; while

nine valances

depict the nine auspicious signs.

The victory banners have figures of mythical animals (yalis) that show eagle with the body of a lion, or the head of a fish on an otter’s body. Sometimes a victory banner may have a trident surmounted on black silk, as seen

on the roof of the Potala Palace (photo on side, courtesy Wiki).

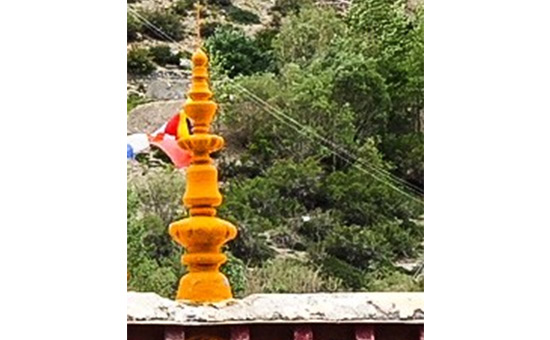

The Golden

Pinnacle.

The Golden

Pinnacle.

The Golden

Pinnacle is actually the Buddha!

The Golden Pinnacle (gan ji ra) as the name suggests is always in

gold or bronze, and is placed on top of

palaces, temples, and gompas. There are five parts, one on top of the other,

and each symbolises Buddha in different forms.

The lowest is a lotus which depicts Amitabha (of

infinite form; The Buddha of Immeasurable Light and Life); over it is

a bell that represents Amogasiddhi (the one that

destroys evil and always protects); next is a wheel symbolising Vairocana (of

the Universe, representing emptiness); fourth is

a vase depicting Akshobhya, the immovable one who

possesses mirror like wisdom and a consciousness of reality that can purify any

negative emotions, like anger; and the last one is

a jewel depicting Ratnasambhava (born of the jewel),

who removes pride and bestows the wisdom of equality.

The Dharma

Chakra with a Deer and a Stag

This is a common sight on the roofs of all

monasteries: the wheel with two deer (one male and one female). It is a

symbolic depiction of attraction of all beings towards the Buddhadhamma.

The wheel represents the Three Higher Training of Buddha, which is the

only supreme path for all to tread. The rim of the wheel is the Buddha

Sutra; the 8 spokes represent Abhidhamma

and knowledge; and the central hub is Vinaya.

The 8

spokes also represent the Noble Eightfold Path and teachings of the

Buddha, while the two deer symbolise knowledge and means to achieve

it. The Noble Eightfold Path is the way that leads to freedom from the

painful cycle of deaths and rebirths.

Do the

Pleated Awnings have any religious significance?

Though there are no recorded explanations, if we go

by what the elderly say, the pretty pleated awnings that we see on doors and

windows are auspicious, and bring in wealth and prosperity. These are

regularly changed during the Tibetan new year (losar), or during any

family weddings, and removed when someone dies in the family.

Seen

on the gateway to the Ki monastery are the eight auspicious signs.

Seen

on the gateway to the Ki monastery are the eight auspicious signs.

The Well

Known Eight Auspicious Signs

Starting from the left pillar down and moving up are:

1. Victory banner

which stands for victory over evil and overall protection

2. The white conch

symbolises beautiful melody of the Buddha dhamma

3. The vase

symbolises knowledge, merit, and fulfilment

4. The

umbrella/chattra/parasol removes the ill effects of ignorance

5. The two fishes

symbolise removal of all imperfections and ensuing prosperity

6. The lotus

symbolises the existence of a person amidst all worldly duties (samsara) but

being devoid of any worldly attachments

7. The endless knot

represents the five wisdom and infinite knowledge

8. The dharma chakra

represents the Three Higher Training.

Monastery in Sikkim. Pic by Suchit Nanda.

Monastery in Sikkim. Pic by Suchit Nanda.

Have you ever wondered why the monastery walls are painted in such bright

colours?

Painting monastery walls in red, yellow, white, and

black is a unique ancient practice, and it symbolises the invoking of deities

associated with rage, control, prosperity, and peace.

The colours are also means of seeking protection of

Manjushri, Vajrapani, and Avalokiteswara, the three great protectors. Red

colour stands for control over the three realms; while white means keeping

diseases at bay and removing hindrances; yellow stands for a long and

prosperous life, and black symbolises removal of all enemies.

Interestingly, before Buddhism made an appearance

in these parts, Bon religion was the ancient religion of the Tibetans. The Bon

religion believed in the worship of natural spirits, and exorcism to

drive away the demons and remove negative effects. Many aspects of the Bon

traditions were absorbed into the Tibetan form of Buddhism, which took a

stronghold in these parts from 7th c. CE onward under the patronage of Tibetan

kings. The Bon religion still survives in some parts of Tibet, and the adherents

follow practices and philosophies that show a striking

similarity to Buddhism.

Dressed salad.

Dressed salad.

Let’s end on a happy note: That’s a wholesome Tibetan meal!

While in land of the lama, eat like the lama. I

always enjoy tasting local cuisine wherever I travel, so the Tibetan local food

was more than welcome when offered. For breakfast I had roasted barley flour (tsampa) with milk and honey, and absolutely loved it. It’s a must try for all cereal lovers.

Culturally, roasted barley flour holds great

significance for the Tibetans, and is held with great reverence. Their most

auspicious dish is Butter Flour or phye

mar, where phye is ground barley and mar is

butter. Butter flour along with roasted wheat are served in two different bowls

as offerings to the deities.

The tradition of offering butter flour to deities goes long back in Tibetan history, and is traced back to periods earlier than 6th c. CE. It is connected with the ancient Bon religious practices, when the communities led a nomadic life and relied on their agricultural outputs for food. Roasted barley signifies the agricultural output, while butter is the essential product of all nomadic lives. The ancient Bon offerings still continue, showing the Tibetan community’s historical roots in agriculture and nomadic life.

For dinner we were served a series of rather delicious

fare:

Few words at the end….

The Tibetans inhabit a land that is barren and

extremely harsh to live in. Yet their cultural practices and traditions are

full of colours, almost as if to balance the bleakness of the landscape that

surrounds them.

The beauty of Tibetan traditions lie in the unique

combination of the ancient Bon religion and Buddhism, and the seamless

amalgamation that keeps both the religions alive and in perfect harmony.

The cultural practices that I have touched upon are the ones that we notice commonly while travelling, and is just the tip of the iceberg. Beyond the tip there’s a world out there of unique cultural practices and traditions that are as colourful and complex as one can imagine.

Tibetans are among the most peaceful

and kind communities that exist in the current scenario; yet such a unique and

colourful culture today faces the risk of losing their very identity and

perhaps even going extinct under various sociological pressures and challenges.

Therefore, it is now essential for

the people who travel to these places to start acknowledging the uniqueness of

this rather gentle and peace loving community, and to help them in maintaining

their distinct identity, without imposing anything external.

As we love the Himalaya more and explore it deeper, it’s also now our responsibility to respect and help preserve the uniqueness of each of community that inhabit the nooks and corners of these sacred mountains.

Lantsa script on Mani stones. It’s an Indian Buddhist script, likely of late Pala origin, hence Bengalis often find some alphabets similar.

Lantsa script on Mani stones. It’s an Indian Buddhist script, likely of late Pala origin, hence Bengalis often find some alphabets similar.

Some books that help to understand the

Tibetan culture better:

1. My Third Expedition to Tibet by Rahul Sankrityayan (Author), Sonam

Gyatso (Translator)

2. Tibet: An Inner journey by Matthieu Ricard (2012)

Sources of Tibetan Tradition by Schaeffer, Tuttle, and Kapstein (2013)

3. The Red Annals by Kunga Dorjee is a history book written in 1346 and discusses

the Bon traditions in details.

To read all articles by author

Author studies

life sciences, geography, art and international relationships. She loves

exploring and documenting Indic Heritage. Being a student of history she likes

to study the iconography behind various temple sculptures. She is a well-known columnist

- history and travel writer. Or read here

Article was first published on author’s blog and here

Article and pictures are courtesy and copyright author.